Why does it already seem certain that former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has no chance of winning her second presidential bid? Commentators have offered countless explanations — everything from her previous political defeats, the compromising information about her that has accumulated over her decades in the public eye, as well as the fact that she managed to lose to Barack Obama in 2008 despite going into that race as the favorite.

But there is a far simpler explanation: Hillary Rodham Clinton is not "likable." As with other heavy-duty intellectuals or aloof administrators who feel they must descend to the level of the "common people" in order to win their approval and cooperation, Clinton wears a smile that is coldly calculated to create the impression of a pleasant person.

It does not. A person has to be born "likable." It comes from your genes, not your schooling. Of course, you can develop and hone any skill, but people always sense the difference between sincerity and insincerity.

With the advent of television and televised debates as a standard component of presidential election campaigns, voter demand has grown for candidates who come across as accessible and personally appealing.

And with Internet exposure only intensifying that immediacy, candidates in national races have become as familiar as a close aunt or uncle — almost like members of the family.

And what is our expectation for our aunts and uncles? They should be likable. Sure, their place of employment, education, experience and ability to help us in life are all important. But the factor that most determines the nature and intensity of our relationship with them is whether or not they are truly likable.

However many fine qualities she might possess, Hillary Clinton does not come across as especially pleasant or likable. The problem is that all modern U.S. presidents must have that character trait. Former U.S. Presidents John Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Jimmy Carter as the face of the "New South" — as well as President Barack Obama — all had or have that quality.

If you are not likable — even if you are as brilliant as former U.S. Vice President Al Gore or have great political experience like former U.S. Presidents Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon and George H.W. Bush — you can only end up in the Oval Office thanks to personal patronage or plain luck.

The time has passed when career politicians who have built up their skills in the executive branch can necessarily make the transition to big-time politics based on their résumés. It now seems anachronistic for vice presidents to become president, as both Richard Nixon and George H.W. Bush once did.

By the way, a perfect illustration of my thesis is the presidential election campaign that George H.W. Bush ran against Ronald Reagan in 1979-80, during which he travelled more than 250,000 miles and made 850 appearances.

A candidate can have the world's best political platform, outstanding experience in public administration and great party lobbyists in their corner, but if they are not "likable," their destiny is to travel from one lackluster event to another while their opponent with a winning smile and charisma gathers enormous crowds of supporters wherever they go.

To win in today's elections, a candidate should come across as a warm person whom ordinary voters would be happy to invite over for a family dinner, someone with whom they would like to pass the time in pleasant conversation. That is why John Kennedy won and why his brother, Robert, was on his way to defeating Nixon at the time of his assassination.

The visual media — and especially live television — have added a new dimension to politics.

Voters often make their choice based more on a candidate's personality rather than on their abstract professional talents. That is how Ronald Reagan defeated his opponent and won the hearts of the people.

Now, any time a candidate appears on the screen of a television, tablet or smart phone, he or she engages in a form of personal dialogue with voters. That makes a sense of humor and an easygoing manner more important than the content of the message.

Hillary Clinton is of the generation of administrator politicians. She is more like a schoolteacher than a garrulous uncle. Her political style more resembles Lyndon Johnson than Barack Obama.

Her campaign consultants are doubtless aware of this problem. Even the fact that they launched her campaign with pre-recorded commercials rather than a live announcement demonstrates that they will limit her direct communication with voters as much as possible, probably finding more appealing public figures to speak on her behalf.

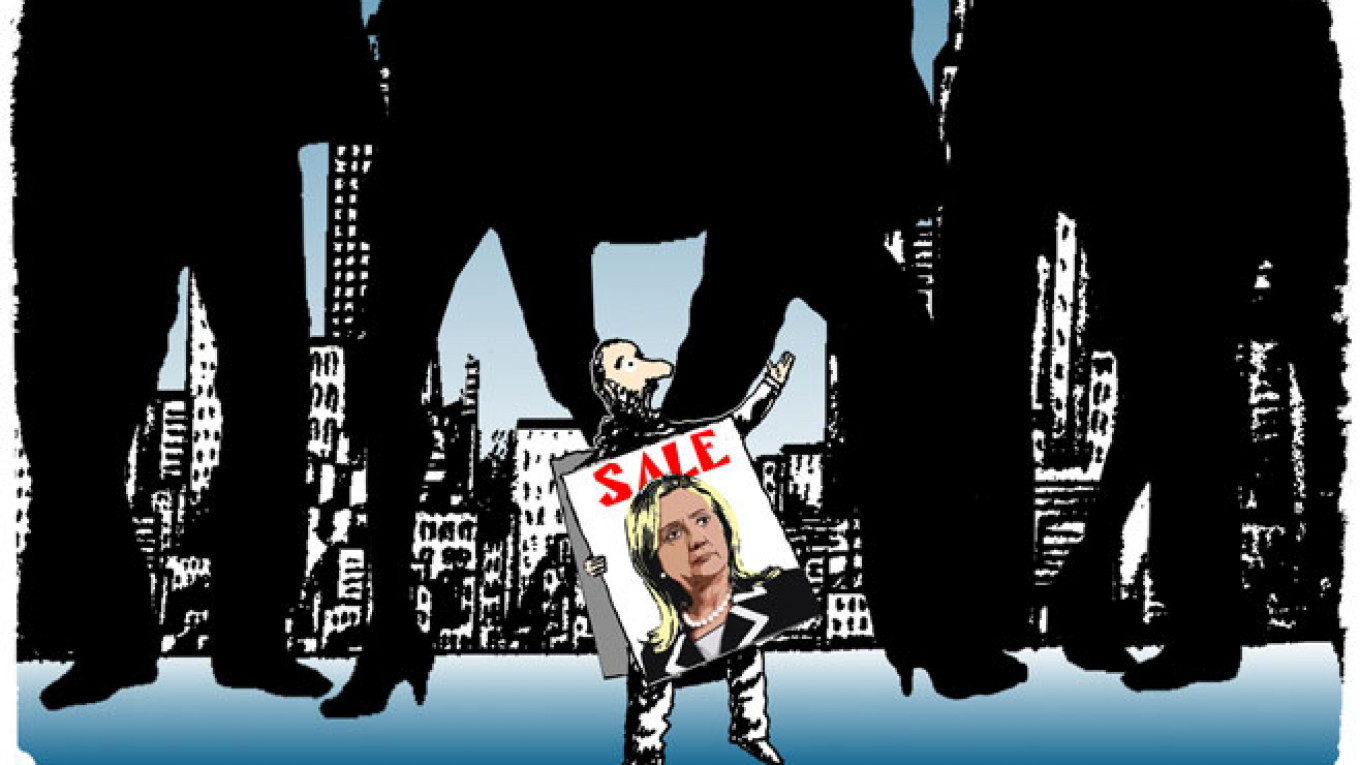

An unlikable uncle may try to buy his way in the family circle by piling his relatives with presents. The prospect of a billion-dollar Clinton campaign means she's going to do the shopping as well.

Can a candidate who is more like Nixon in a skirt win the presidency in a country spoiled by the likes of Kennedy, Reagan, Carter, Bill Clinton and Obama? Will the dozens, even hundreds of "likable" people that Hillary Clinton might pay to support her candidacy compensate for her own lack of personal charm? I doubt it.

Hillary Clinton would stand a better chance if she found some relatively unknown but bright, charming and upbeat young politician and then ran as his or her highly skilled and experienced vice president — as Nixon was for former U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower and George H.W. Bush was for Ronald Reagan. Such a team would be unbeatable.

Gleb Kuznetsov is a Moscow-based political commentator.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.