Classical Russian culture centers on literature: Many decades after they first appeared, the works of Alexander Pushkin, Nikolai Gogol, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy, Vladimir Nabokov and Mikhail Bulgakov are frequently quoted, remain the foundation of contemporary art and even influence political decisions at times.

Paradoxically, the quintessential catchwords of Russian literature have become "Who is to blame?" and "What is to be done?"

The paradox lies in the fact that those questions are actually the titles of two 19th-century books that were examples of outstanding Russian journalism and not classic literature.

The question "Who is to blame?" is the title of a book from 1846 by Alexander Herzen. One year after its publication, Herzen suffered a fate very relevant to today's situation. Unhappy with the sharp-tongued emigrant, Tsar Nicholas I attempted to seize Herzen's property in Russia, but the Rothschild bank said it would extend loans to the Russian government only if it did not proceed with that arrest. After that, Herzen's full rights were reinstated but he did not return to Russia.

The question "What is to be done?" is the title of a utopian socialist novel that Nikolai Chernyshevsky wrote in 1863 while awaiting sentencing for writing political proclamations, works that earned the author 20 years of penal servitude in exile.

Both works were required reading in every Soviet-era literature class and were presented as milestones in the development of class thinking. Those works managed to bore nearly every school student and many of their teachers as well.

In fact, Herzen and Chernyshevsky were more political than literary figures — although the two fields are often inseparable — and were, with all due respect to their unquestioned merits as authors and publishers, somewhat divergent from mainstream Russian literature.

The two authors knew each other, and the catchy titles they gave their works — a seeming mutual polemic — have clearly outlived the content of the books themselves. The questions "Who is to blame?" and "What is to be done?" are probably the most frequently quoted passages from 19th-century Russian literature.

In fact, those two questions arise today in any situation where Russians must make a decision. This is because, whether or not the decision makers ever read Chernyshevsky and Herzen, they must first assess the current situation and the factors that led to it and then formulate possible strategies for coping with it.

However, modern Russian society is prepared to answer only one of those two questions: "Who is to blame?" People are divided on the answer, some arguing that President Vladimir Putin has caused all of the country's problems, but far more hold the opinion that the crafty and nefarious West is to blame for everything from the unequal balance of power in the world to a close friend's recent divorce.

In between are countless conspiracy theories and the like, but overall, Russians are more than ready to assign blame to somebody else for their problems.

Thus, Herzen's burning question is not forgotten.

The same cannot be said of Chernyshevsky's question.

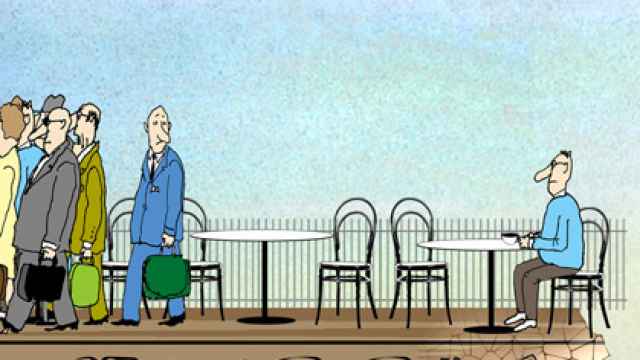

As the average Russian sits down with his morning coffee, turns on his computer and scans the latest posts on social networks, he finds every manner of accusation concerning who is to blame for the current difficulties: "Obama wants to take Ukraine away from Russia," "Putin has pushed the country into isolation," "Stalin destroyed the gene pool," "Gorbachev and Yeltsin broke and stole everything," "By turning toward the West, Peter the Great destroyed traditional Russian spirituality," and so on.

And because assigning blame is essentially a negative process, every response framed in that spirit tends to cast Russia's future in a negative light. As a rule, most commentators argue that Russia either has no future at all, or that its prospects are bleak.

Even official Kremlin spin doctors probably feel awkward painting a rosy picture of Russia's future when leaders order the destruction of banned food products in a country that still has fresh memories of the hunger and consumer goods shortages during the final years of Soviet rule; when plans to ban imported pharmaceuticals could put the lives of millions of Russians at risk — and all for the questionable theory that it will help domestic producers — it is difficult for even those who earn good money putting a positive spin on events to envision a bright future for the country.

And whereas Russians have no shortage of terrible scenarios, their lack of optimism prevents them from developing almost any realistic plans for the future. It is not in vogue to ask, "What is to be done?"

But that is strange. It is like a group of hikers who find themselves on a failing suspension bridge and, rather than finding a way out of their predicament, spend their time bickering over who is to blame — the guide blames the people who built the bridge and the hikers blame the guide for having led them into danger.

Nobody offers any ideas on how to avoid disaster or how to recover afterward — or even after a few political corrections to the current course. How can Russia regain the world's confidence? How can this country once again attract investors? How can it build the necessary infrastructure?

How can Russia avoid falling into the same trap of the last 20 years when corrupt and narrow interests outweighed the common good? How can Russia avoid becoming so backward and marginalized that even its own citizens lose interest in it?

Even the most politically active and clear-thinking youth have no better answer to the question of "What is to be done?" than: "We must replace Putin." The question of how to accomplish that task is almost never discussed. Neither does anyone explain why a leader with a different surname would behave any differently than Putin under the same political circumstances.

But if an answer does come, it is often the disappointingly naive: "Because anyone else is better than Putin." And no attention is given to the question of how to introduce institutional guarantees to prevent even the most well-intentioned reformer from becoming an autocrat, despot and patron of high-level corruption.

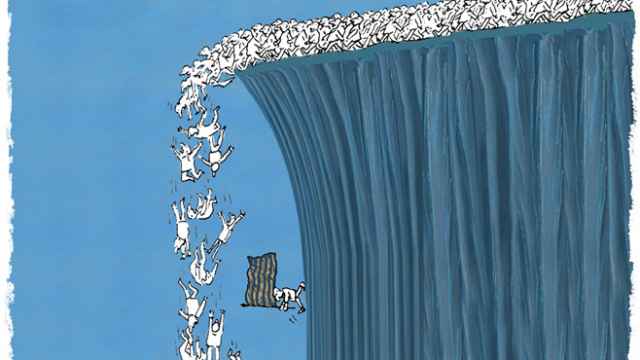

I believe that Russians do not have an "escape plan" from their troubles because they have grown accustomed to misfortune. After suffering two national collapses in a single century — in 1917 and 1991 — two world wars and decades of a government that essentially waged war against its own people, Russians now reflexively begin preparing for the end of the world at the least sign of turbulence. Of course, the end of the world is terrible, but at least it does not require people to think about what comes next.

Russia really does have little hope of a bright future, but it is not necessarily headed for doomsday either. All the same, it is time to set aside our infatuation with past suffering and mutual recriminations and focus our efforts on finding an answer to the question: "What is to be done?"

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 15 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.