In Ukraine, whose tumultuous 20th-century history has spilled over into a bloody battle for its 21st-century identity, every picture tells a story.

Daisy Sindelar traveled to six Ukrainian cities to talk to people about what their old family photographs say to them about who they, and their country, are today. This week, Alla Husarova, 47, а journalist, tells her family's story from Kiev.

This article was first published by Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty as part of the My Ukraine project.

Nearly all of my family comes from the Vinnitsya region, mainly from small villages. Now there are buses that take you to these tiny towns directly, but it used to take hours and lots of waiting and transfers to get back and forth from Kiev.

It really felt far away. But all of Ukraine's 20th-century history touched my family in one way or another.

My maiden name is Bondarchuk. My great-grandfather, Yakov Bondarchuk, grew up as a simple village kid. But he was slightly different in that he had gone to school and learned to read and write. That wasn't the case for everyone back then.

So when the Russo-Japanese War started in 1904 and they began drafting Ukrainians, they singled out the boys who were literate to train as medical assistants. So my great-grandfather didn't fight; he worked in the surgical ward.

Lesia Babukha (bottom left) at a school celebration in Illintsi, 1925.

It was very difficult work, very emotional, seeing all those injured soldiers. Many doctors from that war became addicted to drugs or anesthesia, since they had such easy access to it. I guess my great-grandfather wasn't an exception.

He eventually was shipped back to Odessa — a horrible journey in itself — and returned to his village to become the local doctor. He got married and raised three children, including my grandfather, Ivan. But he remained addicted to drugs, and he died quite young.

My grandfather grew up to become a history teacher and a school director in the village of Bilky. He had grown up in a neighboring village, but he married a Bilky girl, my grandmother, Oleksandra Babukha. Everyone called her Lesia; I called her Babushka Sasha.

Ivan Bondarchuk as a young man.

She was the daughter of an Orthodox cleric who had been forced by Soviet authorities to renounce his vows in order to ensure that his children wouldn't be marginalized. He had 10 children who lived to adulthood, so this was a serious consideration.

My grandmother attended a school specializing in agricultural studies. She went on to teach biology, and botany was her specialty.

She knew everything about plants, and later on in life she kept an amazing garden, with all different varieties of roses and a greenhouse. Visitors were always coming just to look at the garden.

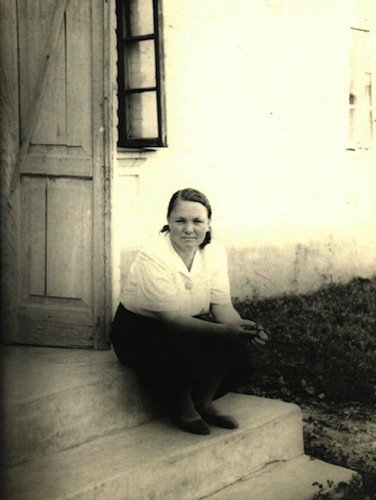

Lesia Bondarchuk, outside the Bilky schoolhouse.

My grandfather fought in World War II, as a gunner. He received a certificate of gratitude signed by Stalin for his role in destroying a German tank division somewhere in Hungary or Czechoslovakia.

My grandmother, meanwhile, remained in Bilky during the occupation. She was teaching and living in the school with my father, Valentyn, who was by then a teenager, and his sister, Taisia, who was quite small.

At some point, they had German soldiers lodging with them. One day, my grandmother became frightened because one of the soldiers was sitting and staring at Taisia, who was just 1 or 2 at the time. She was sitting on the floor, playing with a toy, and the soldier was looking at her very intently. But then he started to cry and gave her a sugar cube. He said he had a young daughter at home.

Filip Mospan and Tetyana Honchar, 1930s.

My grandmother didn't harbor any illusions about the Nazis, but she didn't suffer any particular abuse during the occupation either. Terrible things were happening to Jews in Vinnitsya, but life in Bilky was relatively quiet.

When the war was over, the Soviets allowed her to keep her job. She wasn't punished for living under occupation, like many Ukrainians were. But when she retired, she was given a tiny pension — just pennies. All those years later, they were punishing her for collaboration.

These days, it's really hard to know what was the right thing to do. It's gotten really popular to say your family fought with the partisans. But in Bilky, for example, the partisans weren't up to much of anything good. The people who simply went on living under occupation got a lot of grief, even though the country wasn't doing anything to help them. What could they do? Were they all supposed to flee?

My second set of grandparents also lived in Bilky, but they were very different. My grandfather, Filip Mospan, was from a prosperous peasant family that lost everything during dekulakization, when the Soviets forced Ukrainian farmers to give up their private property. They lost their house, their animals — everything.

My grandfather went east, to the Donbass, to find work. This was during the Holodomor, the famines, and the Donbass was one of the few places where you could find a job and get paid with food. There was a lot of effort going into industrializing the region, and my grandfather spent a few years working in a mine.

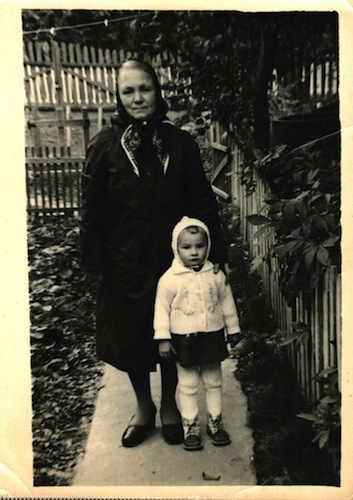

Babushka Sasha and Alla in Bilky, circa 1970.

It was during that time that he met my grandmother, Tetyana Honchar. She was the daughter of an Orthodox priest who was arrested as part of the Soviet crackdown on religious authorities. He and Tetyana's mother both ended up dying of starvation during the Holodomor.

Tetyana was just a teenager. And as the daughter of a repressed priest, she had been kicked out of school. She never made it past fourth grade. And she refused to recant, which might have helped her get back in the good graces of the authorities. The whole thing left her very bitter.

Filip and Tetyana eventually moved back to Bilky. Filip found jobs here and there, and they worked on their property constantly. That's what I remember as a little girl. With my other grandparents there were books and flowers and walks in the forest, but with them there was just physical work. And religion -- my grandmother remained deeply religious. She tried to talk to me about it, but as a Soviet child, I just found it very strange.

I lived in Bilky until I was 4. My parents were studying, so they sent me to live with Babushka Sasha. I was her first grandchild, so she loved me a lot. She took me on long walks and taught me everything she knew about plants. Even today I know a lot about nature, about trees and medicinal herbs.

We've always been a Ukrainian-speaking family. I remember coming back to Bilky at some point after I had been going to school in Kiev and I said something in Russian, to show off a little, you know — to show that I was a city kid. My grandmother put an end to that immediately.

She died when she was 95, in 2003. She had Alzheimer's for the last decade of her life. But she was always very tidy, very precise. Every night before she went to sleep, she took off her slippers and lined them up very neatly next to the bed. Right until the end.

Alla and her son, Anatoliy, who spent nearly every day at Independence Square during Euromaidan.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.