As the Kremlin's propaganda machine shifts into high gear in the run-up to Victory Day on May 9, it is casting the 70th anniversary as a celebration of the Soviet Union's victory in the Great Patriotic War, and by no means of the Allied victory in World War II.

Russians believe they are celebrating something substantially different on May 9 than what the Allied countries celebrate on May 8 — although it was for purely technical reasons that the official message from Berlin that the war had ended reached the Allies on May 8, 1945, and reached Moscow when it was already May 9 there.

Russians consider their Great Patriotic War as a thing apart from World War II, and anyone who suggests otherwise risks getting branded as a falsifier of history.

Commentators love to point out the irony of Russians celebrating the victory over Nazi Germany even while driving about in expensive German cars. But the irony runs even deeper: As Russian society takes great pride in its victory over National Socialism, it is gradually moving toward fascism itself.

The authorities have brought criminal charges against the owner of a store in the center of Moscow who sold collectible figurines of World War II German soldiers and officers. Actually, a few years ago in approximately the same location, I bought a set of figures made in Russia that contained a couple of model horses requiring assembly and painting.

I hope nobody will interpret this as a confession of treason, but those horses were part of a Cossack unit that the Germans had created in the occupied Don in southern Russia. Those Cossacks wore Wehrmacht uniforms, and it is a little scary to think they could now be used as a dangerous piece of evidence against me.

I think the scandal over World War II figurines is not so much proof that Russian society is marching toward fascism or that the authorities want to control what we do and think in our free time as it is a manifestation of cretinism on the part of a few overly zealous functionaries.

I do not think the threat of fascism is found in that toy store on Okhotny Ryad. The real threat stems from Russians' selective memory and their lack of knowledge about the nature of fascism. More Russians have read "Mein Kampf" than, for example, "The Origins of Totalitarianism" by Hannah Arendt.

Soviet society gained most of its information on the structure of Nazi Germany from a 1973 television series by Tatyana Lioznova about the adventures of an imaginary Soviet spy in the Führer's headquarters during the final days of the war. Since our earliest school days, it was drilled into our heads that the Soviet Union defeated Nazism, but even our teachers did not really know the nature of this thing that the Red Army had defeated.

This basic lack of knowledge automatically meant that Russians had no clear idea of what to look out for or which tendencies to avoid when, overnight, they found themselves bereft of the Soviet Union and full of bitterness, humiliation, frustration and uncertainty about the future.

The political tools that enabled the Nazis to gain power included national ambition, nostalgia, resentment, susceptibility to propaganda and the willingness to act aggressively — traits that are likely to be found in any collapsing empire.

And those in Russia who are employing the same tools now are probably well aware who used them last. But those whom the Moscow authorities are manipulating with those tools might not be aware of their origins, never having learned it in school — despite the decades-old cult of worshiping their ancestors for defeating Nazism.

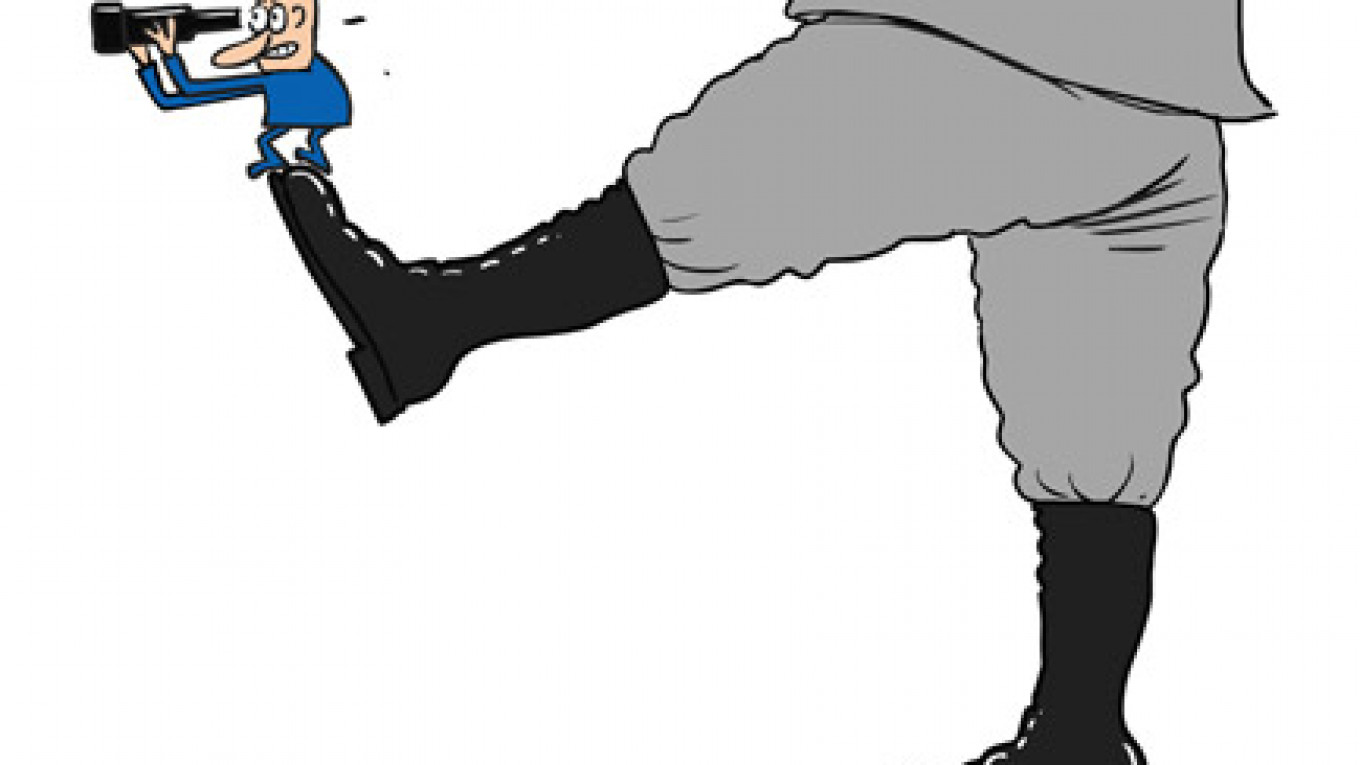

This selective memory and lack of knowledge mean that a considerable portion of Russian society is now happy to line up in columns like so many tin soldiers, glory over the defeat of Nazism and accuse others of fascism even while being more deserving of the moniker themselves.

The public in every country always has a selective memory. The French philosopher Ernest Renan is often quoted for his statement that any nation is a daily plebiscite. But he also pointed out that a nation has the collective ability to forget the past.

However, a nation can only rightfully forget and properly resign to the archive what it has first thoughtfully analyzed, understood and appreciated. After all, some events are too traumatic for national memory and national pride to forget. Otherwise, the day might come when the daily plebiscite to which Renan referred might not assemble for the simple reason that the nation has ceased to exist.

Early April contains at least two dates that patriotic Russians sporting St. George ribbons would prefer to forget: the anniversary of the Katyn and Samashki massacres.

Seventy-five years ago, in April and May of 1940, 4,421 Poles met their end in the obscure Katyn forest near Smolensk.

They died because the Soviet Union took part in World War II, and not only the Great Patriotic War. And however much it might shock today's enlightened Russian boys and girls with their St. George's ribbons, the Soviet Union was not always on the side of good during World War II.

Those 4,421 victims of the Katyn massacre might seem like a trifle compared to the 27 million Soviet citizens who died in the war, not to mention all those killed and trampled underfoot by Stalinism.

But as long as that memory remains — the knowledge of this country's failings as well as its heroic feats — it prevents society from slipping into a totalitarianism that acknowledges only the myth and discards or denies the rest.

Twenty years ago, also in April, Russian troops entered the town of Samashki during the first Chechen war. What happened next was one of the most tragic episodes in the history of modern warfare in the Caucasus: The soldiers killed and burned more than 100 civilians in Samashki.

Of course, it is painful to recall these events just before the Victory Day anniversary celebrations.

But it is also wrong to forget them — that is, if Russia still hopes to find answers to such truly important questions as the following: Is it permissible to kill someone without a trial? Is there a common country for those who pursued a military career after the Samashki massacre and those who buried their parents, brothers and children there in 1995? If so, what are the underlying principles of that country, other than preserving a selective memory of a war that took place 70 years ago?

What happened at Katyn and Samashki does not detract from the greatness of the victory over Nazism, but without preserving a memory of those events and without finding answers to the painful questions they provoke, Russians will not have long to wave their St. George's ribbons.

Katyn, Samashki and other such episodes — including the current war in Ukraine — cannot be swept behind the furniture like shards of a broken vase. At least, that is, if Russia wants to remain a proud victor and not a troublesome punk with criminal inclinations.

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 15 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.