Обществозна́ние: social studies

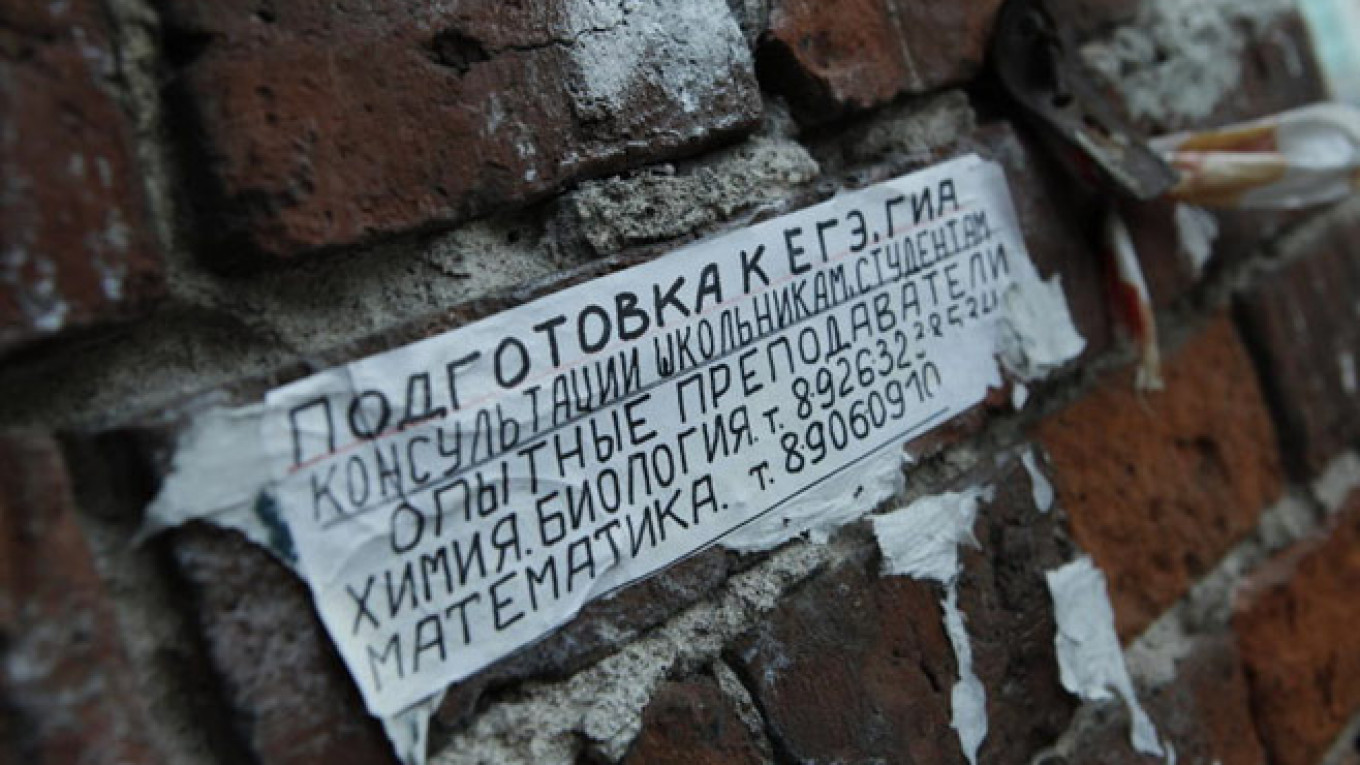

Every spring Russia's youth endures the nationwide torture called ЕГЭ — Единый государственный экзамен (unified state examination) as parents nervously pace and wonder if all that репетиторство (individual tutoring) was worth the thousands of rubles they paid. When it's finally over, the kids find out their scores, parents praise or scold, and everyone breathes a sigh of relief.

That's when the real fun begins.

For several years, some educational departments around the country have been compiling the best bits from the year's exam answers — all those earnestly written, rather confused, but often strangely wise responses. They are a kind of snapshot of what some kids are thinking — and how the education and public information systems are functioning. Besides, they are an excellent language-learning tool.

Take the expression не указ (literally "not an order"). When used with the subject in the dative case, like мне (to me), it means that someone's words "aren't an order to me." This phrase is very popular with teenagers, who like to shout: Ты мне не указ! (You're not the boss of me!)

In the exam on обществознание (social studies), one young person's assessment of the current geopolitical situation sounded more like adolescent acting-out than national posturing: Америка нам не указ, мы ведь даже Путина не всегда слушаемся. (We don't take orders from America — in fact, sometimes we don't even do what Putin says.)

Some of the kids needed a bit more remedial work in history. For example, one student wrote: Сталин обратился к народу и пообещал мочить Гитлера даже на луне. (Stalin addressed the people and promised to wipe out Hitler, even on the moon.) Here, of course, the student remembered Putin's promise to wipe out terrorists in the outhouse (мочить в сортире) and applied it to the wrong leader — and the wrong location.

Another student was shaky about who exactly that Marx guy was: Как правильно зарабатывать деньги описал в книге "Капитал" известный бизнесмен XX века Карл Маркс. (How to earn money the right way was described in the book "Capital," written by the well-known 20th-century businessman Karl Marx.)

The further the kids went back into Russia's historical past, the more muddled they got: Некоторые философы считали, что государство это инструмент обворовывание народа. За это государство рубило им головы и отправляло в Сибирь строить дороги. (Some philosophers believed that the state was an instrument to rob the people blind. For that, the state cut off their heads and sent them to Siberia to build roads.)

Current events are definitely clearer in the minds of Russia's youth. For one thing, they know who the bad guys are: Обама и Порошенко это политики не высшего класса, даже не овощи, а отбросы. (Obama and Poroshenko are not top-class politicians. They're not even vegetables, they're cast-offs.) And they have some plausible theories on why, exactly, крымнаш (Crimea is ours): Крым нужен России на случай похолодания. (Russia needs Crimea in the event of a cold snap.)

But they know the secret of marital bliss — sort of: Если муж не покупает жене колготки, значит, он не исполняет своих супружеских обязанностей. (If a husband doesn't buy his wife stockings, it means he isn't fulfilling his marital duties.) And the secret of success in the workplace: Обученный персонал это тот, кто не сует пальцы куда попало. (Trained personnel are people who don't stick their fingers just anywhere.)

Садись! Пятёрка! (Sit down! You get an "A"!)

Michele A. Berdy, a Moscow-based translator and interpreter, is author of "The Russian Word's Worth" (Glas), a collection of her columns.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.