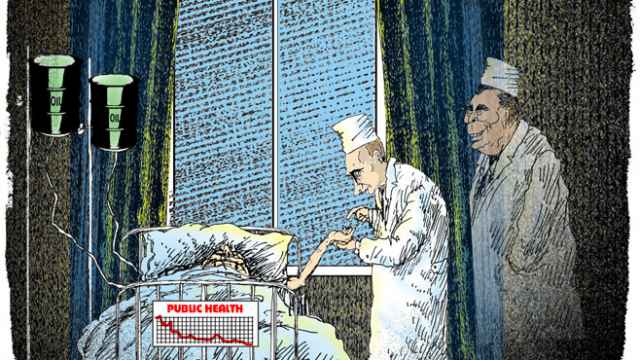

Back in May, it seemed as if the worst was over for Russia. Oil was cautiously rebounding into the $70 a barrel range, the economy (although clearly shrinking) was faring modestly better than expectations, inflation (although high) was starting to moderate, and the ruble had recovered a good deal of its earlier losses against the dollar, and the Central Bank was confident enough in the economy's prospects to begin gradually ratcheting down its emergency rate increase.

Yes, quite a lot of economic and financial damage had already been done, popular living standards were strongly impacted by the ruble crisis and the subsequent spike in inflation and the banking sector was being held together with bubblegum and duct-tape, but a plausible narrative could be constructed in which Russia had gone toe-to-toe with the West and emerged a bit scuffed but basically intact.

Now, however, it is obvious for all to see that Russia is in for a much rougher ride than initially expected. Pretty much all of the trends that, in the spring, served as the basis of cautious optimism have reversed. Even after a modest rally earlier this week, the price of Brent crude sits around $50 a barrel, substantially lower than it was just a few months ago. Persistent oversupply makes any short-term rally an unlikely prospect.

The ruble, too, has fared quite poorly: over the past three months it has lost about 20 percent of its value against the dollar, and as recently as last week was flirting with all-time lows. Considering what is expected to happen with oil prices, a ruble rally also seems, if not impossible, highly unlikely. This makes another spike in inflation, and the attendant decline in living standards, essentially inevitable.

Russia's recession, then, will be sharper, longer, and more painful than initially anticipated. And it's not just because of the "meddlesome" West or its financial sanctions. Russia is squarely in the crosshairs of some ongoing changes in the world economy, changes that are going to make the next few years a lot more challenging than the past few.

During the early and mid 2000's Russia was buoyed by seemingly insatiable Chinese demand for raw materials. Prices for a wide range of commodities hit historic highs and Russia, as the world's largest commodity exporter, benefited enormously.

Now, however, that story is also being turned on its head. The headlines now are not about a China that is surging to world dominance but about a China with a scary debt overhang, a stock-market bubble, and a real economy that is growing at its slowest rate in over 30 years. Ever since the standoff over Ukraine escalated last year, Russia has quite consciously decided to cast its lot with China. That now appears to have been a much riskier decision than anyone expected at the time.

As is becoming increasingly clear, Russia needs to be prepared to deal with a new normal in which the conditions of the world economy, broadly considered, are a hindrance and not a help. For at least the next several years Russia will not be able to count on any positive "headwinds" from the rest of the globe: if it wants to grow, it's going to have to work for it.

If the Russian authorities have a plan for dealing with this new reality, aside from allowing the ruble to freely float, they've kept uncharacteristically mum. Oh yes there's been lots of talk about "import substitution" but it's been just that: talk.

There's been no progress of any kind in changing the regulatory and business climate to promote investment, and there's been no substantive progress in developing transport infrastructure to reduce Russia's (notoriously high) transportation costs. There's just a hand-wave about "domestic producers" and some vague gestures toward the patriotism of Russian consumers. First-year MBA students have produced more coherent strategies.

This is the point at which most Western commentators will go off on an extended rant about Russians' supposedly innate insouciance, passivity, or stupidity, drawing liberally on history to argue that the country has some kind of fatal flaw within its collective DNA.

This doesn't seem to be a terribly effective tactic, as it inevitably degenerates into an orgy of whataboutism and pop history. People, understandably, tend to get a bit defensive

So, rather than proscribe what Russians should think or how they should think it, I will simply note that Russia currently faces a choice about what type of country it wants to be. It can be a place with an integrated, open, and transparent economy, an economy that trades extensively with countries near and far and that is open to and accepting of foreign investment. Or it can be a place that focuses on military "glory" and on the protection of "the Russian world" from the forces of darkness.

These are very different and mutually exclusive trajectories. A country obsessed with the protection of its ethnic brethren is unlikely to be very economically dynamic, and a country with an open, liberal economy is unlikely to be overly concerned with hunting imaginary "Nazis."

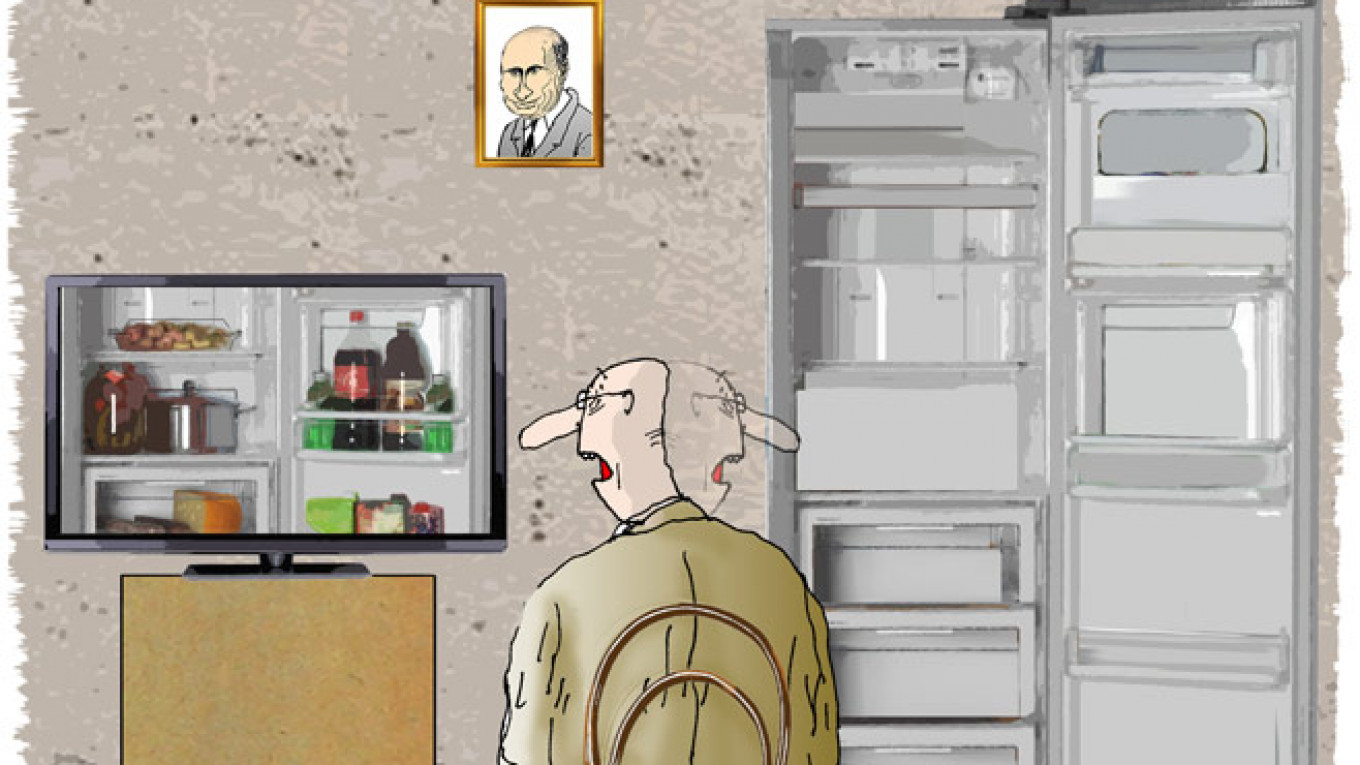

Given the choice between the refrigerator (consumer goods) and the television (patriotic propaganda) I certainly know which one I would choose. Russians need to choose for themselves, but if they vote for the television (as polls strongly suggest they would!) they should be aware of the costs.

Mark Adomanis is an MA/MBA candidate at the University of Pennsylvania's Lauder Institute.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.