In a move that caught both political analysts and Euromaidan activists off guard, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko recently appointed former Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili governor of the Odessa region.

Saakashvili is a polarizing figure. He is under criminal indictment in Georgia, accused of abusing his power and using excessive force against demonstrators during his tenure as Georgia's leader. Saakashvili also led Georgia into a devastating war with Russia in 2008, and has been outspoken in his criticism of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Odessa is no ordinary region. According to Nicolai Petro, a scholar of Russian politics at the University of Rhode Island who now lives in Odessa, many in Odessa still identify with Russian culture and do not see Russia as their enemy.

The data backs this up. While the majority of Ukraine has rallied behind the Maidan movement, according to a recent survey commissioned by The Washington Post, Odessa remains split between pro- and anti-Maidan sentiments. Injecting an enemy of Russia into what remains a volatile region is therefore a calculated risk.

Given the risks, two questions come to mind: What accounts for Poroshenko's decision to move Saakashvili to Odessa — and is this a smart move or a disaster in the making?

Poroshenko's motives seem guided by a number of factors. First, Ukraine believes it is at war with Russia, and Putin has made clear over the years his distaste for Saakashvili. Appointing the former Georgian president as governor of a high-profile region allows Poroshenko to tweak the Russian bear's nose.

Second, Saakashvili's appointment means Poroshenko now has an ally in Odessa. The previous governor, Ihor Palytsia, was an ally of Ukraine's leading oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky. Kolomoisky is a controversial figure within Ukraine. He funds a number of the country's private military battalions, and has not hesitated to use these to promote his own interests as well as Ukraine's.

When Kolomoisky recently showed up at the headquarters of state-owned Ukrnafta with armed men in combat fatigues after a close ally of his was fired as CEO, Poroshenko fired him from his position as governor of the Dnipropetrovsk region.

While Kolomoisky remains ostensibly loyal to Kiev, bad blood remains. Kolomoisky is unlikely to disappear from the scene, and Odessa is still a key playing field for him due to his ownership of Ukraine's largest oil refinery in the region. Replacing a Kolomoisky ally in a critical region with one of his own therefore makes perfect sense for Poroshenko.

Third, Poroshenko undoubtedly admires the changes Saakashvili implemented early in his tenure as Georgia's president. Upon assuming office, Saakashvili famously fired all 30,000 of Georgia's notoriously corrupt traffic police.

Saakashvili also implemented a heavy dose of market reforms, focusing on a sweeping deregulatory program that kick-started Georgia's economy. Georgia is now 15th on the World Bank's Ease of Doing Business index — well ahead of Ukraine, which is way down at 96th. With Ukrainians hungry for results and the government's popularity falling, Poroshenko is counting on Saakashvili duplicating his Georgian success in Odessa.

There have also been numerous reports that if Saakashvili can demonstrate some quick successes in Odessa, Poroshenko could even elevate him to prime minister. Poroshenko and Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk cooperate tactically, but are not exactly the best of friends.

After Yatsenyuk's government was recently accused of corruption, a deputy representing Poroshenko's party in Ukraine's parliament initiated a petition and rally demanding Yatsenyuk be removed from his post. If Saakashvili supercharges reforms while also providing Poroshenko an excuse to dump Yatsenyuk, Poroshenko could achieve the political equivalent of a double bank shot in pool.

Saakashvili's appointment may also be tied to the developing — and potentially explosive —geopolitical status of Moldova's self-proclaimed republic of Transdnestr, directly to the west of Odessa. Two weeks ago, Ukraine's parliament terminated a number of military cooperation agreements with Russia. One of these was an agreement allowing Russian troops and supplies to transit Ukrainian territory to reach Russian "peacekeepers" in Transdnestr.

Ukraine also recently closed checkpoints through which goods are transported to and from Transdnestr. Given that Moldova is also making it difficult for Russian goods or supplies to reach Transdnestr, the strip of land is now effectively blockaded.

Russia can theoretically still supply the territory by air — but here's where things get even more dicey. Russian planes would need to fly over Ukrainian territory, but Kiev has warned Moscow not to try establishing an "air bridge" to Transdnestr.

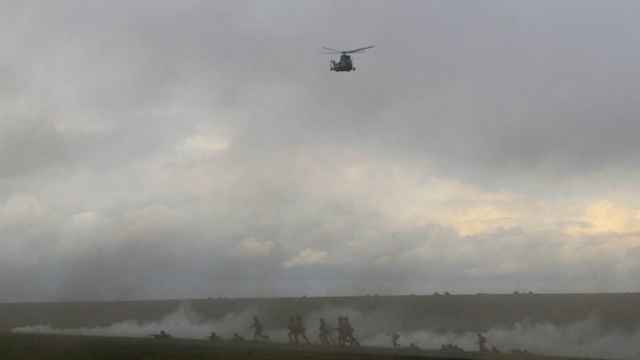

According to some media reports, to make clear to the Russians that their transit corridor is closed, the Ukrainian military has deployed extra S-300 air defense missiles near Odessa that could theoretically shoot down Russian supply planes.

What does all of this have to do with Saakashvili? According to Petro, "Saakashvili comes in handy because of his experience with a similar situation in South Ossetia, and his effective manipulation of the international media before and during the Georgian attack."

If Russia pours more weapons across the border and allows its proxies to seize additional territory in the Donbass, Kiev might redouble its efforts to coax the West into playing a more active role in its conflict. The ultimate endgame in this scenario could be an attempt by Kiev to provoke a substantial Russian attack against their forces, with the hope that NATO forces might be drawn in.

To be clear, this last scenario is unlikely. Although Ukrainian nationalism has skyrocketed due to the war in the Donbass, Poroshenko has largely managed the crisis with moderation. Poroshenko wants economic and political success stories, and if Saakashvili succeeds in Odessa, the appointment could well be seen as a stroke of genius.

Josh Cohen is a former USAID project officer involved in managing economic reform projects in the former Soviet Union. He contributes to a number of foreign policy-focused media outlets and tweets at @jkc_in_dc

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.