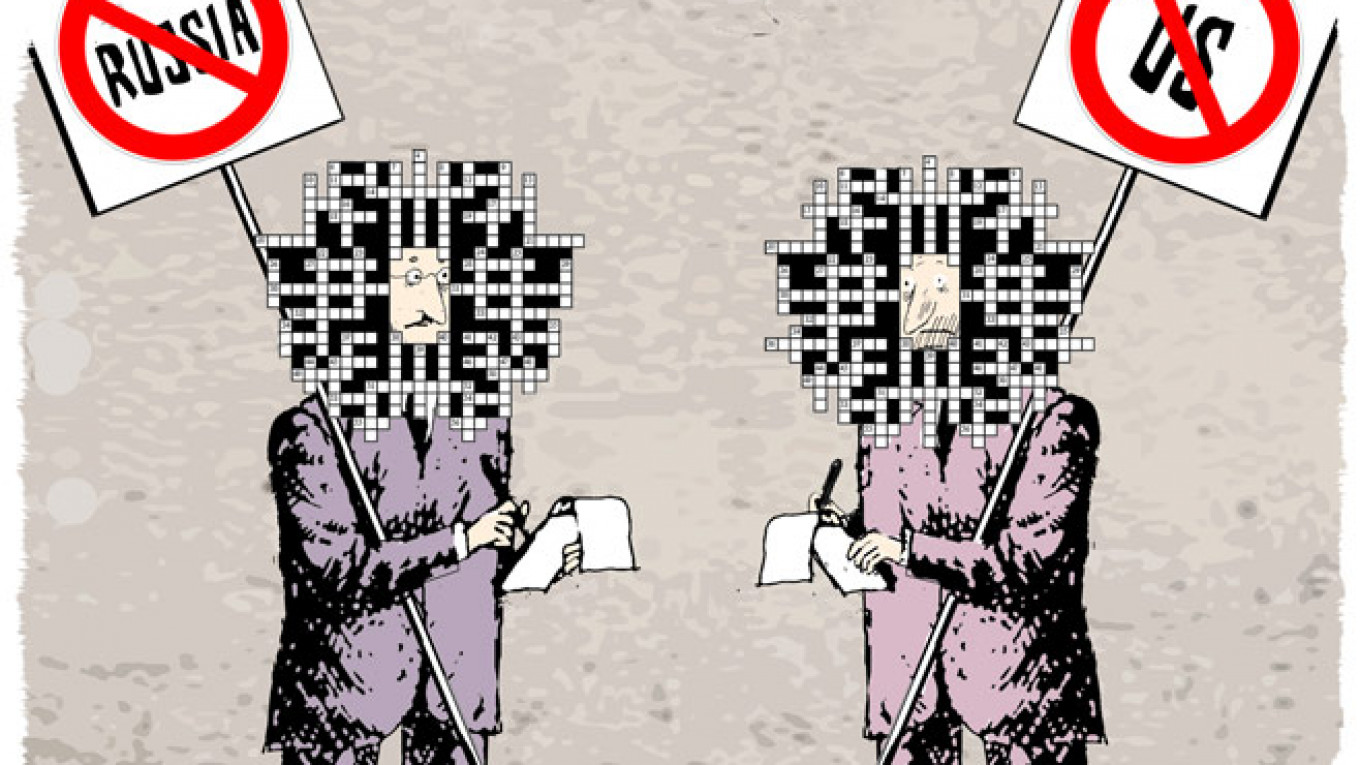

Western newspaper headlines tirelessly warn their readers that anti-Americanism in Russia is exploding. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the fluctuating attitudes of Russians toward the United States have been monitored on a regular basis by the Levada Center, Russia's leading independent pollster.

The latest Levada poll results confirm that just over 80 percent of Russians view the U.S. in a negative light. It is worth noting that this is the highest negative rating for the U.S. since the center first began tracking the views of Russians on the other superpower in 1988.

While Russia's growing anti-American sentiment is no longer a secret, is the reverse also true for Americans? Although cultural stereotypes about Russia in the West are gradually fading into the Cold War past of the Soviet era, Russophobia in the U.S. is also on the rise.

A Gallup poll conducted in February demonstrates that Americans' views of Russia are at their least favorable (70 percent) in Gallup's 26-year trend. These were sociological polls conducted among a broad cross-section of American society.

There is a personal motivation behind my interest in the current state of U.S.-Russian relations. My original plan to pursue the far less political field of child psychology was sidetracked when, by the end of my first year at Columbia University, I became increasingly interested in the question of post-Soviet national identity and the peculiar political relations and cultural ties between the two former superpowers.

Born in Soviet Georgia and bred in post-Soviet Russia, I spent the majority of my post-formative years in the West, which may partially explain why I am drawn to the complexities of national identity and the psychological impact of the collapse of the Soviet Union.

On a frosty winter morning in the early 1990s, as my mother and I — recent immigrants from war-torn Georgia — walked into the supermarket on Novy Arbat, I was surprised to see a vast store jammed with shoppers, the majority of whom, due to astronomical price tags, were strolling along with empty carts and curious eyes.

Although the shelves were no longer empty, the term "consumerism" continued to sound tantalizingly exotic to our post-Communist ears. A distant American illusion implied by formerly banned Western commodities, aspirations and ideals served my generation as a colorful escape from the mundane reality, providing us with a faint glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel.

Alas, those days appear to have long vanished, and along with Russia's sanctions on many Western food products came the inevitable intolerance for most things American.

These days, anti-Americanism is often synonymous with die-hard patriotism and Russian nationalism.

I am now contemplating an academic shift in the direction of Russian studies as my primary focus. With the pending shift in mind, I pondered how my faculty would view my unexpected decision to switch gears.

Even though both anti-Americanism and Russophobia seem to be on the rise among our two nations, the ever-growing interest in and to a certain degree fascination with what's next for the U.S.-Russian relationship is difficult to ignore.

Some 3,000 feet over the Atlantic Ocean, I typed these words on the ultimate capitalist-consumerist machine of our time — a Mac laptop — and considered the irony of the 24-hour route to my final destination. Boarding the plane in New York's JFK Airport, flying into Moscow for a morning meeting and immediately afterward catching my next flight to Tbilisi all in one day encompassed the three contrasting ideologies of my childhood in the dying days of the Soviet Union.

This particular route offers a telling snapshot of my cross-linguistic, socio-psychological research trip to study the intricacies of the Georgian national identity in correlation with the cultural and political post-Soviet heritage of the Russian language. Not surprisingly, this is a subject that some of my compatriots in Georgia view as a potentially hazardous can of worms that may be better left unopened.

Announcing the decision to study my adopted country and analyze its current — and undoubtedly bumpy — relations with my homeland was met with a mixture of excitement and intrigue among university peers and faculty members, especially during the seven-year anniversary of the Russian-Georgian War of 2008.

It is, without a doubt, a symbolic time for me to embark on a research trip that aims to analyze the relationship between Georgian national identity in the post-Soviet era and the role of Russian as the former mandatory second language.

Over the past decade, the U.S. government and private foundations have reduced funding for Russian studies, but the interest in the area remains alive and kicking. Unlike my Georgian peers who skeptically raised their eyebrows, my mentors in the academic field welcomed the shift, stating that the theme is both "pertinent" and, sadly, unexplored.

While Russophobia in Georgia has been on a rapid rise in the aftermath of the five-day war, speculation about the growing anti-Russian sentiment inside U.S. academic circles may be inaccurate. Of course, one could view the increase of fascination, interest and intrigue fueled by the current political climate in the Russian Federation and its tumultuous affairs with the West as a sign of partially anti-Russian sentiment.

However, in the words of the Chinese military general, Sun Tzu, it is best to "Know your enemy and know yourself, and you can fight a hundred battles without disaster."

Tinatin Japaridze is a Georgian-born, Russian-bred Columbia University student currently studying cultural psychology and Russian studies.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.