In Ukraine, whose tumultuous 20th-century history has spilled over into a bloody battle for its 21st-century identity, every picture tells a story.

Daisy Sindelar traveled to six Ukrainian cities to talk to people about what their old family photographs say to them about who they, and their country, are today. This week, Volodymyr Balega, 60, a photographer, tells his family's story from Uzhgorod.

This article was first published by Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty as part of the My Ukraine project.

Everyone in this part of Ukraine has some Hungarian roots. My grandfather, Yuriy, always spoke Ukrainian, but his name — Kuruc — was clearly not Ukrainian. My mother remembers being sent to see her aunts in the summer, and they always spoke to her in Hungarian.

My mother grew up in a two-room farmhouse with a straw roof. My grandfather bought the house in another town and had the entire thing moved to their village, Kolchyno. They kept pigs, chickens, and livestock.

I was born in that house; I remember it perfectly. It was a perfect example of the old farmhouses you see in Transcarpathia. A few years ago, a museum even offered to buy it from our family to put it on display.

My grandmother ended up having seven children over 25 years — six boys and one girl, my mother, Varvara.

World War II was hard on my family. One of my uncles, Mykhaylo — Misha — faked his age to enter the army when he was just 16 or 17. He died a month later when he was shot by a sniper in Czechoslovakia.

Two of my older uncles, Petro and Yuriy, went on to train as Soviet intelligence agents. At least one of them studied in Moscow, but since they had grown up in this part of Ukraine, so close to so many borders and languages, they were always going to come under scrutiny.

Petro Kuruc with his daughter, nephew Yura, and mother, Brno, Czechoslovakia, 1950s.

At some point, Yuriy disappeared. Soviet agents came to Kolchyno to look for him; they suspected him of working for Hungarian intelligence. They didn't find him. He was hiding in a crawl space below the roof of the barn. But the agents interrogated my grandfather brutally, beating him with metal rods.

My grandfather didn't say a word, but he was horrified by their viciousness. I think he just couldn't believe that people could act like that. He hanged himself the same night.

Yuriy went on to work with the Czechoslovak special services. He lived in Brno and married a Polish woman; they had a son, also Yura. But it was rumored that Yuriy was providing intelligence to both the English and the Americans. This was at the start of the Cold War.

He ended up dead — thrown from the balcony of his fifth-floor apartment. His wife died under mysterious circumstances the same year. Little Yura went to live with my other uncle, Petro, who was also living in Brno and also working for the Czechoslovak special services.

Yuriy Balega in his traditional Ukrainian vyshyvanka, 1960s.

Petro was killed in the 1960s or '70s. A car drove up on the pavement and hit him as he was walking on a sidewalk. Everyone assumed it was a deliberate assassination by the Czechs, because he was considered loyal to Moscow.

My family members tracked down Yura only a few years ago. He lives outside of Prague, just leading a normal Czech life. When we first approached him, he thought we wanted to ask him for money.

My father, Yuriy, was brought up in an extremely poor family. When he came to university, he didn't even have a winter coat — that's how my mother noticed him the first time. A shivering guy eating free bread and mustard in the university cafeteria.

He ended up becoming a very respected professor of history and Ukrainian literature here in Uzhhorod. You had to be a member of the Communist Party in those days to get a high-ranking academic post, and my father was, but he still insisted on having his official picture taken wearing his Ukrainian vyshyvanka instead of a collared shirt, which was considered pretty rebellious. He got away with it somehow.

Yuriy and Varvara Balega at opposite ends of the table, with some of her students in between.

He's not a healthy person — he had his first heart attack when he was 28 years old! — but he's still alive.

My mother was a very pretty, popular woman. She was always being asked to be the witness at her friends' weddings because she had nice clothes and looked good in photographs. I have dozens of pictures of her at other people's weddings.

She became a teacher and worked with girls who lived in an orphanage. Her students really loved her a lot.

Several members of my family became alcoholics, and my mother was one of them. Eventually she had to give up her job because her drinking got out of control.

She was very good at hiding it; it took a long time for my father to find out, even though as a little boy I knew. It went on for years. She ended up divorcing my father.

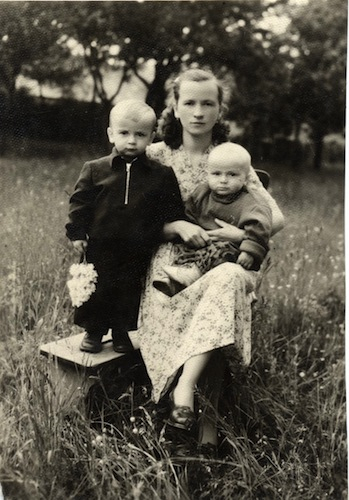

Varvara Balega with her sons Yuriy (left) and Volodymyr. Yuriy Balega is now a prominent astrophysicist and heads the Nizhny Arkhyz telescope facility in Karachayevo-Cherkessia, Russia.

My wife was studying at that time to become a doctor, and I persuaded her to focus on narcology. We helped my mother quit. She's in her 80s now and she hasn't had a drink in 30 years.

She had a whole second life. She had always had bad asthma and allergies, so finally we moved her to Crimea. The air there helped her immediately, and she ended up getting married again, to a Russian man who fell head over heels in love with her.

My father got remarried, as well. For a while, my parents had the same address — I mean, different cities but the same street name, the same house number, the same apartment number.

My mother's since moved back to Transcarpathia. Her husband died and, of course, Russia started making trouble down there. I'd go and fight them today, if I could.

Volodymyr Balega

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.