Maria Gaidar's decision to move to Ukraine and become a deputy to Mikheil Saakashvili, the former president of Georgia and the current head of Ukraine's Odessa region, sparked a storm of controversy in Russia. She was condemned not only by die-hard ultrapatriots, but also by many who normally criticize the Kremlin — including for its position on Ukraine.

The slogan "My country — right or wrong!" no longer motivates Gaidar, a leader of the democratic opposition, daughter of former Prime Minister Yegor Gaidar — who headed the government during the difficult months of the Soviet collapse — and great-granddaughter of well-known Soviet-era children's author, Civil War hero and tireless propagandist of socialism Arkady Gaidar.

"My country — right or wrong!" is apparently the logic by which some Russians view Gaidar as a traitor to her homeland.

In fact, that slogan symbolizes the debate over questions far more important than Maria Gaidar's decision to work for the Odessa administration.

There is no categorical answer in this debate — however much some would like to invoke principle in pronouncing one.

No matter how quickly the world around us changes, some things remain the same. Perhaps it is an anachronism, but there are still people in the world for whom "loyalty to the national flag" is not just an empty phrase. Such people live in Russia, the United States, Great Britain, China and even in unrecognized states. There are people who place great importance on the place where their parents lived, and where their children will live.

Most people have a sense of homeland. The global economy can yank members of the upper middle class all over the map — from work in Hong Kong to a job six months later in London and then to Sao Paulo, but most people want to be able to return home. They love their homeland, although it might fall far short of their dreams at times. And we love our country, whatever problems it might encounter.

Russia is one country that is lacking in love.

That causes both the people, and strangely, even the country itself to develop a psychological complex.

I cannot gauge the depth of feeling of the "patriotic majority" that supports the current regime, but my life experience and knowledge of Russian history suggests that it is somewhat overstated. However, I can unequivocally state that very few Russians who take an active interest in the country's political life exhibit any great allegiance to the national flag.

Of course, there is a large group of scoundrels who, sensing the mood of the senior authorities, has made money and careers out of masquerading as patriots. And there is a second group that earns money for exposing the insincerity of the first, and a third group that pays the second.

Paradoxically, Russia's economy leaves many people little choice but to earn their living either directly or indirectly from the very government system they so often criticize on social networks. The authorities naturally distrust them as a result. After all, would you trust someone who accepts your paycheck even while slamming you on Facebook?

This is a repeat of events at the turn of the 20th century. In the decades before the revolution, criticism of the Russian Empire became endemic among the very classes that could have helped improve the Empire. That became a trap for rulers and critics alike. The authorities severed ties with highly competent individuals who voiced hostility to their rule and allied themselves with incompetent patriots. That led to the inevitable collapse of their regime. At the same time, all their intelligence only won the critics — who were dependent on the very authorities they railed against — time in concentration camps in the east, forced exile in the west or obscurity in a homeland that no longer belonged to them.

Do the people who today so fiercely criticize the government of President Vladimir Putin seriously imagine that after the current phase of Russian history concludes they will manage to change the political foundations of the ruling regime — especially considering that many of them are part of that regime and even relatively prosperous as a result?

The probability of such a scenario is low. To succeed, they would have to evince greater allegiance to the national flag and at least enough love for Russia to want to build a home for their children here rather than in some other country. Instead, they worry more about their iPads and plane tickets to foreign destinations while issuing a constant buzz of critical commentary that eventually degenerates into meaningless white noise.

But I cannot bring myself to angrily proclaim that the sooner such people leave Russia the better. This is because I know that the slogan "My country — right or wrong!" is often used to justify violence, legal abuses and attacks on human dignity, and that the situation here might soon deteriorate to such a degree that questions of homes for our children or loyalty to the flag would become moot.

There is no definitive point at which patriotism, taken too far, becomes instead a refuge for scoundrels. Each of us weighs numerous circumstances every minute of the day on our own "internal scales."

Today, the authorities label friends who work for human rights as "foreign agents," but tomorrow a fashionable photo exhibition opens in downtown Moscow that seems to belie the impression that the country is sinking into archaic totalitarianism.

The Kremlin opposes the creation of a tribunal concerning the downing of a passenger plane over war-torn eastern Ukraine one year ago, while the average citizen is too busy trying to make ends meet or care for ailing relatives to properly assess what responsibility this country holds for those deaths.

This situation has arisen many times in the past, and even in recent German history as well. The limits of what is considered tolerable or conscionable have always been subjective. One such German "gatekeeper of rectitude" was the author and social critic Thomas Mann, another was novelist Gunter Grass, a third died in the Nazi concentration camp in Dachau. A fourth lived through the entire period from 1933 to 1945, listening to the radio after dinner every day and never experiencing any personal tragedy, even when one neighbor lost a son at the eastern front and another lost a wife during the Allied bombing.

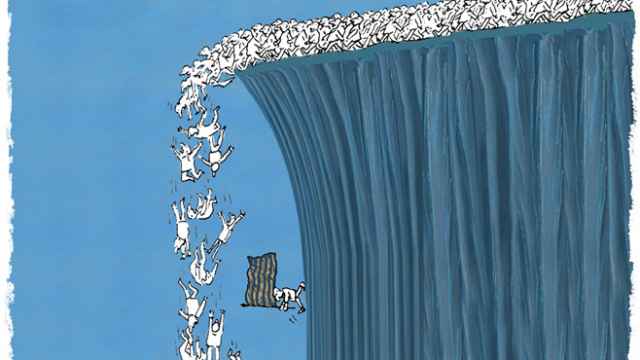

Maria Gaidar has determined her own internal limits, and her actions in no way represent an act of treason. Many thousands of Russians outside of the public eye have also found it difficult to breathe in the atmosphere of modern Russia and have already left for Kiev, Berlin, Boston, Haifa and Shanghai, among others. And those numbers will probably grow. It is even possible that some of those who today, while taking a critical stance toward Putin, accuse Gaidar of acting improperly when Russia is effectively at war with Ukraine, will join her in Kiev at some future date when they finally get fed up with life here.

Perhaps, if all of those people had not left their homeland, more like-minded citizens would have remained in Russia to turn the situation around.

But maybe life and freedom are more important than allegiance to a flag — especially if that flag now stands for the denial of those liberties.

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 15 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.