Armenia is Russia's main ally in the Caucasus and, at the same time, one of the poorest countries of the world. The mass protests that broke out in Yerevan a few days ago could become a serious test for the regime of Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan as well as a test of the strength of Russia's position among the former Soviet republics.

Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Belarus, member states of the Customs Union and the Eurasian Economic Community, all have authoritarian political systems, unstable economies, strong monopolies and widespread corruption. They also lack the means for achieving a peaceful transfer of power.

As a result, each of those ruling regimes is vulnerable and Moscow knows that the collapse of just one of them could destabilize the entire region and strip Russia of its influence over that particular country.

Armenia has not managed to avoid coups and political terrorism in its post-Soviet history. A quiet revolution by the country's siloviki in 1998 replaced the first Armenian president, Levon Ter-Petrosyan, with the Defense Minister and former leader of Nagorno-Karabakh Robert Kocharyan.

Gunmen shot Armenian parliament members in October 1999, killing, among others, Speaker and Prime Minister Vazgen Sargsyan. The current president, Serzh Sargsyan, was then head of Security and Internal Affairs and succeeded Kocharyan as head of state in 2008. Essentially the same group of individuals has held power in Armenia ever since 1998.

Armenia is a landlocked country sandwiched between unfriendly Azerbaijan on one side and Turkey on the other. To the south is unpredictable Iran and to the north — Georgia. Locked in a geographic near blockade, Armenia derives 20 percent of its gross domestic product from money sent home by members of the enormous Armenian diaspora living abroad.

Russian companies control the largest sectors of the Armenian economy — with energy foremost among them. Russia also guarantees Armenia's security: its 102nd military base in Gyumri is equipped with the latest weapons, including air defense systems.

In terms of per capita income, Armenia is ranked 152nd in the world, with individual annual incomes averaging just $7,400 — less than all of its neighbors, including even Georgia and Ukraine. In Russia that indicator is more than three times higher, at $24,800 a year, and in Azerbaijan just over two times higher, at $17,000 a year.

A visitor flying in to Yerevan is immediately struck by the huge disparity in wealth there. Endless casinos with gilded columns line the road leading from the airport into town, with luxury cars bearing Armenian and Iranian license plates parked out in front every night. Motorcades carrying local oligarchs and their numerous armed guards speed through the streets of Yerevan, and residents say they must occasionally stop for the motorcades of the country's leaders.

The vast majority of Armenians are very poor and more than 40 percent of all employees work in agriculture. Unemployment remains steady at 15 percent and for decades the Armenian authorities have encouraged able-bodied workers to emigrate in search of greater opportunity.

The population numbers approximately 2.9 million, and approximately 1.5 million Armenians live in Russia. The republic has a major trade deficit, with import volumes double that of exports. That deficit is masked by Armenians abroad sending money home and by the country's growing foreign debt — now almost half of GDP. As much as 36 percent of the population lives below the poverty line.

In Armenia I learned that a small clique of just seven or eight oligarchs owns the main export business — such as famed Armenian brandy — as well as the import business — including fuel, medicines, food, tobacco and sugar — and also strongly influences politics.

Russian companies control a significant portion of the production and distribution of electricity, the delivery and sale of gas, and have a major share of Armenia's nuclear power, communications, transportation and construction industry.

Local monopolists with close ties to the authorities team up with Russian monopolists to fix prices and tariffs at artificially high levels and skim off excess profits while the majority of the population struggles with poverty and unemployment.

On June 17, the Armenian government decided to implement a sharp 16.7 percent increase in electricity tariffs, even though electricity rates in Armenia are already the highest among all the former Soviet republics, and twice higher than in neighboring Georgia. Energy supplier Electric Networks of Armenia is part of Russian energy company Inter RAO.

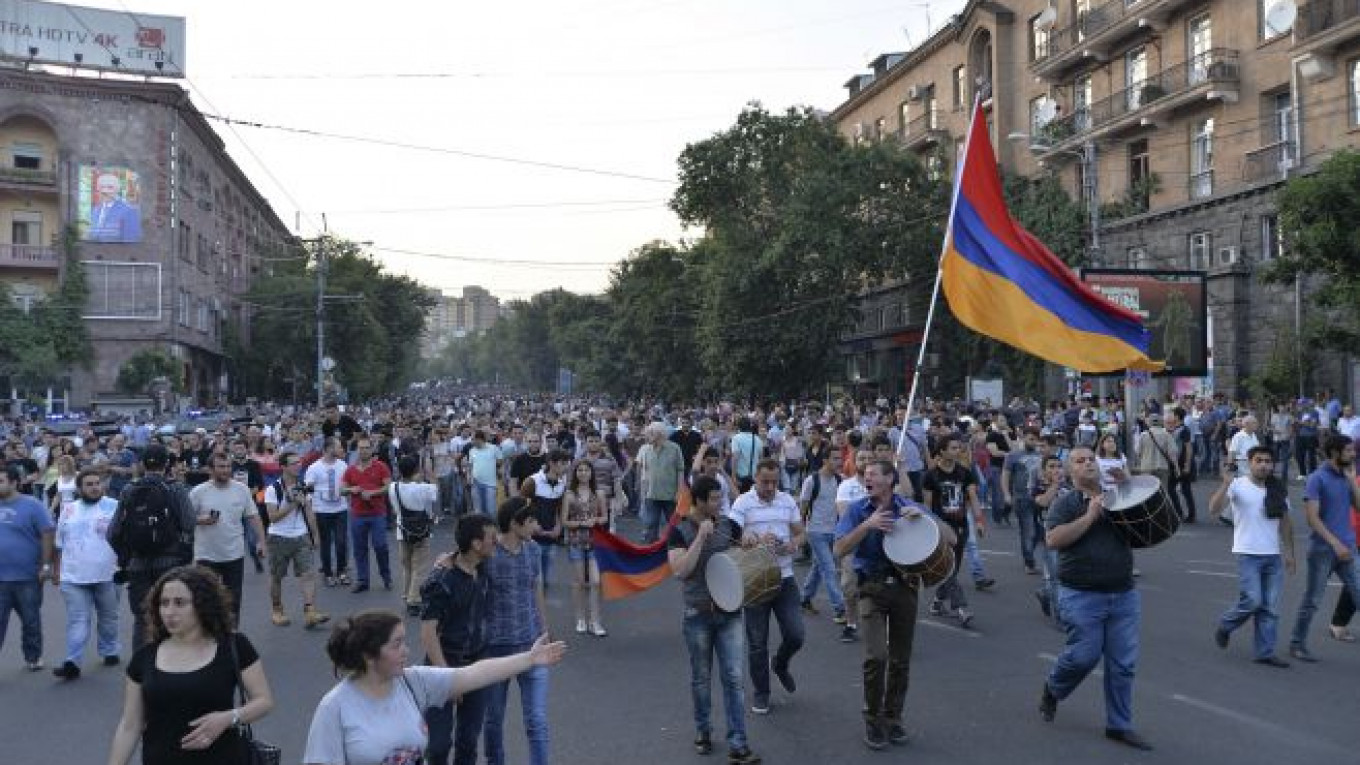

Thousands of residents demanding a repeal of that decision took to the streets in protest and remain there to this day. After riot police beat protestors under the cover of night, demonstrators increasingly began demanding that the president and government resign.

Armenia chose to link its future with Russia rather than the West, primarily for reasons of national security. But the people are tired of poverty, high prices, corruption, social stratification, injustice, oligarchs and the stubbornly entrenched authorities.

The main problem facing the authoritarian regimes of the former Soviet republics is not the machinations of the West that, with the help of U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland, nongovernmental organizations and U.S. State Department "dupes" are designed to overthrow them and turn those countries away from Russia.

Their main problem is their chronic inability to provide economic development and a decent standard of living for their citizens. Under such conditions, even something as seemingly trivial as a price hike in electricity rates could spell disaster for their regimes.

Vladimir Ryzhkov, a State Duma deputy from 1993 to 2007, is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.