In Ukraine, whose tumultuous 20th-century history has spilled over into a bloody battle for its 21st-century identity, every picture tells a story.

Daisy Sindelar traveled to six Ukrainian cities to talk to people about what their old family photographs say to them about who they, and their country, are today. This week, Andriy Ignatov, 40, an economist, tells his family's story from Kiev.

This article was first published by Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty as part of the My Ukraine project.

My grandfather always wanted to write our genealogy. So when he died, I decided to do it for him.

I think a lot of Ukrainians are thinking about their personal history these days. We're all wondering how to deal with this legacy that's been handed to us — communism, famine, World War II, Orthodoxy. It all feels very fresh, very raw, now that Russia is waging war on us again.

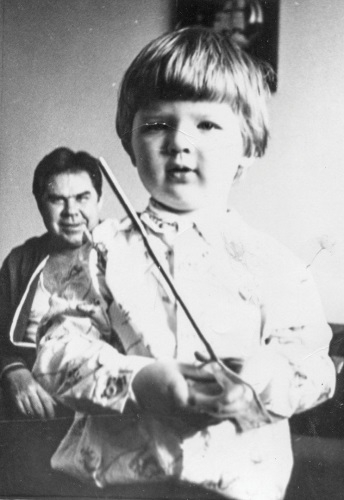

Yuriy and Andriy Ignatov, Zaporizhzhya, 1979.

In Ukraine, your hometown says a lot about who you are. Every city has its own distinct character. "Oh, you're from Vinnitsya? You must be this kind of person," etc.

My grandfather, Yuriy Ignatov, grew up in Kharkiv, and it played a big part in shaping who he was. Kharkiv was the first Bolshevik capital of Ukraine, and my grandfather was a true Soviet.

He joined the Communist Party after World War II and it really gave him education and career opportunities that he wouldn't have had otherwise. He and his wife were veterinarians, and eventually he became a fairly high-ranking agricultural official.

He wasn't a rah-rah communist — one of those people who got excited by Soviet slogans or getting their pictures taken next to statues of Lenin. He just genuinely believed the U.S.S.R. had been formed for a reason, and that it was out to achieve something important. He took it seriously.

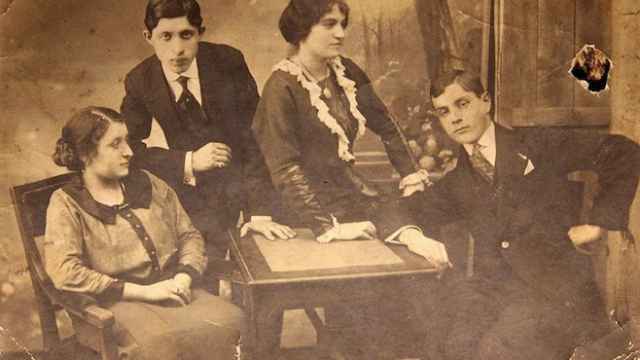

Yuriy Ignatov (seated) with his family in the outskirts of Kharkiv, 1932.

My grandfather loved to read and learn new things, and he was always ready for an argument with us kids.

I think I was his favorite, because I was the best listener. But we would always talk back. He would tell us about how great the Communists were, and we would tell him it was all bulls--t.

He never agreed with us, but he was always interested in what we had to say. I think we were like a little release valve for him. We said the things that he might have been thinking, but would never have said out loud.

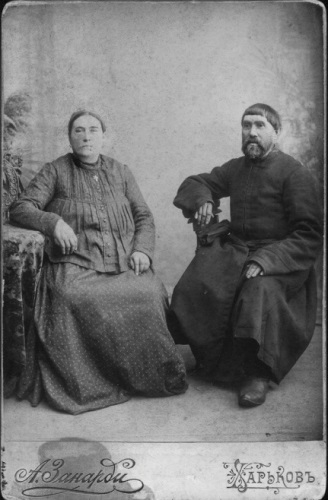

Yuriy Ignatov's maternal grandparents, Oleksandra and Tymofiy Hrinchenko, circa 1910. The couple had their house and possessions confiscated by Soviet authorities in the fall of 1930 after failing to pay tax on eight sheep. Their eldest son was later sent to a labor camp in Arkhangelsk after refusing to turn over a horse to the local kolkhoz, or collective farm.

Two of his four children died within a year of arriving in northern Russia.

For years, he denied that there had ever been a Holodomor — Stalin's man-made famine aimed at forcing Ukrainian peasants off their land and onto collective farms. This was true even though his own family had been evicted from their property during the famine. Most of his family died during the famine and World War II, but it was something he never talked about.

Towards the very end of his life, he received a letter from a cousin whose family had been exiled to Arkhangelsk in 1930 because they refused to pay a tax on their sheep. They had managed to come back to Ukraine a few years later, but it was during the famine and they ended up leaving again for good.

So all these years later, here was this cousin living in faraway Arkhangelsk who knew all about the Holodomor, talking to my grandfather who lived right in the famine zone and didn't. Or pretended not to.

I think after that, he started to acknowledge more openly that the system had a lot of problems.

Left: Yuriy Ignatov, Germany, 1946 / Right: Lidia Pryhodko, circa 1949.

My grandfather served in World War II and was injured in Kaliningrad. After the war, he was wearing his military uniform when he went to register at the veterinary institute in Kharkiv, and that's where my grandmother, Lidia Pryhodko, saw him for the first time. She said she noticed him because his medals were jingling as he walked down a flight of stairs, and she decided then and there, "That's my man."

A few years ago, someone broke into his flat and stole his medals. He was really upset about that. At that point, the Soviet Union had collapsed, Ukraine was independent, and the rules as he knew them were changing. He couldn't believe that someone would steal his World War II medals. "There should be some order!" he said.

We told him to go to the police, but he refused. He had heard so many stories about corruption, he thought the police would just accuse someone in the family of stealing the medals as a way to extort money from us.

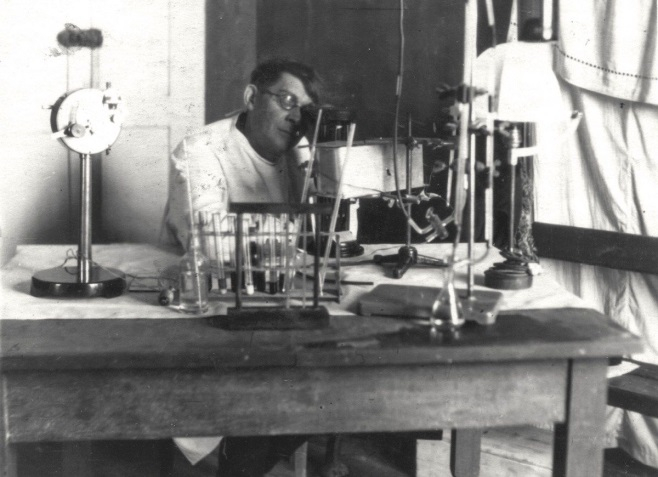

Oleksandr Ignatov in the laboratory of the Kharkiv psychiatric hospital and research institute, 1938.

There are a lot of doctors in my family, and a lot of psychiatrists.

My great-grandfather, Oleksandr Ignatov, was in charge of running the Kharkiv psychiatric institute during World War II. Communist Party members were evacuated ahead of the German advance, because they were considered at high risk of execution. My great-grandfather wasn't a Communist, so he stayed behind.

At some point, the Nazis came and executed the patients, more than 400 people. There was some speculation that my great-grandfather tried to kill himself, out of fear or despair. But we don't know if that's true. In any case, he remained in the profession for the rest of his working life.

My father is also a psychiatrist, and my maternal grandmother was as well. She was the director of the regional psychiatric clinic in Zaporizhzhya, where Crimean Tatar dissident Mustafa Dzhemilev was sent for evaluation when he was jailed in the 1970s.

I always believed that Ukraine didn't use punitive psychiatry the way that Russia did. Or perhaps we did, but only in Kyiv. But these are the kinds of questions we need to be asking ourselves now.

Yuriy Ignatov (second from right), Zaporizka Oblast, 1965.

Despite being a real Soviet man, my grandfather was also an intellectual and very proud of being Ukrainian. He saw Ukraine as the engine that kept the whole U.S.S.R. running.

Occasionally you could hear him joke about how incompetent Moscow bureaucrats were, or grumble about how unfair it was that Ukraine produced so much grain and metal for everyone else and got so little in return.

And as he got older, he began to see that his children weren't enjoying the same benefits that he had. Factory workers were making more than doctors. Life wasn't getting better.

He was also intolerant of other types of Ukrainians — he didn't like Poles or Tatars at all. Publicly, he subscribed to the Soviet "brotherhood of nations," but in reality he thought Sovietized, Russian-speaking Ukrainians were superior to everyone else.

He was 87 when he died in 2013. A few months before that, he told me there were rumors in his veterans' group that Russia was going to try to restore the Soviet Union. He thought that would be a good thing.

But I think it would have killed him to see what's going on now, watching Russia invade Ukraine, seeing what these terrorists are doing to us now.

Andriy Ignatov

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.