The authorities began speaking about the threat of a so-called "color revolution" even more frequently this past year despite the fact that, until the recent imposition of sanctions, Russians were better off than ever before in their history — and they knew it.

Such a phenomenon seems strange to an outside observer: Why would citizens organize a revolution just as they have gained their first opportunity to buy a second family car and a larger apartment, or to take a long hoped-for trip abroad? Isn't economic prosperity the best antidote to revolution?

Just the same, government propaganda effectively employs the technique of raising the specter of revolution in order to immobilize an already nearly immobile population. The authorities have only to utter the word "revolution" and nearly all 143 million Russians freeze in their tracks as if bewitched. What accounts for this strange phenomenon?

The fear of revolution is probably one of the Russian people's worst fears, along with the threat of the country breaking apart even further or China occupying the Far East and Siberia. That fear compares in intensity with what the residents of some remote Russian village would feel if their town were suddenly overrun with immigrants from Central Asia or what most Russians would feel if someone like Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov were to suddenly seize power in the Kremlin.

These are strong emotions rooted in cultural factors that have nothing to do with political or economic forecasts. The fear of revolution often reaches mystical, almost apocalyptic proportions. And truly, for many ordinary Russians, a revolution would literally signal the end of the world, replete with seven angels blowing trumpets as prophesied by St. John the Evangelist.

And that fear is spreading, as seen by the rise of an entire political movement — Russian nationalism. Even before events in Ukraine, the rhetoric of the nationalists — always very emotional and full of excesses — warned of impending disaster: revolution, occupation by foreign powers and the colonization of Russian territory by foreign powers.

In addition, the Russian Orthodox Church and associated groups print literature containing collections of dire prophecies about the last days of Russia that has proven very popular in the provinces. These tracts claim that revolution and coup d'etat are signs of the second coming.

Most Russians would react very negatively to a revolution of any stripe — communist, liberal, nationalist or under the black banner of Orthodox fundamentalism.

That mind-set did not form in a vacuum, but as the result of several large-scale media campaigns the authorities have conducted over the last 25 years.

The first such campaign launched in 1991 with the publication of thousands of documents denouncing the Bolsheviks and Vladimir Lenin for colluding with German intelligence, for acts of unjustifiable cruelty and for pursuing utopian plans for restructuring Russian society in according to Marxist dogmas.

The documents blamed the revolutionaries for all of the many ills that Russia subsequently suffered during the 20th century — from the failure to defeat Germany in World War I to the severe economic crisis that the Soviet Union suffered on the eve of its collapse.

According to this logic, were it not for the revolutionaries, Russia would now be a developed and prosperous country and its citizens would be just as well fed and well groomed as those in the United States and Europe. If not for the revolutionaries and those who sympathized with them, they argue, Russia would not be in this condition.

These ideas actively fueled anti-revolutionary emigre literature that became available to every Russian citizen after the fall of communist ideology. According to various sources, as many as 2 million people fled Russia during the civil war.

Most of them were educated, creative and prosperous people. There was even a "ship of philosophers" — approximately 200 writers, philosophers and social commentators that the government deemed undesirable and literally shipped out of the country on a single vessel.

Not surprisingly, for the 70 years that the Iron Curtain separated them from their homeland, they wrote and utilized all their skills and talents to propound the evils of revolution in general, and the Russian Revolution in particular.

Nobel Prize winner Ivan Bunin, who had emigrated to France, wrote numerous anti-revolutionary works, including the novel "The Cursed Days" that Russian filmmaker Nikita Mikhalkov turned into a major production for the screen last year. Both the novel and the film adaptation are full of sharply worded criticisms of the revolutionaries that capture the essence of Bunin's works for Russian readers and viewers.

The role of the Moscow Patriarchate deserves special mention here. The Russian Orthodox Church opposes revolution on the grounds that thousands of people were martyred by the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, at the Butovo firing range outside Moscow. Every Orthodox church in Russia displays an icon honoring those who gave their lives for their faith.

According to the Church, the greatest of those Christian martyrs was Tsar Nicholas II, who was killed together with his family and recently canonized. Every day, in sermons delivered in churches across Russia, the people are told that revolutionaries killed the emperor's children and that revolutionaries are somehow less than human.

The modern successors of the Communist Party conducted the next most important anti-revolutionary campaign. Not finding a place for themselves in post-Soviet Russia, they blamed all of societies' many ills — economic collapse and the resulting sharp rise in crime, the collapse of the "red empire" and local conflicts in the former Soviet republics — on the coup of 1991, a revolution they claim was orchestrated by capitalist enemies of the Soviet people.

While the ruling regime utilized powerful state-controlled media to conduct its anti-revolutionary campaign, the now marginalized communists spread the same message through word of mouth and longstanding informal social networks.

As a result, the Russian people were subjected to at least two similar outpourings of negative emotion, with rulers, communists and the Orthodox Church all blaming their many ills on revolution.

During the past decade, the authorities built upon this foundation to create several more negative images, this time connected specifically with color revolutions. They waged a powerful campaign to discredit the Orange Revolution in Ukraine in 2004, claiming that U.S. intelligence had assisted those who overthrew former Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma and paid masses of Ukrainians to protest on the streets and squares.

The same was true regarding Georgia, where Moscow consistently labeled revolutionaries enemy agents working against their own country. With the outbreak of mass street protests in Moscow in the winter of 2011, the Kremlin propaganda machine went into overdrive, painting the tens of thousands seeking change as capital dwellers depraved by easy money, as gays and Jews causing unrest in a vicious desire to promote their own lifestyles and values.

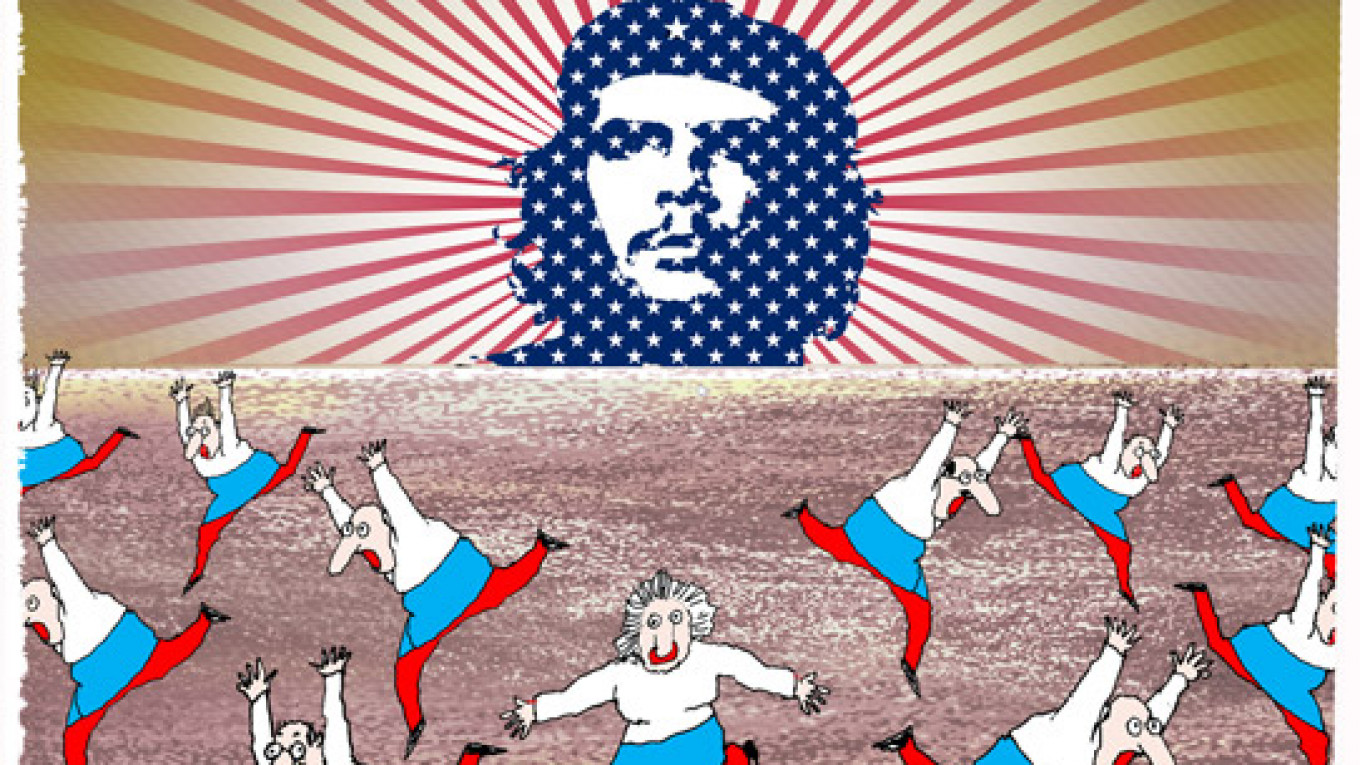

As a result, the very word "revolution" now carries a strictly negative connotation in Russia. Even Argentine former revolutionary Che Guevara is often referred to as a dirty warlord akin to a Chechen separatist — yet another bogeyman that Russians have been conditioned to fear like the plague.

Maxim Goryunov is a Moscow-based philosopher.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.