Deepa Bhasthi for The Calvert Journal.

Grandma would, every now and then, suddenly look at me as if noticing me for the first time, and remark that I had my grandfather's forehead and his quick temper. Grandpa was an Indian freedom fighter turned Communist card holder, an oddity in the 1960s and '70s in small-town south India. He died six months before I was born, leaving behind, among other things, several coats that grandma would later turn into recycled bags and a collection of books that, by virtue of living in the house he built, I almost entirely inherited.

In the little village/town (we could never agree on which it was) where I grew up, it used to rain for over six months a year. In those days, friends didn't "hang out" and phone calls, if the telephone lines were up, were usually for asking after homework. The only newspaper vendor in town sold only pulp fiction. And so it came to pass that the first novel I read as a 10-year-old was Maxim Gorky's "Mother," a beautiful Raduga edition. The hard-bound book had a cream jacket with a picture of an older woman in a black full-length coat, a wrinkled scarf covering her hair, a half-hidden suitcase in her hand. Perhaps I was judging by the cover when I pulled out the book from grandpa's library, but it led to a lifelong love for Russian literature. It was happily aided by the propaganda-ish books that flooded into India in the years before the U.S.S.R. disintegrated: books on literature, science, comics and everything else by publishers like Raduga, Progress, Mir and others.

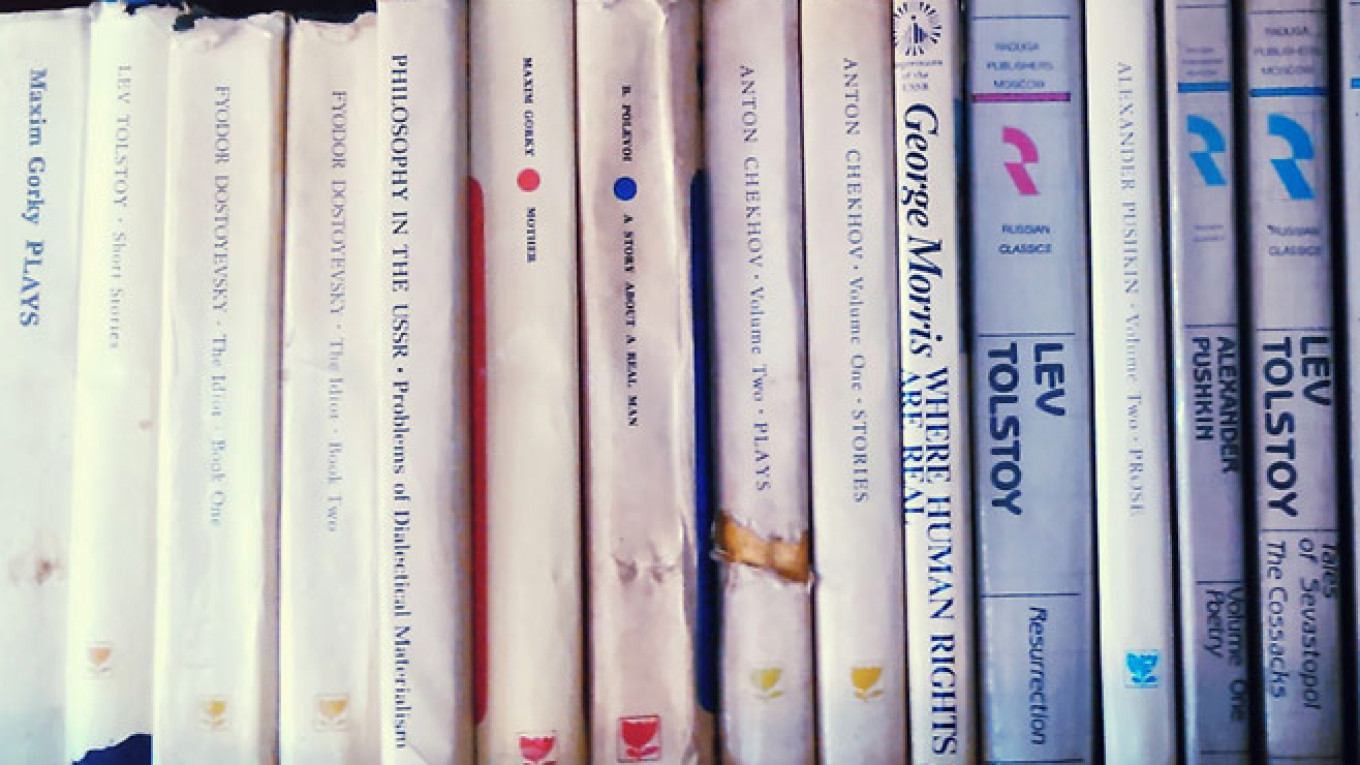

Before the liberation of the Indian economy in 1991, the same year that the Soviet Union collapsed, India and the U.S.S.R. often sided up to each other. While Indian movies in Hindi were hugely popular in Russia, translations of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Pushkin poured into India. At least a few generations of Indians from the 1960s onwards grew up reading Russian literature, not least because these books were sold cheaper than others in the market. The books of the Soviet Union were almost always hard-bound, beautifully illustrated and with the prettiest covers. I remember, as I write this, the swirling calligraphy of the P in Pushkin's "The Captain's Daughter" and the little house, tree-clad and mysterious, on the jacket of Tolstoy's "Childhood," "Boyhood," "Youth."

A generation of '80s children, those who knew little of socialism in their childhoods and went on awkwardly to embrace the excesses of capitalism, has taken to the Internet to talk about these books. I hadn't known how strong the fanbase was until I wrote a blog post about my grandfather's collection. I continue to be inundated with offers to buy my inventory at whatever price I asked for.

Every new e-mail sparks a little of the interest again to read up on the history of these books. The Internet throws up some tidbits but it doesn't tell me what I want to really know.

It tells me that the Foreign Language Publishing House (FLPH) was started to centralize all titles meant for non-Soviet readers. They published books on how progressive the U.S.S.R. was and how happy its working class, as well as early literature. Sometime in the 1960s, or in 1931 — depending on which source you want to rely on — the FLPH became Progress Publishers with the Sputnik satellite on one half of its logo and the Russian letter for progress on the other half.

The Russian book covers charmed a generation of young Indian readers.

The Internet tells me this, without any specifics. It doesn't, for instance, tell me the first names of Babkov, Smirnov, Glushkov, Maron and others — scientists and engineers at government institutes and universities who wrote manuals and textbooks on things like airport engineering, heat and mass transfer, radio measurements and the like. My ambition to be an astrophysicist, before I began to dread the physics part in high school, was fueled by a small blue book called "Space Adventures in your Home" by F. Rabiza. I wonder who Rabiza was; none of the many fan sites for Soviet books say that. I have to be satisfied with an initial before these surnames. Author bios were probably not important in the service of the motherland.

Navakarnataka Publications in Karnataka, my home state, who were supplied with hundreds of thousands of books in every genre, sold a wholesome image of the Soviet Union for Rs 5, Rs 10, or Rs 50 for a really fat book. Still much less than a full dollar. Some stray copies creep into the second-hand book stores now and then, selling like hot tea in a park on a cold day, often at three to four times the original price. They call them collectibles, these days.

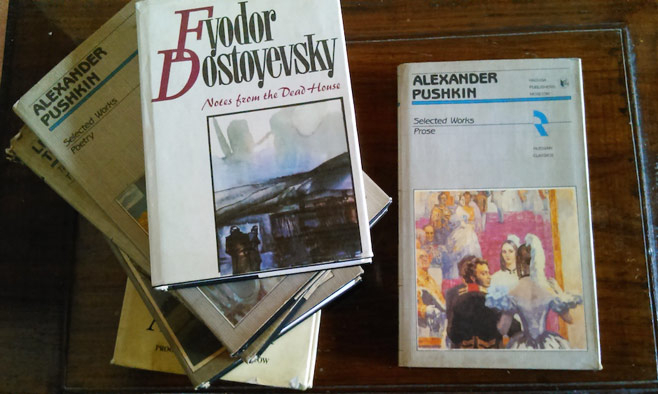

My copy of "Mother" was possibly a Progress edition, I forget now. Most of the titles grandfather owned, and the ones I continue to collect, are either Progress, or Raduga. Each prettier than the next. One has Pushkin looking over his shoulder, a tall lady on his arm. The other has Tolstoy, a much older Tolstoy, frowning, with a long, white beard. A young Chekhov looks handsome, serious and intense. Pushkin again, leaning against a pillar and staring out casually, one leg up against the pillar. A blurry structure, gray, fluid, befitting for Dostoevsky's "Notes From a Dead House."

Apparently, most of the works were available in several Indian languages. I only read them in English. I wonder who the translators were. I wonder a lot of things. The Internet hasn't bothered digging up too much .

The 1980s were when I discovered and grew up with books that made names like Boris and Sasha and Nadya and Tatyana as relatable as Rama and Sita and Arjuna from the Indian epics . They seem like fabulous years, seen through the eyes of wistfulness for the good ol' days and simpler times. Russian writers, and by extension, the Soviet Union, seemed exotically foreign and thus especially intriguing. But perhaps more importantly for me, these books were my connection to my grandfather. Perhaps it was through these that I came to relate to a man who in his own way was the rebel I would turn out to be — left leaning, liberal — in a household and a community that insisted on voting Right.

Or maybe I don't really want to know. The invitation to imagine your own stories and endings is what lends timelessness to a work of literature after all.

This article first appeared in The Calvert Journal, a guide to the new east.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.