As I sat eating lunch with a friend in a cafe in central Moscow, a city bus drove past emblazoned with the logo of the Russian Military-Historical Society.

A huge double-headed eagle over a St. George ribbon stood against a yellow background covering the side of the bus. Over the rear door I read the name of the corporate sponsor, along with a stylized hammer and sickle — the main symbol of the Soviet Union. Even the bus itself was named in honor of Konstantin Rokossovsky, a marshal of the Soviet Union and famed World War II commander.

During these spring days before the 70th anniversary of the victory over Nazi Germany, the focus on historical symbols reaches such a fever pitch that every other social or political question fades into unimportance. There was a similar mood in the run-up to previous Victory Day celebrations as well, but something is different this time.

I was in the second grade in 1985 when the Soviet Union celebrated the 40th anniversary of the war victory. Those who were 20 years old when the war ended were 60 that year, and they were thrilled to see a great number of their fellow veterans.

Back then, the celebration was simple and straightforward. People invested less emotion in celebrating the defeat of the enemy than in harboring a clear understanding of the significance of those events and rejoicing that the horrendous nightmare was behind them.

Now, 30 years later, those who were 20 at war's end are now 90. Considering that the average lifespan in Russia is just over 70 years, most of those men and women are no longer with us. President Vladimir Putin's heartfelt words that the veterans are still dear to us were seemingly directed at those many thousands who were still alive in 1985, though in fact only a tiny handful of very old veterans remain to hear them now.

Unfortunately, not all of those survivors feel that the government cares for them as much as Putin claims to. Only a few days ago, in the Central Museum of the Great Patriotic War in Moscow, a couple of extremely aged men stood before a diorama depicting the storming of Berlin.

Both were old enough to have been participants in those events in the spring of 1945, and they were discussing the "dark side" that gets lost in all the hoopla of victory celebrations. "We were the ones that defeated the Germans," one said, "and yet look how they live now compared to how we live!"

One of the glass cases displayed the school notebooks of boys whose lives had been torn apart by the war. They were no different from mine at the same age. Nearby lay a letter written from the front in 1943 by an aircraft squadron commander and addressed to people in Moscow he had never met.

It explained that the airplane of their relative, a young lieutenant, had been shot down, that he had not managed to eject with his parachute, and that his friends pulled his body out of the burning wreckage of the crashed plane.

These are not faceless granite monuments, but the living traces of the huge wound that war inflicted on the country. My family, my wife's family and the families of my peers all have similar letters. Those memories are truly one of the ways in which millions of separate families are transformed into a cohesive nation.

The problem is that we are the last generation for whom all of that still matters. When the Soviet Union celebrated the 40th anniversary of that victory in 1985, I still had a great-grandfather who told me his own war stories and the stories of a dozen of our relatives.

But there will be no one to tell those stories firsthand to my children, and the memories of that war will gradually die out.

Now let's look at this from the point of view of the government. They know that people of my generation still get goose bumps whenever they hear or read such letters from the front. And, unfortunately, it is also the only thing those authorities know of that unites at least part of Russian society.

Back in 1985, Moscow leaders might have overestimated the strength of the bonds holding the Soviet Union together, but never for a moment did they imagine that the memory of the war victory was the only thing holding the country together. At least they had the Soviet Constitution, socialism and the role that the Soviet Union played in the world.

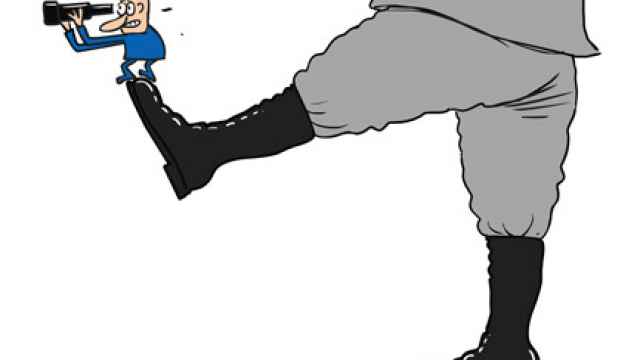

However, that political consensus, coherent purpose and even that real or imaginary role in world affairs no longer remains in the deck of cards that their resourceful heirs play today. That is why the card of war victory has taken on the value of the joker and why the number of strange combinations in which the authorities attempt to play that card is growing.

That is also why Moscow has erected an aesthetically controversial monument to the soldiers and officers of World War I near the memorial to the Soviet victory in the Great Patriotic War, and why exhibitions featuring Russian heroes of both wars have sprung up in a number of war museums.

Kremlin spin doctors are attempting to create a symbolic structure in which World War I and the Great Patriotic War are part of a single history linking the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union and modern Russia.

Marshal Rokossovsky, who died in 1968, would probably be surprised to see his name alongside a black double-headed eagle. But he fought in World War I and became a Knight of St. George, the highest honor for a soldier in old Russia. That really is a single history and the idea of recasting it as a unified narrative has some merit.

For now, the public agrees on only one thing: the significance of Victory Day on May 9. For some, the empire is the emblem of Russia's lost future, and for others, the Soviet Union is a shattered ideal. But both groups agree that those who would hurriedly and sloppily rewrite history are usurpers and speculators — no matter how high Putin's popularity ratings might be.

The Russian people know perfectly well that they never gave their consent for the current configuration of political power, and that is a huge problem for those who call themselves "conservatives."

That has forced "conservatives" to dream up a fictitious set of quasi-historical values they are supposedly defending, when in fact they are only "conserving" their own hold on power. This country's history becomes a tool for manipulation in their hands. Worse, "conservatism" based on lies cannot but eventually degenerate into fanatical dogmas like those promulgated by Adolf Hitler.

Reading the recently published correspondence of several Kremlin administration officials creates the impression that such a risk does not bother them at all. Why not generate some chatter about the Nazis and socialism, they essentially argue, so as to distract the people from their problems and the real reasons for them?

When that bus named in honor of Konstantin Rokossovsky rolled past, I turned to my friend — who had spent half his life teaching history to schoolchildren — and asked why the authorities always cite German history up to 1939, but never consider the Germany of 1945 or 1946.

"I think they want to be like Hitler was in 1933 and simultaneously like Stalin was in 1945," he said. In my opinion, that answer is a brilliant explanation of the doublethink plaguing the Russian authorities.

When you have "weapons of mass retaliation" at your disposal, along with millions of adoring citizens willing to see their state terrorize the world as the only way out of the mess that leaders have gotten them into over the past 25 years, the temptation to escalate the conflict must be very great.

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 15 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.