In Ukraine, whose tumultuous 20th-century history has spilled over into a bloody battle for its 21st-century identity, every picture tells a story.

Daisy Sindelar traveled to six Ukrainian cities to talk to people about what their old family photographs say to them about who they, and their country, are today. This week, Natalia Zubchenko, 31, an anesthesiologist, tells her family's story from Dnipropetrovsk.

This article was first published by Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty as part of the My Ukraine project.

A few years ago I became interested in my family heritage because I'm the last in my line, and because there are very few members of my family still alive.

All in all, there are really just four of us — me, my mother, my grandmother, and my mother's cousin. We're all doctors by profession.

I work as an anesthesiologist at the front-line evacuation hospital set up at the Dnipropetrovsk State Medical Academy for wounded Ukrainian troops. My husband is also an anesthesiologist; he's currently working in a field hospital.

Most of us didn't have any experience with field medicine or treating combat injuries, of course. We weren't expecting a war. It took us about two months to get up to snuff.

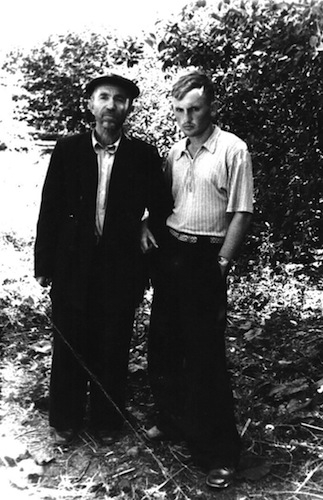

Danylo Holovakha and his son, Pavlo, in Chervone.

In Ukraine, we say we have a traditionally matriarchal society. Even in the Middle Ages, it was the groom who would come to live with the bride's family, not the other way around. It's very customary for women to work as doctors.

My grandmother, Nina, was born in the village of Chervone in Zaporizka Oblast. It was 1933, in the middle of the famine. There were five children altogether.

My great-grandparents had already been labeled as kulaks — wealthy peasants — and had their property seized. My great-grandfather, Danylo Holovakha, had owned a mill. But somehow he and my great-grandmother managed to find work during the Holodomor, and no one starved to death. They ate grass and whatever they could find to survive.

Nina Holovakha (left) with her mother and sister, 1940s.

My grandmother moved to the city around Dnipropetrovsk around 1950 to start nursing school and then medical school. She became an ob-gyn. People always thought she looked a little like the actress Vivien Leigh.

She never had any particular love for the Soviet Union. Her memory of World War II was of the German soldiers handing out candy and the Soviet ones ramming their tanks into houses.

In 1963, she was formally punished at work for speaking Ukrainian instead of Russian. But she ended up being the Communist Party boss at her hospital just the same.

Now she speaks Russian better than Ukrainian. But occasionally I can still hear the Ukrainian slip in, especially when she answers the phone.

Pavlo Holovakha (left) during military service with the Black Sea Fleet, early 1940s.

Dnipropetrovsk is a very specific city. A lot of Kremlin bosses came from here. Brezhnev was born nearby in Dniprodzerzhynsk. Leonid Kuchma, Pavlo Lazarenko, and Yulia Tymoshenko are all from here.

For a long time, it was a closed city because of the Yuzhmash ballistic missile plant. Even now, we have our own way of doing things. We don't think of ourselves as east or west. We're central.

I think Euromaidan did a very good thing for Dnipropetrovsk. If a year ago you had shown someone here a blue-and-yellow flag, I don't think it would have meant anything special to them at all. But the Maidan roused people's sense of national identity.

If the Russians had invaded and there had been no Maidan, I think the situation right now would be quite different. They might have made it to Dnipropetrovsk, or even further into Ukraine.

That said, I don't think our soldiers are getting nearly the support they need. I think there's more to this war than we can see. I only hope that when we find out the whole story, it'll be clear that our people are dying for a reason.

I've traveled quite a bit, and I used to spend a lot of time explaining that Ukraine wasn't in Africa or Asia, that it was a country next to Russia, but that it wasn't the same thing as Russia.

Now when I travel, people get really excited when they see my passport. In one country, all of the passport-control workers even passed it around, saying, "Ukraine! She's from Ukraine!"

For a while, I was worried I wasn't going to get my passport back. But it's nice to know that other people know about my country and care about what's happening here.

Natalia Zubchenko

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.