The Russian justice system was in rare form this week. On one and the same day, Aug. 24, Russian courts granted an early release to former Defense Ministry property manager Yevgenia Vasilyeva — who had been serving five years in custody for misappropriating 3 billion rubles in state funds — and also sentenced Ukrainians Oleg Sentsov and Alexander Kolchenko to 20 years and 10 years respectively for allegedly forming a terrorist organization and planning terrorist attacks.

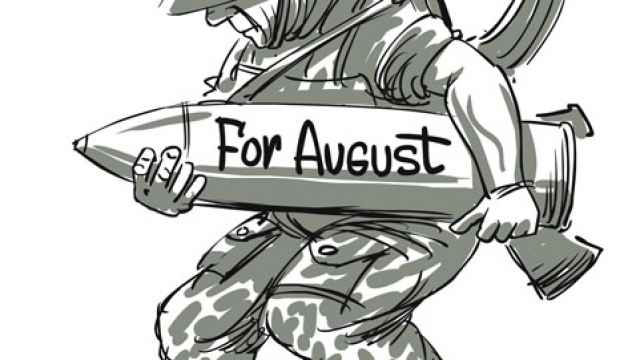

Prior to the trial, the 39-year-old Sentsov had gained prominence as a film director who had garnered awards from international film festivals, including several in Russia. On May 11, 2014, he was detained in Simferopol during a protest against Russia's annexation of Crimea. Almost immediately, Sentsov and several other suspects were transferred to the Federal Security Service detention facility in Moscow.

On May 30, the Russian authorities charged the filmmaker and several of his associates with planning terrorist attacks in Crimea. On June 6, 2014, the authorities denied Sentsov the right to meet with the Ukrainian consul on the grounds that Russia regards those holding dual Russian-Ukrainian citizenship as only Russians. Two other detainees in the case cut deals with investigators and received seven years in prison. Sentsov and Kolchenko pleaded not guilty and received a combined 30 years imprisonment in a penal colony.

When he finishes serving his 20-year sentence, Sentsov will have spent one-third of his life in prison.

I have no way of knowing whether the chargers against Sentsov were groundless, but I do know from my Soviet schooling that it is noble to fight for the freedom of one's occupied homeland. Sentsov was born in Crimea and might very well see Russia as just such an occupier.

No matter how few people in Russia share his point of view, the judges in this case might have taken a moment to consider how this country's actions appear to Sentsov and others in his position.

Perhaps the court held so much damning evidence against Sentsov that even any patriotic motives on his part would not have outweighed the court's verdict and its need to uphold Russia's national security interests.

The conviction "My country, right or wrong!" often leads people to condone the very terrorism that they would otherwise condemn. The assassination of Reinhard Heydrich in Prague in 1942 was unequivocally a terrorist attack according to German law of the time. However, the terrorists consider those who shot the residents of Lidice and sent them to concentration camps, and those who killed Heydrich as heroes of the resistance.

If you had said that to the Germans who were planning retaliatory action in Lidice after Heydrich's assassination, they would have called you crazy and made you regret your words. They also would have reminded you that the Sudetenland was German land and that Czechoslovakia did not even exist before 1918.

I do not mean to compare, but when the huge machinery of Russia's public prosecution takes aim at a film director, there is little chance that the trial will end with his acquittal.

The current Russian authorities have the same Soviet school background as I have, and so they can also reflect on these questions — if they so choose, of course. Sometimes the desire to carry out orders or contribute to the sacred cause of national security eclipses the desire to reflect.

Twenty years is a long time. The judge handing down such a sentence must have done the math and understood that Sentsov, who has already spent a year behind bars, would only walk free in 2034 at the age of 59.

Will the government that the judge supposedly defended by making that ruling still be in power, or will another have taken its place? To sentence a man to 20 years, the judge must have been positive that everything would be exactly the same two decades from now. In any case, he must have been very confident to sentence Sentsov to 20 years before hurrying home to buy imported detergent before that is also banned by another Russian counter-sanction.

This leads to the question of the court ruling granting parole to Yevgenia Vasilyeva. As with the Sentsov case, the public knows precious little about the evidence involved. It knows only that the authorities trumpeted the case on national television and newspapers as an example of their uncompromising struggle against corruption.

For months, the authorities claimed they would stop corrupt officials in their tracks, regardless of their seniority or standing — and that charade continued right up until someone spotted Vasilyeva in Moscow when she was supposedly serving time in a penal colony.

The corruption case against former Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov was politically motivated right from the start. In order to gloat over or, to the contrary, feel indignant over Vasilyeva's judicial misadventures, it is first necessary to get a clear understanding of what Serdyukov did at his post.

If the army was falling apart and Serdyukov was caught pocketing taxpayer money, then he and Vasilyeva should have been questioned as key suspects, and not only as witnesses. But if Serdyukov actually succeeded in strengthening the army and made tremendous efforts to stop the defense industry from milking government coffers in order to produce lower quality equipment at higher than ever prices, then it begins to resemble the situation with Heydrich and Lidice in which the criminals are actually heroes, and vice versa.

It is possible that someone managed to gain the ear of a senior official and convince them of this second version of the story. At that point, the official vice immediately relaxed its grip and Vasilyeva walked free.

However, she was not acquitted — simply released on parole. That is, the ruling was not reversed. Technically, she is still guilty, but for some reason the authorities decided that she need not go to jail. The Russian courts regularly refuse parole to hundreds of petitioners who are incarcerated for crimes far less serious than charges of bilking the government out of 3 billion rubles ($43.2 million).

However, Vasilyeva's appeal was instantly approved. And that is only because the people who feel that Serdyukov's military reforms were beneficial still have some influence at the top. Or else it is because the authorities no longer knew how to deal with the endless scandals over whether Vasilyeva was still in jail or not. She was simply released without any particular reason or justification. In the end, the authorities' impressive story about how they were bringing corrupt officials to justice regardless of rank simply fizzled out.

Vasilyeva's release communicates deep contempt for the Russian people — for all those citizens who demonstrated indomitable will in vanquishing high-handed officials and for the courts and investigators whose work was essentially washed down the drain, regardless of how well it was performed. At the same time, it demonstrated a clear arrogance on the part of leaders who effectively said, "If we want to imprison someone, we will, and if we want to pardon them, we can do that, too."

However, people do not like it when the authorities openly despise them. Although the Russian government does everything possible to demonstrate its contempt for the people, and although citizens display an almost limitless ability to endure such treatment, one day they will simply refuse to respond when leaders appeal to them for help.

One evening, some Kremlin functionary will bring the usual report showing the president's record-high ratings — roughly equal to the value of the ruble against the dollar. But the next morning, they will find masses of people lined up at exchange points to convert their nearly worthless rubles into dollars and euros. And among them might be the same judge who sentenced Sentsov to 20 years behind bars.

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 15 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.