Why hasn't President Vladimir Putin shut down Ekho Moskvy, often described as the "last bastion of free media in Russia?" And more importantly, will he do it?

The riddle of Ekho Moskvy is all the more interesting because the Kremlin has recently moved against other independent media. Last year, for example, it blocked access in Russia to four prominent websites: Yezhednevny Zhurnal (Ej.ru), Grani.ru, Kasparov.ru, and Alexei Navalny's blog. These sites were completely oppositional, never provided a platform for pro-Kremlin content and therefore were useless to the authorities.

In contrast, the Kremlin hopes to use Ekho Moskvy for its own purposes. Ekho Moskvy is known as a radio station, but it also has an important website that attracts a large audience. It is a unique media outlet in Russia in the sense that it claims it does not pursue a political platform. Instead, it gives space to a wide spectrum of opinions.

For example, it offers its listeners and readers the views of liberal opposition members, like Vladimir Ryzhkov and Mikhail Kasyanov, as well as the ultra-nationalist Alexander Prokhanov and the neo-Bolshevik Eduard Limonov. Its contributors range from pro-Kremlin spokesmen to its most ardent critics.

Ekho Moskvy has agreements with VIP commentators, which allows it to repost comments from websites of such opposition activists as writer Viktor Shenderovich and Boris Nemtsov, who visited the station the day of his assassination earlier this year.

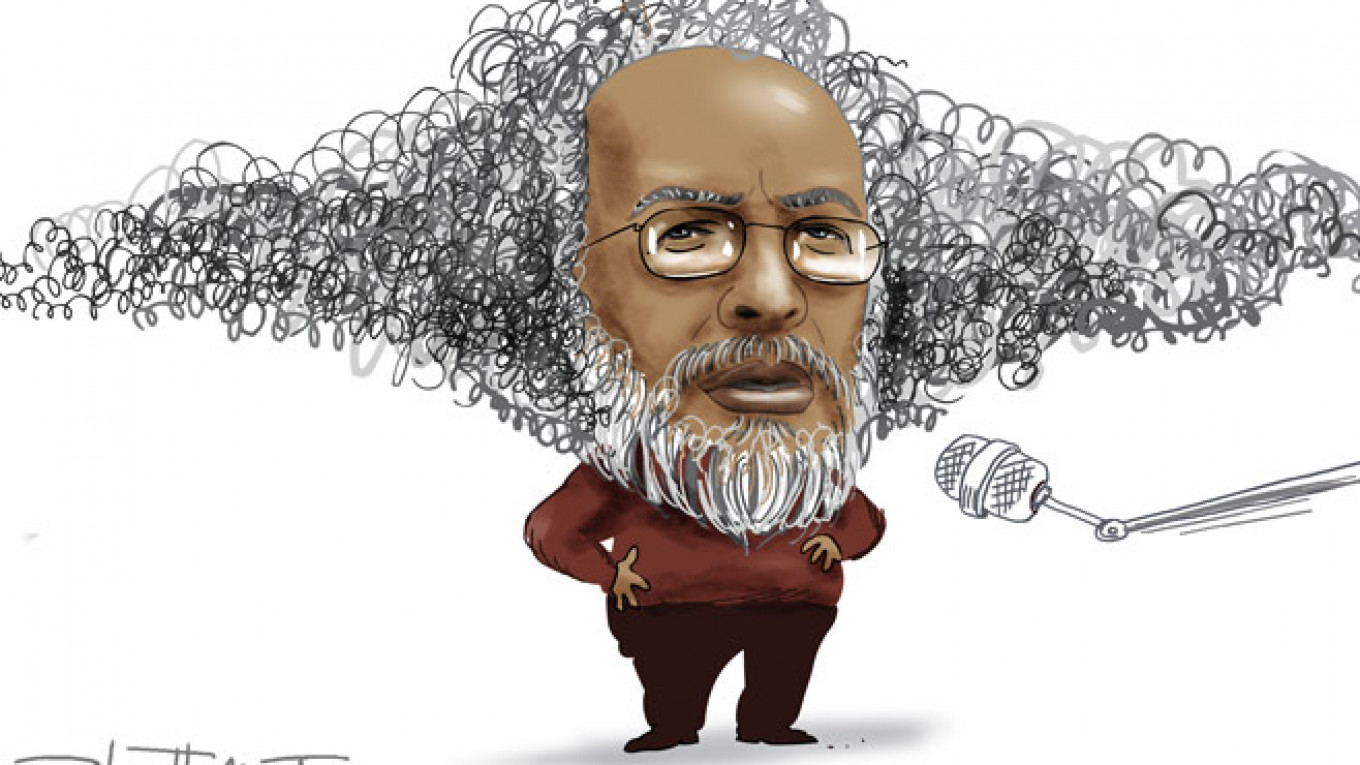

Ekho Moskvy editor-in-chief Alexei Venediktov has a relationship with Putin, who describes him as an enemy who must be opposed rather than a traitor who should be crushed. Does Putin need Ekho for additional sources of information? Probably not.

Putin famously told Venediktov that once he listened to his radio station and characterized what he heard as pouring diarrhea on him. Apparently, the president does not value the information from Ekho Moskvy as much as what he receives from other sources.

Nevertheless, Putin needs Ekho Moskvy for several purposes. First, to show the world that the Russian president allows free media to exist. Second, to demonstrate that he is not afraid of criticism. And, third, as with RT, the Russian propaganda agent aimed at foreign countries, the authorities want to compete and spread their influence even among the "enemy's" audience.

This competition creates problems when those who are criticized take action against Ekho Moskvy. Last year, the Kremlin, working through Gazprom, replaced the station's director, Yury Fedutinov, who had been a close Venediktov ally. The Kremlin has used similar techniques against other independent-minded outlets like RIA Novosti and Kommersant, forcing them to change their editorial lines. Despite the pressure, however, Ekho Moskvy was able to maintain its policies.

Other officials seek to influence Ekho through different techniques. For example, Gazprom Media head Mikhail Lesin demanded the removal of the journalist Alexander Plyushchev. In the case of Plyushchev, Venediktov defended his journalist by temporarily taking him off the air, but then reinstating him.

Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov has publicly announced that he considers Venediktov a personal enemy. In the face of physical threats, Venediktov maintains bodyguards. Similar pressures are not unique to Ekho Moskvy; sadly, they are common for the Russian political landscape.

Uniquely, Ekho Moskvy experiences pressure from the other side as well, as when liberal commentators boycotted contributing to the site. Several authors, including prominent writer Boris Akunin and former Ekho Moskvy editor Sergei Korzun, left the station after Venediktov backed up one of his deputies, who personally insulted members of the liberal opposition.

To be fair, Venediktov has a clearly articulated policy of defending his journalists from the authorities and the liberal opposition. In fact, it is common to hear accusations of bias from both sides. When Venediktov was in Washington recently, we had a chance to ask him about this episode, and he told us that he had reached out to each of the boycotters personally and persuaded some of them to return as contributors.

Unlike most other independent outlets, Ekho Moskvy has a large audience. About 4 million listeners tune into the radio station daily, according TNS Global, and the site attracts more than three million readers a month, which is about 9 percent of Internet users in Russia.

Though Ekho Moskvy is not formally part of the Kremlin propaganda machine, it provides the authorities opportunities to win the hearts and minds of a critical audience. It is important for the Kremlin to use this platform to reach out to the minority of the population that does not claim to support Putin in public opinion polls. Accordingly, media that provide a range of opinions do not threaten the existence of the current regime.

Because the Kremlin-controlled Gazprom Media owns a majority stake in Ekho Moskvy, it could change the station's editorial policy by replacing the editor at any time. For now, the authorities do not need such a shake-up because Ekho Moskvy helps them compete with the opposition. Venediktov does not have job security, but as long as he is editor-in-chief, his editorial policy guarantees that this status quo will largely remain intact.

Robert Orttung is assistant director of The George Washington University's Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies (IERES). Sufian Zhemukov is senior research associate at IERES.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.