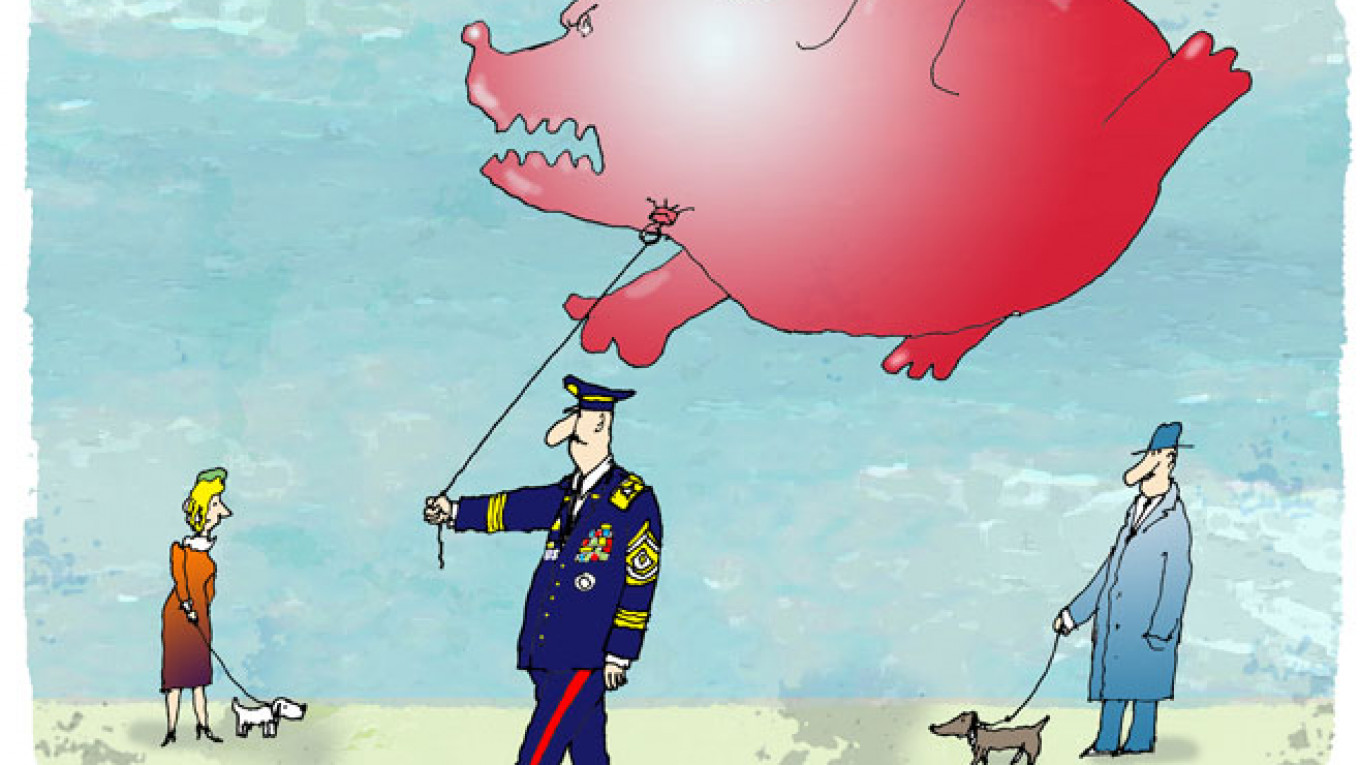

Suddenly, it seems, America has decided that Russia is a threat, even an existential one. Really?

Air Force Secretary Deborah James said: "I do consider Russia to be the biggest threat." Nonetheless, she comes across as positively dovish alongside with House Armed Services Committee Chairman Mac Thornberry, who feels Russia is the "one country that clearly poses an existential threat" to the United States.

Politicians are expected to say striking things, though. It is even more noteworthy when it becomes part of the military narrative, too. Speaking at his confirmation hearing to be the next chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Marine Corps General Joseph Dunford unequivocally affirmed that "Russia presents the greatest threat to our national security."

Still, a sufficiently senior general, especially when he's looking for confirmation of his appointment, is a politician as much as a soldier, so should this be written off as mere rhetoric?

To an extent, probably. Given that at the same time it is planning to cut 40,000 troops, Washington doesn't appear to see a threat looming. Secretary of State Kerry, the White House's propitiator-in-chief, hurriedly walked Dunford's words back.

However, language matters. Words form narratives, narratives shape political imaginations, and policies are the product of those imaginations. Just as Moscow risks getting caught in a net of its own rhetorical hyperbole (the hunt for "foreign agents," Putin's warning to the West not to "mess with us," and the like), so too can Washington.

How, after all, does Russia pose a threat — an existential one, at that — to the United States? In theory, its nuclear arsenal means it could devastate the country, but the essence of threat assessment is capability plus intent. Otherwise Washington could just as easily consider nuclear powers Britain or France "existential threats."

Does Moscow have the desire to go to war with the United States? There seems no evidence that this is in the slightest degree true. Frankly, the best of Russia's forces are already pretty much operating at capacity in Ukraine: there may be "only" 10,000-12,000 troops at any one time, but as units rotate through, they then need to rest, rearm, regroup and make up their casualties. The rest of the military, heavy on conscripts, short on experience and discipline, is much less than meets the eye. In a war with a richer, more populous and more militarily advanced NATO — even excluding the United States and Canada, NATO has almost three times as many active duty personnel — Russia would not prosper.

While some suggest that Moscow's great power pretensions and Vladimir Putin's need to maintain his image as a strong nationalist leader might make the world stumble into crisis, as it did in World War I, even this seems far-fetched. There are robust diplomatic structures in place; the Kremlin's control over its conventional and nuclear forces is beyond doubt; and neither Putin nor those in his immediate circle are imbeciles or the kind of zealots who would put their comfortable lives at risk.

After all, this is a regime interested in retaining power and asserting its status and sovereignty rather than imposing an ideology abroad or even some dream of expansion. Putin is hardly looking to reconstitute the Soviet Union or the Russian Empire.

Nonetheless, Russia really is a challenge to the West, just a rather different challenge from that which the Dunfords and Thornberrys may suggest.

Russia is clearly a danger to its weaker neighbors, as both Georgia and Ukraine discovered. But by its capability and willingness to intervene in sovereign countries, outside the bounds of international law, it also challenges a global order the West created and which so benefits the West.

Secondly, Russia is a threat not in terms of tanks on the border and missiles in the sky, but its capacity to obstruct and disrupt. From the Iranian nuclear talks and the struggle against the Islamic State, to resupplying the International Space Station and fighting the global drug trade, Moscow can be a useful partner — but also a problematic spoiler should it so choose.

Thirdly, the more the West puts pressure on Russia through sanctions and isolation, the more it bolsters the regime in the short term, but builds up pressures in the long term. This could see the Kremlin adopting a more conciliatory policy in the future, but it could also play to ultra-nationalists of the sort who'd make Putin look like Pussy Riot. This may be a geopolitical gamble worth taking, but it is a gamble nonetheless.

Finally, the confrontation poses an internal, political challenge for a West already divided. Not every government is as committed to the struggle to contain Putin's Russia, let alone every population. To Italy, the real European security challenge comes from the south. In Spain, 50 percent youth unemployment is a more serious issue. In Germany, the people fail to be as enthused as Angela Merkel about facing down Putin. And so it goes.

The current rift between Moscow and the West is wide, deep and treacherous enough. While inflammatory language — from either side — may win a round of applause from a core political base, it only opens that rift wider. And from the West's point of view, the more it focuses on an imaginary "existential threat," the more it loses focus on the other, more real challenges ahead.

Mark Galeotti is professor of global affairs at New York University.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.