In Ukraine, whose tumultuous 20th-century history has spilled over into a bloody battle for its 21st-century identity, every picture tells a story.

Daisy Sindelar traveled to six Ukrainian cities to talk to people about what their old family photographs say to them about who they, and their country, are today. This week, Solomia Lebid, 42, an engineer, instructor in math and computer science, tells her family's story from Lviv.

This article was first published by Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty as part of the My Ukraine project.

I've spent a lot of time collecting family pictures and documents. There seems to be a global tendency to eradicate history, but it's important for me to remember that my family members existed.

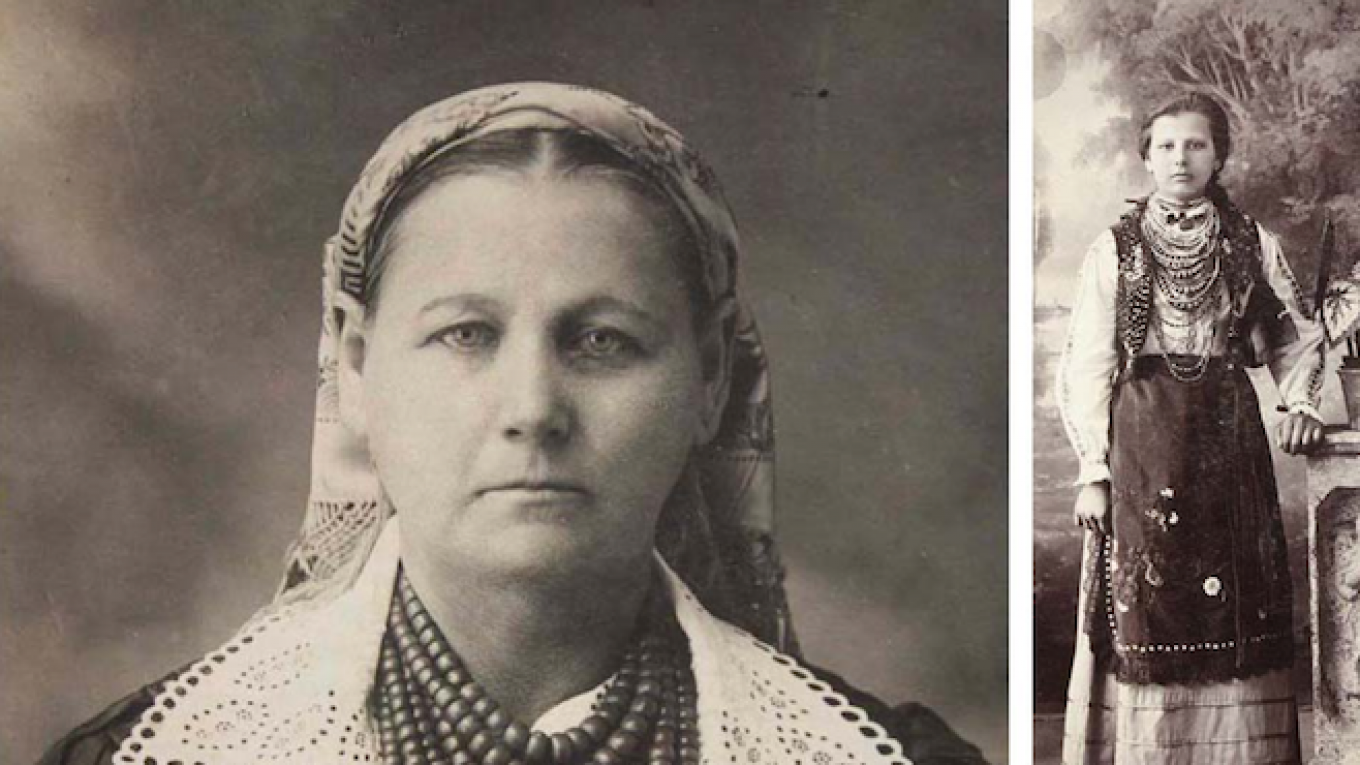

My great-grandmother, Maria, was still alive when I was born, but I never met her. She emigrated to the United States in the late 1930s, to avoid the war.

Maria's daughter, Myroslava, was my grandmother and a very important person in my life.

She grew up mainly in the town of Drohobych and served as a teacher as part of Prosvita, the system founded in the 19th century in Lviv to preserve Ukrainian culture and education.

I still have her school records, so I know that she studied Polish, Latin, Greek, German, math, literature, dance, and nature. When I was growing up and grumbling about science classes, she always told me to stop complaining because as a girl, she had never had the chance to study physics or biology.

Eventually she moved to Lviv. She had hoped to study design in Lyon, but then World War II broke out. She was a very talented seamstress and taught sewing and embroidery classes. For years, she kept the things her students had made for her. They really loved her a lot.

Myroslava Vesela (2d L) and her students showing off their embroidered handiwork.

One time, my grandmother was asked to design outfits for female athletes in Galicia to wear in regional sports competitions.

Up until then, women had been wearing long skirts to play basketball and volleyball, and even for short- and long-distance running. Obviously it was really heavy and uncomfortable, and they asked my grandmother to make something more convenient.

First she designed a skirt with trousers underneath, but even that was too heavy. So eventually she just made trousers for all the women, and then she even made short pants.

This caused a big scandal in the family. Her mother was so disgusted that she stopped speaking to her for two years.

"These are two neighboring kids who came over to play with my grandmother's dog. I love this picture because you can still see little holes from the tracing wheel she used with her sewing patterns. She really liked to take pictures, but I guess sometimes she left them lying around when she was working."

During World War II, she continued to teach. She showed her students how to design clothes and recycle old dresses and shirts into new articles of clothing, so that nothing was wasted.

World War II was really hard on my grandmother, though. She was a prominent member of the local community, and this meant keeping track of everyone who was disappearing or being killed or thrown in jail. Poles, Ukrainians, Jews, professors, priests.

Whenever she could, she tried to get people out of jail. Some of them were so grateful they kept in touch with her for the rest of their lives. But she was haunted by the thought of all the people she hadn't been able to help. Sometimes she woke up screaming.

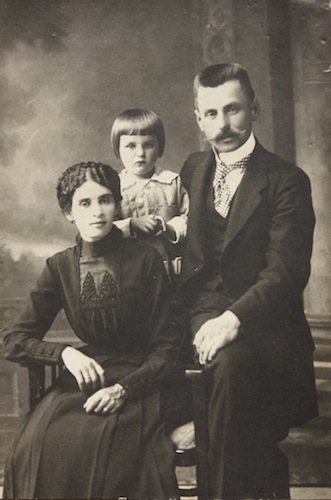

Myroslava and Ivan with Solomia's father, Yuriy, bundled in rabbit fur.

In her personal life, at least, I think she was happy. Her husband, Ivan, was a lawyer. They raised me when I was little, in Lviv. In her papers, I found a note he had written to her: "I love my Myrosia with all of my heart."

"This picture is of my great-grandmother's cousin and her family. They ended up leaving for Poland, I think."

I love my grandparents very much, and anything that belonged to them is very precious to me. Even a cousin of my great-grandmother is important.

People in Lviv have distrust built into their DNA. Too much has happened in our history. So they distance themselves -- they just sit back and watch and wait for the moment when they will finally act. But that mentality is changing. Slowly.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.