Should Hillary Clinton — who once compared Russian President Vladimir Putin to Adolf Hitler — become the next U.S. president, no improvement should be expected in U.S.-Russian relations, political analysts said Monday.

Relations between the two countries suffer as the result of a fundamental conflict in which Russia is fighting for a bigger role in global affairs than it has been allocated by the United States, and from what Clinton has said and done in the past, it is unlikely she would yield as an American leader, Russian pundits agreed.

"Regardless of whether Hillary wins or loses, we are in the midst of a fundamental and serious conflict," said Dmitry Trenin, head of the Carnegie Moscow Center think tank. "My main hope is that it will remain cold and not turn hot," he said.

Clinton, who announced her bid Sunday to succeed Barack Obama as the 45th — and first female — U.S. president, has said in the past that Putin's Russia must be contained and checked. Putin, in turn, has repeatedly said that the United States seeks to thwart Russia's legitimate interests abroad and destabilize the political situation inside the country.

No Love Lost

During the last eight years since she became one of the most powerful women in the world as U.S. Secretary of State during Obama's first term, Clinton has also been one of Putin's fiercest critics.

Most recently — in February — she said European governments were "too wimpy" in dealing with Putin, the CNN television channel cited London Mayor Boris Johnson as saying.

"Her general anxiety was that Putin, if unchallenged and unchecked, would continue to expand his influence in the perimeter of what was the Soviet Union. She spoke of alarm in Estonia and the Baltic states. I was very, very struck by that," Johnson told CNN, describing his meeting with Clinton in New York.

Clinton's urge to consolidate European leaders against Putin is no surprise, as Europe is one of two principal challenges to the U.S. policy of containing Russia, according to Pavel Zolotaryov, deputy head of the Moscow-based Institute for U.S. and Canadian Studies think tank.

"The two main challenges to U.S. policy on Russia are Europe, which is prone to divisions, and China, which could offer Russia some economic relief. Whoever is in the White House will act according to these premises," Zolotaryov said in a phone interview.

Trading Barbs

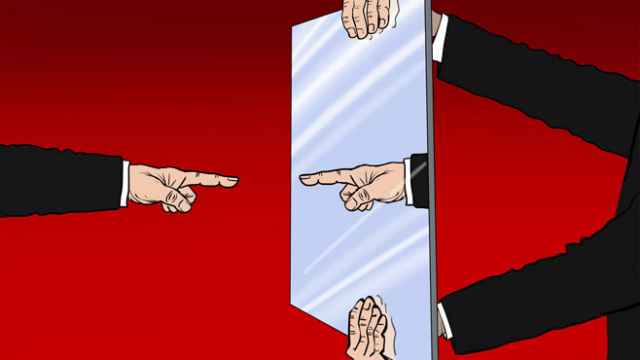

Some of Clinton's indirect exchanges with Putin have taken on a personal tone.

At the beginning of 2008, before she lost out on the presidential nomination from the Democratic Party to Obama, Clinton told the audience during a campaign event that Putin, as a former KGB agent, "doesn't have a soul," referring to a well-known remark made by George W. Bush upon first meeting Putin in 2001 when the U.S. president said, "I was able to get a sense of his soul."

A month later, Putin said in answer to a journalist's question during a news conference that "a statesman must at least have a head."

At the end of 2011, Putin accused Clinton and the State Department she headed at the time of inciting anti-Kremlin unrest over the State Duma elections that were condemned as fraudulent by observers.

The mass protests signaled the end of the so-called "reset" of relations between Russia and the United States, a broad effort by Obama and President Dmitry Medvedev to give the ties between the two countries a fresh start.

Last March, as Russian troops fanned out over the Crimean Peninsula shortly before Moscow announced its decision to annex the territory from Ukraine, Clinton said that Putin's actions there were akin to Hitler's moves to occupy neighboring territories in the 1930s, which the Nazi leader justified as necessary to protect German people there.

On that occasion, Putin said Clinton was a weak woman.

"Ms. Clinton has never been too graceful in her statements. Still, we always met afterward and had cordial conversations at various international events. I think even in this case we could reach an agreement. When people push boundaries too far, it's not because they are strong, but because they are weak. But perhaps weakness is not the worst quality in a woman," Putin said, responding to a question from a French journalist.

Reacting in turn to that statement, Clinton said Putin was "not the first male leader who has made a sexist comment like that."

Speaking on CNN back in July, Clinton said that Putin "acts bored and dismissive" and "as though it's a burden on him to be in conversations with other world leaders.

"I would be delighted if the U.S. could have a positive relationship with Russia and I would be thrilled if Russian people, who are so capable, had a normal country that they could chart a different future. I think that would be next to impossible at least for the short term with Putin," she said.

Most recently, at a public event in January, Clinton did a comic impression of Putin, joking about the ease with which he swapped roles with Medvedev when Putin returned to the presidency, and contrasting the procedure with hard-fought U.S. elections.

Obligatory Statements

According to Alexander Konovalov, head of the Institute for Strategic Assessments, a Moscow think tank, Clinton has to be tough on Putin in order to prove that she will defend national interests.

"The democrats always feel obliged to demonstrate that they can be tough. In Clinton's case this is exacerbated by the fact that Obama has been accused of being too dovish with Putin," he said in a phone interview.

Strongly worded emotive criticism of Putin has become the norm in the West and Clinton has to demonstrate that she can stand up to such a difficult leader, Trenin said.

"It has become popular in the U.S. to criticize political leaders for being weak in their dealings with Putin, so Clinton is simply responding to the agenda here," he said, adding that any personal relationship between the two would likely be professional.

Contact the author at i.nechepurenko@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.