An old college friend whom I have known for more than 20 years is planning to leave Russia for good in early September.

Like clouds gathering before a storm, both close and distant acquaintances are increasingly talking about leaving Russia. Announcements to that effect are already trickling in, and they threaten to become a heavy downpour soon.

However, it is unlikely to become an ongoing flood of emigrants: In the quarter-century since the fall of the Iron Curtain, only a little more than 10 percent of all Russians have traveled abroad — even including the massive numbers that have visited Egypt and Turkey. In fact, only a minority of them plan to leave Russia forever.

My parents, who have been abroad, are constantly advising me — someone who travels abroad regularly — to move away, that Russia has no future for us or for our children. At the same time, they putter around their dacha every summer weekend and clearly show no desire to ever sell it and leave.

And yet that steady trickle of departing friends comes like the steady beating of raindrops on the rooftop in Moscow's drizzly July. The fact that relatively young and educated people are leaving the country is already enough to convince even the uninformed that something is wrong in Russia.

I still clearly remember the day when I first learned that people sometimes leave the country. It was Sept. 1, 1991: Soon after the abortive coup attempt in Moscow took place, I began my penultimate year at high school only to learn that our Russian teacher had emigrated. Even as teenagers we understood her rationale for leaving: The dramatic political events unfolding meant that our old lives had ended and that insecurity and uncertainty were on the rise.

By contrast, those who are now considering leaving lack a clear-cut picture of exactly what is happening in the country.

People consider leaving due to three main concerns: that the economy will collapse, that deepening authoritarianism will either cause the system to fail or take everyone else down with it, and that the rising generation will enjoy few prospects.

There are so many unpredictable factors and worsening indicators that it seems unlikely parents will manage to properly educate their children or help them to lead productive and secure lives in Russia.

Nobody knows just how bad things will get with the economy. However, it is clear to most that the ruble is likely to suffer another sharp devaluation like the one that occurred in late 2014 and that more troubles will follow. And yet, members of that segment of the population most likely to emigrate still earn higher salaries in Russian than they are likely to earn if they were to move abroad.

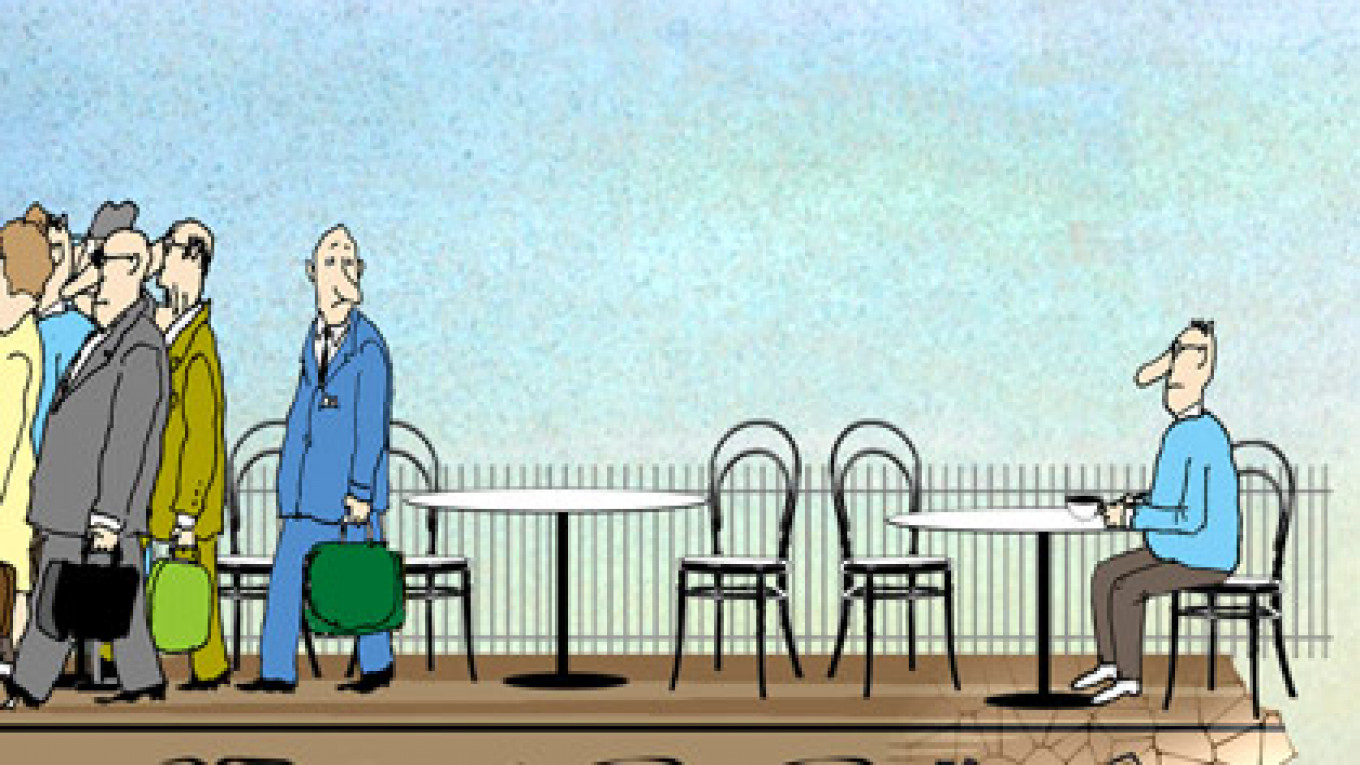

In fact, the cheaper ruble is dampening emigration ambitions for many Russians. A cup of coffee at the airport costs the same $5 as before, but it now requires twice as many rubles to buy it. On the other hand, apartment rental fees in Moscow have not doubled, leading many property owners — accustomed to using that income to live overseas while maintaining jobs in Russia — to return home, sometimes with the added problem of having lost their cushy jobs.

It is one thing to escape Moscow's depressing winters with the help of vacations to eternally sunny Southeast Asia, but quite another to relocate overseas permanently. However, some might risk a possible drop in income and make the move anyway, either because they dislike the political uncertainty at home or, to the contrary, anticipate an inevitable increase in authoritarianism.

It is customary to argue that the authoritarianism in today's Russia is just window dressing compared to Soviet-era, and especially Stalinist practices. In fact, Russians respond very passively to such developments as the clash that occurred on May 6, 2012 between police and demonstrators who were protesting the falsification of election results or the current crackdown on nongovernmental organizations that receive foreign funding.

People tend to view such things as they would a foreign war. They might sympathize with the innocent victims and yet believe that, since they themselves do nothing but drink their coffee and read their newspaper, the problem won't affect them. According to that logic, only crazy alarmists could compare the trickle of today's political excesses with the flood of abuses that characterized the Great Terror of the 1930s.

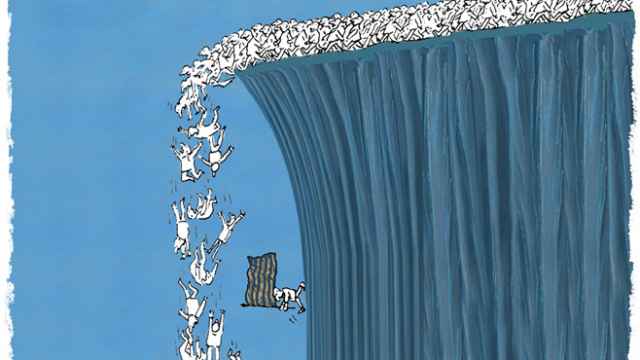

However, the terror of the 1930s also began with a trickle. Russians have only superficially examined that national tragedy and have never really given it a proper ethical or legal evaluation. Where is the guarantee that the authorities' decision to charge a 75-year-old physicist with high treason for having contact with foreigners will not open the floodgates of repression, eventually turning the current trickle into a flood?

Another common misconception is that, although the ruling regime is admittedly imperfect — and the Crimean adventure might really have some connection with the weak ruble and problems in the real estate and labor markets — trying to replace it might only lead to something worse, perhaps even a more rigidly autocratic regime.

Strangely, many people choose to remain in Russia despite their belief that the country has no future as long as President Vladimir Putin remains in power — even though a blind person could see that this regime greatly differs now from what it was two, three and especially five years ago. Those people contend that although the future is bleak, as long as things are more or less moving along, there is no reason to worry.

These are all reasonable and logical arguments. However, few people think about the fact that the current situation is that same negative future that my Russian teacher and others foresaw 25 years ago, and that even then threatened to reach such lows as to make it necessary for us, her students, to leave the country as well.

Many people intuitively saw it coming even then, but felt it was easier to just go along with the flow than to live and act and in such a way as to bring about a different future, one that would make it worthwhile to stay in Russia and not emigrate.

We Russians have brought about this future ourselves, and we continue on even now in the same direction. Each person has their own pain threshold that would justify a decision to leave, but when the very social group that might have transformed Russia for the better decides to opt out, it begins to resemble players who turn over the game board when they realize they have little hope of winning.

I have no one to blame but myself. I am one of those who simply stood by as events reached this stage, and I am one of those who constantly thinks about leaving. My one concern is that it might not prove so simple to build a better future elsewhere if we lacked the skill and tenacity to do it here.

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 15 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.