In Ukraine, whose tumultuous 20th-century history has spilled over into a bloody battle for its 21st-century identity, every picture tells a story.

Daisy Sindelar traveled to six Ukrainian cities to talk to people about what their old family photographs say to them about who they, and their country, are today. This week, Mykola Chaban, 56, a journalist and ethnographer, tells his family's story from Dnipropetrovsk.

This article was first published by Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty as part of the My Ukraine project.

Everyone in Ukraine has an interesting history. I've researched so many families — my own and other people's — and it's always fascinating.

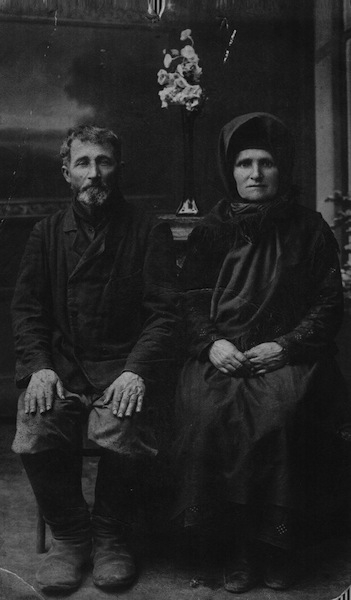

My great-grandparents, Martyn Harzha and Vustya Horpyna, are a case in point. Vustya was pure Ukrainian, but my great-grandfather was a Vlakh of Romanian origin. They were peasants, and they had two horses. This made them relatively prosperous for the time.

These horses caught the eye of the Makhnovshchina, the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine. They kind of promoted themselves as Ukrainian Robin Hoods. Stealing from the rich, giving to the poor, that kind of thing. Very fair-minded. So when it came to my great-grandfather's horses, they didn't steal both — only one.

My great-grandfather was very angry, and he marched off to talk to the group's commander, Batko Makhno. Everybody feared the worst. Martyn made the case that he wasn't actually all that rich, and that he really needed the horse back.

The horse was returned. Occasionally Batko Makhno liked to make those kinds of magnanimous gestures.

Martyn Harzha and Vustya Horpyna, early 1900s.

Martyn died of Spanish flu in 1919; Vustya died of starvation during the Holodomor, Stalin's forced famine. She went to a hospital for help, but they just said, "You don't need medical help. You need food." They left her lying on a sheet on the floor to die.

Their daughter — my grandmother, Yevdokia — survived the famine, but her life was very hard. She and her husband Andriy worked on a kolkhoz, a collective farm, in their village of Mayorka. But then Andriy was arrested for reciting a rhyme about Stalin. "Spasibo Stalinu-Gruzinu, za to chto obul nas v parusinu i rezinu." Thank you, Stalin the Georgian, for giving us shoes made of burlap and rubber.

It was just a little joke about shortages, but it didn't go over very well. My grandfather was sentenced under Article 58, the article on anti-Soviet propaganda.

Andriy was sent to the Solikamsky labor camp in the Urals. He died later the same year. They said he died of a heart condition, but that was their politically correct way of putting it. We found out later he died of pellagra, which is caused by malnutrition. A lot of people in the camps died of that.

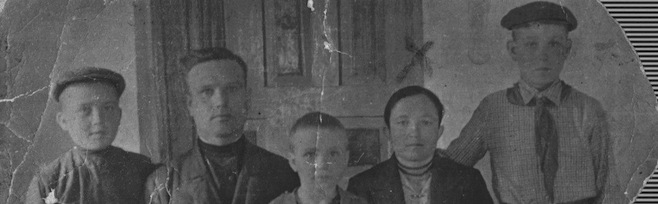

(L-R) Petro, Andriy, Lidia, Yevdokia, and Mykola Chaban.

I was named after my Uncle Mykola. He became the man of the house when he was 14.

My grandmother and her three children made it through the German occupation, but during the Lower Dnepr Offensive in autumn 1943, when Soviet troops were pushing the Nazis back west, Mykola was forced into military service. He was killed almost immediately. He was 17.

He hadn't been given any kind of training; he didn't know how to defend himself. Stalin wanted to liberate Kiev on the anniversary of the October Revolution, and he was pushing the Soviet Army as hard as he could. That caused a lot of unnecessary bloodshed.

Mykola Chaban (left) and his boyhood friend Vanya Zaskoka.

My uncle was killed about 20 kilometers away from Mayorka. When my grandmother heard the news, she walked to the spot to find him. His body had been thrown in a mass grave. But she was able to identify him.

She had given him a scarf, a spoon, and some meat pies before he left. He still had them with him — that's how quickly he was killed.

The military officer there said she was free to take the body away, but she had no way to carry it. She walked back to her village to see if she could borrow a horse from the kolkhoz.

They refused, because they were afraid the Soviet military would just make off with a horse. But they allowed her to take a cow. So she walked back to the mass grave with the cow, and then slowly pulled Mykola's body home so she could bury him in Mayorka.

Lidia, Yevdokia, and Petro Chaban, Baku, 1948.

So within a decade, my grandmother lost her mother, her husband, and her oldest son.

After World War II ended, there was a second wave of famine in Ukraine, so my grandmother took her two remaining children — Lidia and my father, Petro — and moved to Azerbaijan.

They packed three small suitcases; one of the suitcases was stolen on the train. But they made it to Azerbaijan, where they could at least earn enough to buy food.

My father started his army service after this, and served in Armenia. He was not impressed by military life in any way. He still hates when veterans put on all their medals and walk around. To him, the real soldiers were the ones who were killed or injured.

After Stalin died in 1953, they felt like it was safe to move back to Ukraine. But their farming life was already over. They settled in Dnipropetrovsk. My father found work in construction.

While my grandmother was still alive, we went to visit Mykola's grave on a regular basis. She died in 1994, when she was 87. She's buried next to him now.

People here are very tough. We've been through a lot. It's very common for older women to say, "I can endure anything, as long as there's not a war." So it's very painful to see what's going on now in Ukraine. We know what war is, and it's horrible.

"During World War II, the Russians really hated us for living under occupation. And now they're using it against us again, calling us Nazis and fascists."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.