When a film version of Modest Mussorgsky's opera "Khovanshchina" appeared in 1959 and posters advertising it were displayed throughout Moscow, a little girl was overheard asking her mother, "What does 'Khovanshchina' mean?" "Can't you can see for yourself, stupid?" the mother replied. "It's the name of a movie."

Nearly every Russian must surely know the opera's title, but I would reckon that most have little or no idea what it's about. And even among those who are aware that it concerns the upheavals of the 1680s that led to Peter the Great taking command of the Russian throne, I would also reckon that a large majority probably believe it to be a long and tedious work they wouldn't be caught dead sitting through.

I have to admit, prior to the new production of "Khovanshchina" last month at the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Musical Theater, I found the opera pretty heavy going in the versions I had previously encountered, including those that appeared briefly at the Bolshoi Theater beginning in 1995 and 2002.

But rather miraculously, the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko has managed to turn "Khovanshchina" into a thoroughly compelling experience, thanks to a carefully constructed and highly original staging by the theater's artistic director of opera, Alexander Titel, musical direction by one of Russia's most justly esteemed conductors, Alexander Lazarev, and singing by a chorus and soloists of remarkably high quality.

Mussorgsky created his own libretto for "Khovanshchina" and set it in 1682, the year the sons of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, nine-year-old Peter (later, "the Great") and his severely handicapped half brother Ivan, 10 years his senior, were chosen as joint rulers of Russia. Presiding over them as regent was Sofia, Peter's half sister and Ivan's sister, a strong-minded woman with an eye set on ruling Russia all by herself.

In fact, Mussorgsky joined together the events of 1682 and those that followed six years later to create an epic historical drama revolving around the forces that favored a Russia leaning toward Western Europe (the supporters of Peter) and those who wished the country to follow its traditional ways (the supporters, more or less, of Sophia).

As in the case of his direction in recent seasons of Sergei Prokofiev's "War and Peace" at the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko and Mussorgsky's "Boris Godunov" in Yekaterinburg, Titel has again, with "Khovanshchina," proved himself a master at unraveling and clearly setting out the often confusing story of a great Russian historical opera and injecting real drama into even its most static moments.

Mussorgsky labored over the music of "Khovanshchina" for most of the decade preceding his death in 1881, but in the end left only a piano score, with the opera's final act left unfinished, and only two scenes orchestrated. Taking upon himself the task of completing the opera, the composer's close friend and colleague Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov discarded some of Mussorgsky's score and orchestrated the rest. Eventually, other attempts were made to provide an orchestration, notably one concocted by Dmitry Shostakovich for the 1959 film version.

In recent times, most productions of "Khovanshchina" have employed the Shostakovich orchestration. For my own part, I had hoped the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko might choose, as the Bolshoi did in 2002, to return to Rimsky-Korsakov's version, which, for all of its overly bright orchestral colors, seems to more comfortably fit the music than the often brash-sounding creation of Shostakovich.

The theater, however, opted for Shostakovich. And hearing that score under the masterful baton of Lazarev, who served with great distinction as chief conductor and musical director of the Bolshoi from 1987 until his departure in 1995, I found my reservations gradually disappearing. Somehow, Lazarev made it all sound perfectly natural and appropriate.

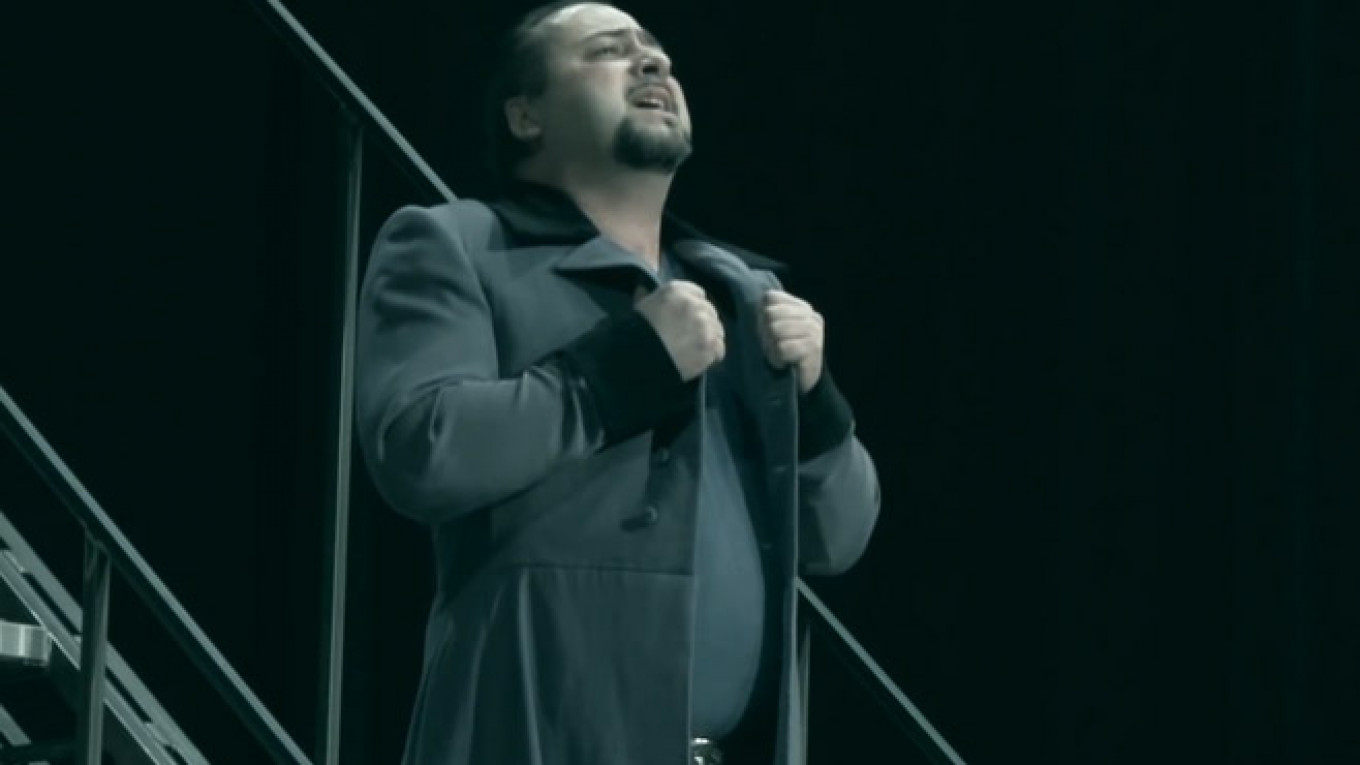

Among the cast on opening night, there were particularly outstanding contributions by bass Dmitry Ulyanov as Ivan Khovansky and tenor Nazhmiddin Mavlyanov as Vasily Golitsyn, as well as something of a revelation in the Marfa of mezzo-soprano Ksenia Dudnikova. Mezzo-sopranos of her caliber, with full-bodied lower registers and clean, vibrato-free notes in the upper vocal reaches, have rarely been heard in Moscow over the past two decades. And though I missed her Amneris in the theater's "Aida" last season, I'm not at all surprised it has put her in the running for a Golden Mask award next month.

But perhaps the principal heroes and heroines on stage were the members of the theater's chorus. I have heard them sing quite beautifully in the past, but never with such fervor as they displayed in representing the people of Russia caught up in, and at the mercy of, the country's all-too-familiar intrigues of church and state.

"Khovanshchina" next plays on April 18 and 19 at 7 p.m. at the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Musical Theater, located at 17 Bolshaya Dmitrovka. Metro Chekhovskaya. Tel. (495) 723-7325. www.stanmus.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.