As often happens after the State Duma passes a new law, Russia's business community experiences a kind of quiet horror. They do not know what the future holds after June 1, or how they will manage. Each rumor is worse than the one before and shakes businesspeople by forcing them to estimate impending losses and unexpected expenses that were not included in anyone's business plans for the year.

In short, it is more of the same old thing for Russia. This method of acting first and thinking later characterizes not only the State Duma. It is a habit described in politically correct terms as "the poor quality of public administration."

Duma deputies have decided to further regulate the sale of alcoholic beverages — and to do so midyear and without adequate warning. Starting June 1, an amendment to a 1995 law will come into force that will lower the threshold for products subject to state registration from those containing 1.5 percent ethyl alcohol to those with only 0.5 percent.

When more than 0.5 percent, the manufacturer must install a Unified State Automated Information System and the retailer must obtain a license to sell the product. The other option is for the producer to change the ethyl alcohol content of the drink, but that requires greater investment.

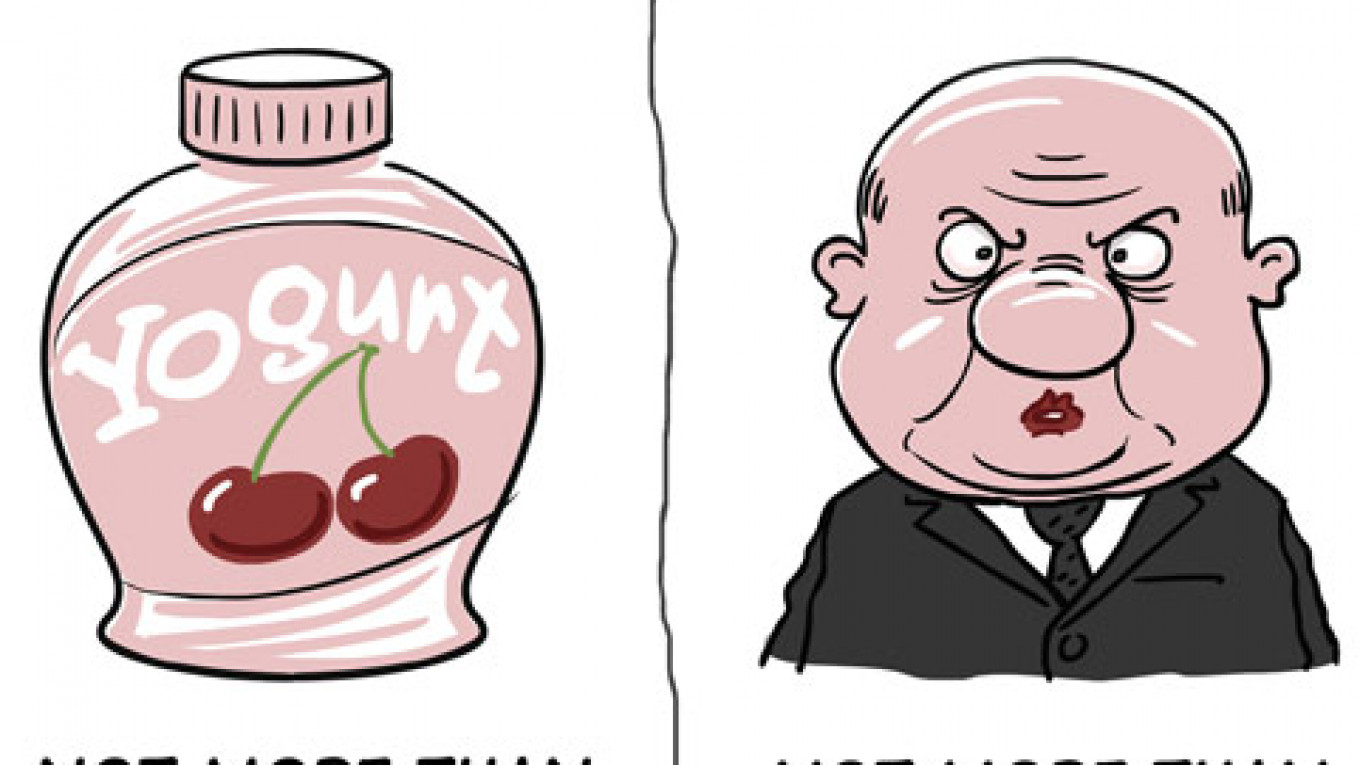

Now, only days before the amendments go into force, nobody affected by the law knows how the authorities will apply it in practice. If the law is interpreted literally, it would ban a whole range of products that have no connection whatsoever to alcoholic beverages: fruity yogurt, laundry detergent, dish soap, household cleaners, air fresheners, glues, shoe polish, furniture polish, insect repellents, wet wipes and even deodorant. Just as summer begins, the country could find itself without deodorant!

Cosmetics producers also have no idea which creams, pastes and ointments will fall under the law and which will not. They write letters to Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Khloponin asking him to elucidate — as if he knew what legislators had in mind.

Likewise, nobody knows what to do about products that were already manufactured or imported and now stand on store shelves across the country. The law says nothing about it. In such cases, retailers must prepare to bribe inspectors who can interpret the law however they want.

Russia sells approximately $200 million to $250 million annually in cosmetics and household products with an alcohol content of from 0.5 percent to 1.5 percent. Many such product labels now read: "Contains less than 1 percent alcohol," and reportedly even the manufacturers do not know the exact figure.

Now all those labels will have to be reprinted at the manufacturer's expense. Russian perfumers estimate the cost of that procedure alone at 2.5 million ($49,000) rubles per company.

At the same time, it is a total mystery as to why lawmakers suddenly decided to lower the threshold from 1.5 percent to 0.5 percent. Did they suppose it would solve the problem of public drunkenness? I have seen no clear justification for the amendments anywhere.

Lawmakers apparently took no interest in learning how the law would work in practice or what losses it would cause to Russian manufacturers. And they do this at a time when leaders are hailing the benefits of domestically produced products in the face of sanctions, and when officials are vowing not to worsen the country's already shaky investment climate.

True, Russia's parliament proved that it can produce a piece of legislation that contains very specific technical and analytical requirements, and not just another abstract political declaration of good intentions. However, as a rule, the Duma does not issue laws that are fit for immediate enforcement. In fact, at no stage of a bill's journey does it ever become "foolproof" or perfected.

Discussing the bills in the relevant committees and the option of inviting this or that expert to review them is not an effective means for guaranteeing their quality. The positive side of lobbying — that is, when representatives of pertinent industries can at least explain the issues and potential consequences involved, is not very developed in Russia.

Lobbying is misunderstood as the primitive bribing of lawmakers, although that practice has long gone out of mainstream practice in developed countries. In this sense, today's State Duma is much less subject to the influence of outside representatives of the "real world" than was the parliament of the 1990s.

That is both good and bad: the number of people and groups involved in the decision-making process is narrowing. And that is happening even as political competition within parliament has all but disappeared, when so-called "opposition" factions willingly act as puppets of the ruling party. And the smaller the number of people and differing groups involved in the debate, the lower the quality of the decisions.

By simply rubber-stamping everything that leaders hand down, parliament degrades the quality of the laws it passes. The Federation Council takes little interest in studying the laws closely. Even the president never vetoes ill-considered laws. He apparently considers the use of the veto a sign of crisis in the system, although the veto, in theory, is an integral part of the separation of powers in a normal government.

As a result, as businesses cry out, "How can we stay afloat?" the government steps in to "put out the fire" and minimize the damage caused by poorly conceived legislation, issuing pronouncements and interpretations that sporadically adds to the list of goods exempted from the regulation.

Dairy product producers and perfumers can only hope that officials will heed common sense and fix the problems. However, the whole system functions improperly. It contradicts the basis of parliamentary government: the executive branch should not, in principle, correct laws. If it does, it should assume full responsibility by issuing appropriate orders for direct action.

However, this model of dysfunctional relations between legislators and the government has become the norm in Russia. And this is reflected in the crisis affecting the entire system of government.

Starting in September, a law will go into force concerning the use of personal data in Russia, and the law on alcohol content in yogurt and toothpaste is child's play by comparison. To interpret the personal data law literally, Russia would have to prohibit the entire Internet except for state-sponsored sites — and President Vladimir Putin issued a decree to this effect recently.

Again, nobody knows how this will work in practice: they know only that it cannot work as written. The Russian people have no choice but to wait for their authorities to begin interpreting the law.

Feeling their "lack of control" over events and society, Russia's Duma deputies continue introducing new laws at a frightening rate. And because Russian laws do not carry the names of their initiators, the Russian people do not know who their legislative "heroes" are.

Senior leaders apparently believe that, in extreme cases, they can tone down bad laws, dilute them or enforce them selectively: after all, they never call legislators on the carpet for creating poorly conceived laws. But this situation only makes lawmakers want to put forward all sorts of initiatives, even if they are obviously impractical or absurd.

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.