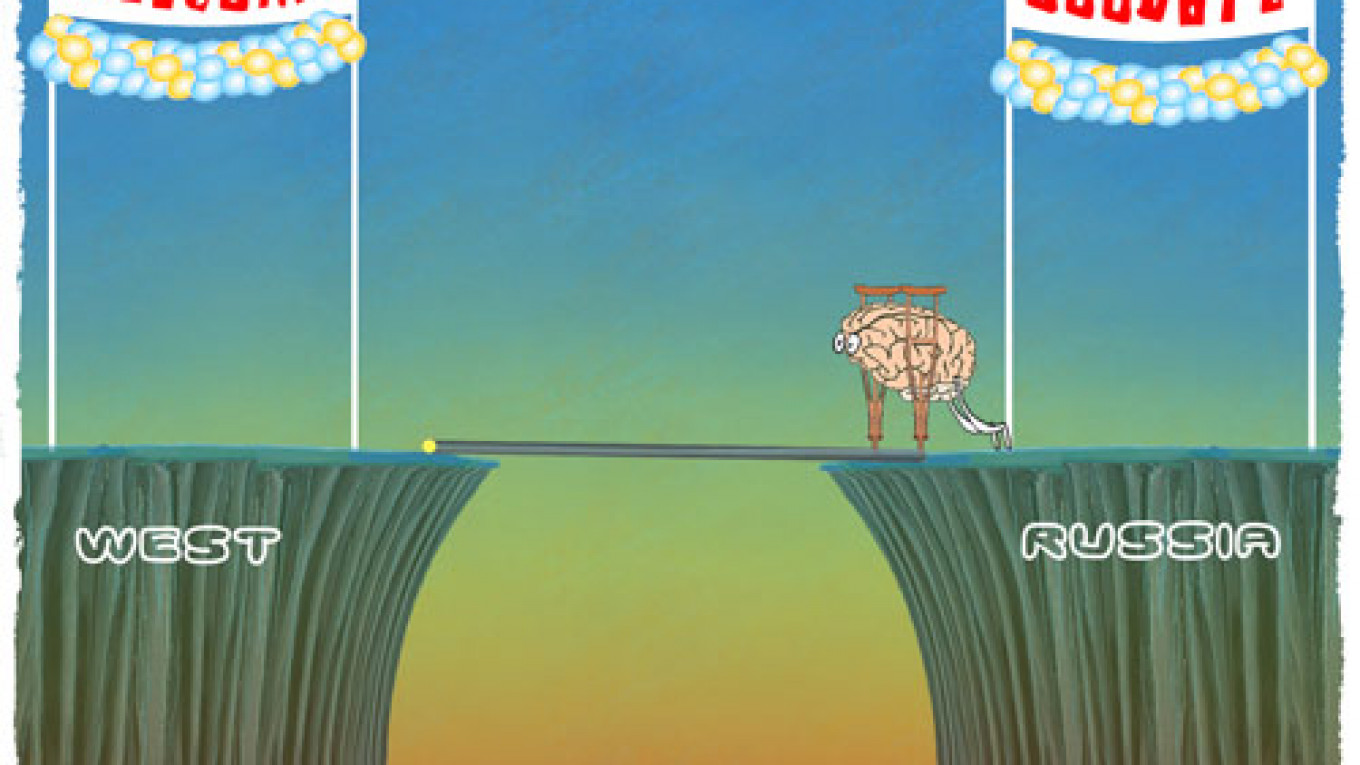

Russia is locked in a confrontation with the West, and all those who work or study there are increasingly viewed as deserters or betrayers. On the other hand, the ruling regime has not yet closed the borders, perhaps feeling that it is better to let its critics — those at odds with Russia's "moral majority" — leave the country than to remain behind and create a "fifth column" of opposition.

On the other hand, if the country's education system continues to degenerate at the current rate, the problem might go away by itself when there are no more brains left to drain.

Figures on the Internet vary concerning the scale of the exodus. Some put the number at 200,000 over the past two years. Official statistics claim that only 20,000 Russians have moved abroad during that period. And the departure of each prominent public figure is accompanied by malevolent — and perhaps envious — cries of, "Yet another one has fallen out of the nest and chosen freedom," or else, "That's what this bloody regime deserves."

Opinion surveys of the youth — most of whom supposedly want to jump ship — are intended to demonstrate that Russia has no future. However, it is a long way between saying you want to leave and actually doing it. For many youth, the desire to leave Russia is more of a protest pose than a concrete plan.

In fact, approximately the same percentage of youth in more economically developed countries expresses a desire to leave. The world is changing. Leaving your homeland nowadays is nothing like it was in the late 19th century when the Irish emigrated to escape famine or when Russian Jews, fleeing pogroms at home, dropped to their knees and kissed the ground as they disembarked from their ships on Ellis Island and first glimpsed the Statue of Liberty. Those emigrants left their homelands forever.

Now a person can go live in a second country, study in a third, holds jobs in several more and then retire to a warm seaside locale in yet another. However, many Russians continue to judge such globe-hopping with a prejudice hearkening back to the Soviet era, when anyone moving abroad was stripped of their native citizenship.

The problem of brain drain is connected with the country's level of technological development, its global competitiveness and its place in the world economy. Russia is currently going through a difficult phase. On one hand, leaders are constantly telling the people that Russia will not fence itself off from the rest of the world, and ratings indicate that they are concerned about improving the country's competitiveness.

On the other hand, when official propaganda describes the outside world as hostile, it is difficult for Kremlin spin doctors and legislators to avoid the temptation of adding yet another brick to the wall separating Russia from the host of its "enemies."

It has become the political fashion whereby officials question the transparency of international scientific and educational exchange programs or express intolerance toward the invading "alien" values. Propaganda has fanned support for autocracy, a "besieged fortress" mentality and the belief that the West does not love or understand Russia and only wants to "enslave" it.

This has prompted a rise in archaic patriotic traditionalism under the slogan: "Russia follows its own path." Backwardness has become the guiding principle of the government at almost all levels, as if leaders want to exact revenge on Peter the Great for attempting to open a window to the outside world and modernize the country.

Decision makers are losing their awareness and their desire to know how the modern world functions and which trends will shape the future. That backwardness contributes to the brain drain among people who see few opportunities for self-realization in modern Russia.

Recognizing that Russia can still learn a thing or two from the rest of the world, the government allocated 4 billion rubles ($63 million) to fund education costs for up to 1,500 students who would study in any of the 225 fields in prestigious foreign universities on the condition that they return home after graduation to work in their specialties.

I was recently surprised to learn that the program had very few takers and that the government has since cut the number of slots down to 750 — while doubling the stipend for each. What's more, many of the Russian firms originally slated to participate in the program now show no desire to receive graduates who return from overseas full of "foreign ideas."

Does that mean Russia's economic and management systems have no need for Western-educated minds?

Roughly 50,000 Russians studied abroad last year — three times more than in the 1990s. Some observers claim that greater numbers of those students are now returning to live and work in Russia, although for many, a foreign university degree remains the best chance to gain a foothold overseas and start a new life there. Will an increasing number really come back to Russia? I doubt it.

This is first due to the decline in Russia's system of education, especially higher education. It is increasingly becoming a profanation of education, as instructors earn humiliatingly low salaries and lack the opportunity or even the motivation to maintain and improve their professional qualifications.

The quality of the graduates from such institutions necessarily suffers also. Who needs such non-competitive "minds"? The rate at which the educational and technological chasm between Russia and the world's leading countries is growing will only increase.

Already now, Russia's scientific institutions and universities lack access to everything from subscriptions to the latest technical journals to modern lab equipment. That will one day take its toll.

The second reason is both ideological and psychological. Life in Russia is simpler and more familiar. Western society requires residents to jump through numerous hoops in order to live a highly regulated lifestyle — in contrast to what Russians had imagined about the West back in the late 1980s. The difficult demographic situation in Russia also means that jobs are available for practically everyone, including the dullest and laziest.

The low overall level of competency in all fields makes it possible for employees to earn more money with less effort than comparable workers in a more competitive country could ever hope to bring home. And the "informal" but illegal arrangements that characterize so much of Russian life make it possible for people who excel at such things to earn a tolerable existence without much hassle.

In addition, the government has enough cash in its coffers to afford such a lazy lifestyle to state employees and their dependents for at least another 10 years. Today's Russian youth would prefer a cushy government job with little responsibility and great "side benefits" to a diploma from Harvard. But their real dream is to land a career with a state corporation where illicit wealth abounds for anyone with gumption and little regard for principle.

Thus, the number of Russians adequately skilled in their professions to work in the outside world will rapidly decline in the near future. And when the question arises, "Is it time yet to get out of here?" the answer will increasingly be: "Nobody needs you over there, anyway."

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.