It seems that the 70th-anniversary Victory Day celebrations have robbed Russian society and political leaders of all emotional strength — strength they will definitely need.

On May 9, even very experienced television commentators were a bit flustered when, following the parade on Red Square, President Vladimir Putin laid flowers on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in the company of Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe and Abkhazian leader Raul Khadzhimba. However, the subsequent visits by German Chancellor Angela Merkel and U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry offered some consolation.

Then there was Putin's major blunder of stating that the Soviet Union had needed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact to ensure national security — a position that in the West they might call "political realism." The truth is, it has long been considered taboo among polite company to offer any justification for that agreement with Hitler's Germany. However, that is ultimately a question of etiquette.

As proof, consider how the subject of Crimea is gradually disappearing from the West's agenda with Russia. Of course, rhetorical statements continue, along with the sanctions implemented in response to the annexation, but the West is gradually coming to accept Crimea's current status as "the new normal." That is exactly what the Kremlin wanted.

At least, following Putin's meeting with Kerry, the Kremlin's statement that its U.S. partners had shown "the first signs of understanding" in their position sounded like the contented purring of a comfy and well-fed cat.

But have the same "signs of understanding" appeared in Russia? What is the condition of the country that insists that its "Crimean gambit" of one year ago and the military conflict in eastern Ukraine deserve discussion beyond the framework of The Hague Tribunal?

In order to assess the situation in Russia, let us turn to the example of Ukraine.

The Ukrainian armed forces not only did not crumble and collapse during the battles near Debaltseve, but they were transformed into a capable army. And, by the very fact of their continued activity, the Ukrainian president and parliament belie the dire predictions of some Russian experts one year ago concerning the inevitable collapse of the Ukrainian state.

But does the new Ukrainian government meet the expectations of those who 18 months ago joined the Maidan protests? Does it meet the expectations of its partners in the West who hoped for more deliberate and rapid institutional reforms? Is the current Ukrainian government really new, or do the interest groups from Donetsk, Kharkiv and Dnipropetrovsk still play the same role in it as they did two or three years ago?

Unfortunately, the answer to all three questions is "No." It is unfortunate because Russia has plenty of people who would like to see the Ukrainian experiment succeed. The Ukrainian example really serves as a model for other former Soviet republics. It could demonstrate whether large and complex countries — and not only the much smaller Baltic states — have a chance to become democratic and free market states in reality, and not only in the yearly reports of the United Nations Development Program.

It is unfortunate because the year following the events on the Maidan and the outbreak of war has shown that Ukraine has many people with a strong sense of civic responsibility, who are concerned about the fate of their country and are ready to give their lives for it and even to take on some of the functions of the state. However, it seems that they are too few in number to form the "body" of the new state. Despite all of the dreadful sacrifices, Ukraine remains much as it was before.

Of course, that might stem from a lack of understanding as to where the country should go. If so, the West has done little to fill that void. The window of opportunity for change will not remain open forever. If Ukraine was unable to pass the "maturity test" after a full year, it is possible that Kiev's partners might grow weary of its arguments that it is battling authoritarian aggression from outside, and simply turn to that authoritarian aggressor in search of solutions.

At this point, it seems more likely that Ukraine will become just one more weak, marginalized and developing country than a full-fledged candidate for rapid European integration. If so, that calls into question the prospects for other former Soviet republics to make a successful transition.

Many believed, at least in theory, that former Soviet republics making that transition would compare with average European countries. That idea seems a little strange when considering that prior to 1991, many parts of what was then the Soviet Union did not even set themselves the goal of "catching up to the West," and now they seem to have no other option.

However, those new states gained some relief from the realization that they could manipulate their socio-economic indicators and "gain points" by improving the development of their democratic institutions. They believed that the best way to achieve that task was to reject their post-Soviet purgatory and join the paradise of the "developed world."

Russia's last attempt to follow that path, undertaken by former President Dmitry Medvedev, so fully discredited the idea that it seemed that no worse example could exist. But that was until Ukraine's current conflict and the clear prospect of it joining not the "First World" but the "Third World," and having to fight a full-scale war became an added "bonus."

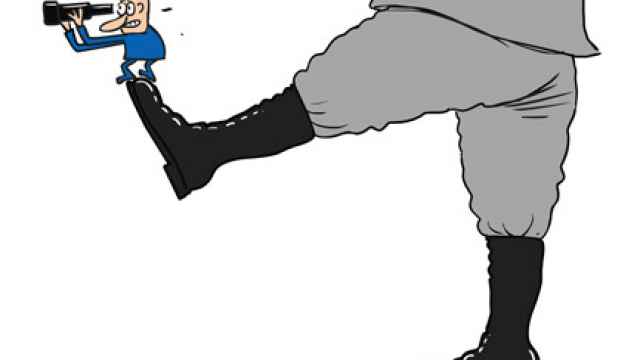

It has become clear as never before that the institutions created in the former Soviet republics during what was supposed to have been their period of transition, are nothing but imitations of the real thing. They are imitations of political pluralism, the separation of powers, an independent judiciary, parliamentary government, federation and municipalities — just like in modern Russia. It is like a souvenir mock-up of a Kalashnikov rifle: it looks real and has all the same parts, but it cannot shoot.

A phenomenon called "cargo cultures" arose on the most remote islands of Polynesia in the 20th century. After rare visits by Westerners with their aircraft and abundant "cargos" of never-before-seen goods and technologies, the natives attempted to reproduce that abundance by using earth and branches to fashion reconstructions of the airplanes they had seen.

The institutional structures in post-Soviet states, including Ukraine and Russia, recall those aircraft of earth and branches. Ukraine is now in a situation where its "airplane" of government should lift off and soar, but airplanes made of earth and branches do not fly. At such a moment, its builders cannot but wonder what went wrong.

Now is the time to think seriously about how the post-Soviet transition will proceed, before the only option left is for the entire region to become part of the "developing world" — with war thrown in as a "kicker."

As difficult as it is to believe, Russian society is increasingly desirous of understanding what really happened to this country in 1991 and why it has spent nearly the last quarter of a century building an airplane that is incapable of flight.

It is a long path from this first, dawning awareness to taking purposeful and constructive action to remedy the situation, but Russia can traverse that distance quickly. After all, nobody wants to remain part of the "developing world" forever.

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 15 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.