The idea of building a cosmodrome in the Far East first arose in 1996 when the Russian government first became concerned that Russia's space program relied entirely on the Baikonur Cosmodrome in what is now a different country.

And when Russia began the long process of developing the new Angara family of launch vehicles in 1995, it also became clear that the country would need a new launch complex at a geographically suitable location.

The initial solution was to build the military cosmodrome Svobodny on the basis of an existing Strategic Missile Forces facility in the Amur region. However, the necessary upgrades to that complex were delayed for years, first because the Angara rocket program was experiencing serious setbacks, and second because the authorities knew that any additional funds allocated for the military cosmodrome would only disappear through the usual embezzlement schemes.

As a result, government officials abandoned the Svobodny project in 2007 and, at the same location, began construction on the Vostochny launch complex under their direct control.

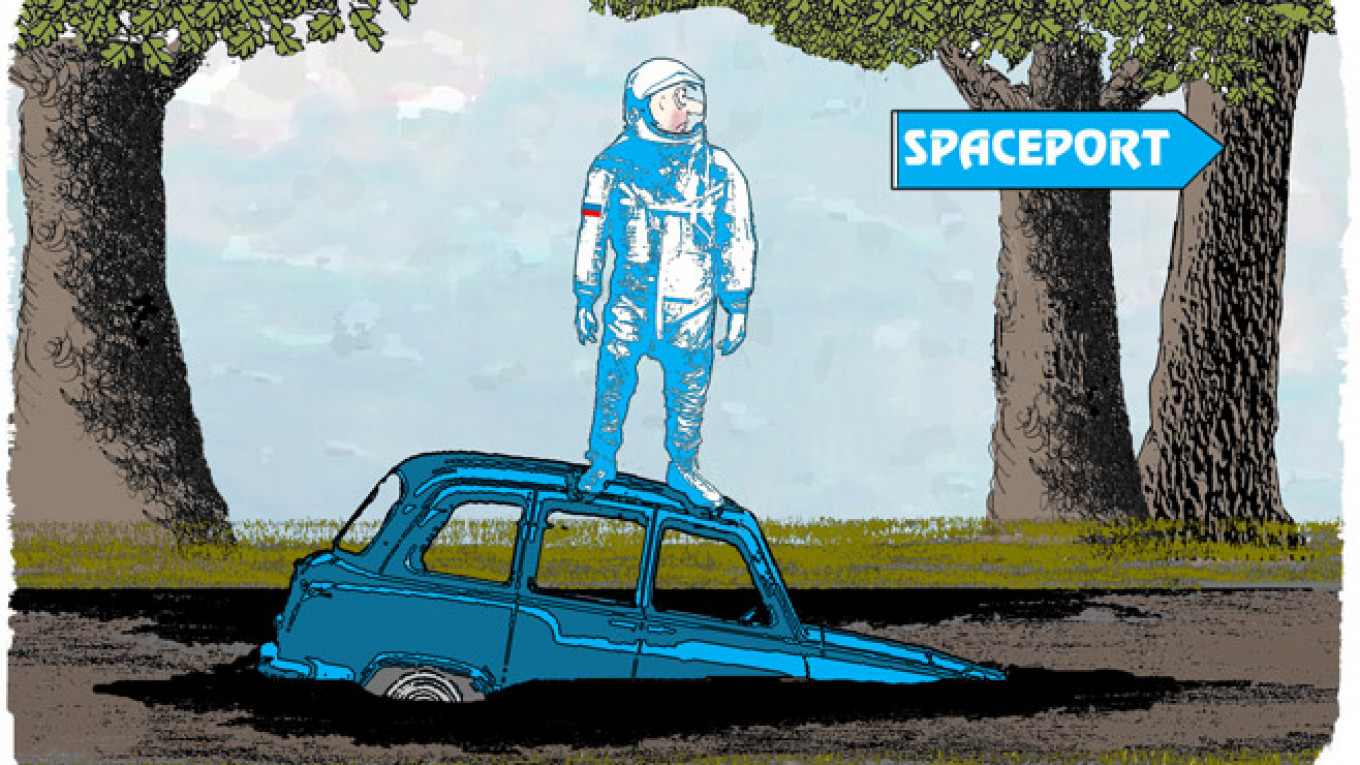

In addition to objective difficulties, the Vostochny Cosmodrome faces problems stemming from the nature of Russia's political system. The objective problems include its remote location and the lack of developed industry in the Amur region, and in the Far East in general.

With no local space industry, specialists must travel in from other regions and key equipment will have to be shipped along the already overburdened Trans-Siberian Railroad. In fact, the first asphalt road linking the region to western Russia was built as recently as 2010.

Meanwhile, the Russian political system is saddling the project with enormous administrative and budgetary costs. The frequent scandals surrounding the project offer clear proof of this. However, those scandals and officials' penchant for boasting that they are "working to achieve Russia's independent access to space"— as it states on the Roscosmos website — mask deeper problems.

However, apart from political goals, the only practical purpose the new cosmodrome fulfills is achieving the timely launch of the new Angara rockets. Space industry officials have stated no other objectives for the project.

Of course, the Angara rockets will enable Russia to stop using outdated Proton rockets, but to what end? "I will think about that tomorrow," Scarlett O'Hara famously said, and apparently Russia's officials are taking the same approach.

For now, the construction of new rockets and a cosmodrome from which to launch them has become an end in itself. This offers an outline of Russia's priorities in space over the next few years.

The Vostochny complex and Angara rocket require something more to justify their existence. That means in addition to moving the launch of state-owned satellites from Baikonur to the new cosmodrome, Russia will try to build a new manned spacecraft that would ride the Angara into orbit.

Such a spaceship has all the signs of becoming a new "national priority": The current Soyuz launch vehicles really are becoming obsolete, and sending cosmonauts into space from Russian territory dovetails nicely with the Kremlin's efforts to extend its new nationalism into space.

What's more, successfully launching cosmonauts into orbit from Vostochny would not only justify the enormous cost of the project, but would also enhance the political image of the ruling regime — thereby imbuing the entire effort with importance. Ironically, all of that will de facto help revive Russia's nearly stagnated space program.

The authorities also consider the Vostochny project as a tool for developing the economy of the Far East. However, they had the same hopes for the extensive construction of buildings and infrastructure for the 2012 APEC summit in Vladivostok — although the outlays involved far exceeded any positive effect for the city.

For that reason, it is unrealistic to expect that the Vostochny Cosmodrome will transform the Primorye region into a U.S.-style "Sun Belt." On the other hand, the project is undertaken in the spirit of colonialism that characterizes Moscow's relations with the regions, and will thus bind the Far East more strongly to the federal center.

On the foreign policy front, the new cosmodrome will inevitably reduce the importance of Baikonur. Russia has no need of two full-fledged cosmodromes, and the last two decades have produced no clear sign that its relations with Kazakhstan will markedly improve.

This is especially true considering the long history of the Russian-Kazakh Baiterek project, according to which Kazakhstan should build a new launch complex at Baikonur where Russia will stage commercial launches of its Angara rockets.

That essentially means that the Kazakhs should foot the bill for modernizing Baikonur so that Russia can occasionally launch its new rockets there in order to maintain bilateral relations, even while Moscow periodically threatens to completely withdraw from using the cosmodrome at all.

Thus, it becomes clear that Moscow wants the Vostochny Cosmodrome for a new stage of colonizing the Far East, as a powerful bargaining chip with Kazakhstan, to bolster the image of the ruling regime and as a launch platform for the supposedly essential Angara rockets.

However, all of this fuss over the construction of Vostochny seems intended to spare officials from having to answer the more basic question of why Russia is sending anyone into space in the first place.

Pavel Luzin is a scholar at the Institute of World Economy and International Relations.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.