KIEV — The rhetoric is as melodramatic as ever, but this time around Russia's threat to cut off Ukraine's natural gas is mostly hot air.

After months in which Kiev has been faithfully paying for gas and Moscow reliably supplying it under a deal brokered by the European Union, last week saw the quarrel erupt anew.

Russia, which has cut off the gas three times in the past decade, including for six months last year, has once again threatened to switch off supplies unless Ukraine sends more money within days.

Ukraine on Friday sent a small prepayment of $15 million to Russia for March natural gas deliveries, but the sum is enough to cover only up to two days' supply.

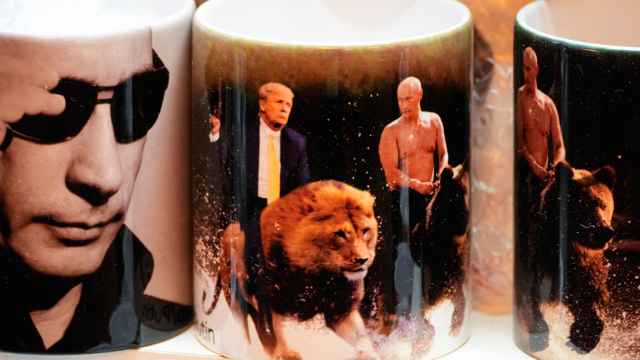

After a public announcement by Russian gas giant Gazprom's boss Alexei Miller that Kiev had put European supplies in jeopardy, Vladimir Putin personally jumped in on Wednesday.

The Russian president said Ukraine's lack of "financial discipline" could cause energy shortages across the continent — a reference to the fact that Russia supplies about 30 percent of the EU's gas needs, half of that via Ukraine. He accused Kiev of threatening to cut off gas to separatist regions in the east of the country, an act which he said "smells of genocide."

Kiev has responded by accusing Russia of failing to meet its contractual obligations under the EU-brokered deal.

But for all the noise from both sides, the natural gas feud that has divided the two neighbors since long before Russian-backed separatists went to war against Ukraine last year is no longer the make-or-break crisis it once was.

The EU shrugged off Miller's and Putin's threats that cutting off Kiev could cause supply problems for European customers further downstream. Nothing of the sort happened during the six-month shutdown last year.

Not What It Sounds Like

The timing of the latest quarrel is no coincidence. The winter season of high demand is ending, and the temporary, EU-mediated winter supply deal is due to expire at the end of next month. Both sides are gearing up to negotiate terms to replace it.

"What's been happening the past few days, these statements by Miller and Putin, is all just a prelude for talks between Russia and Ukraine over a summer deal," said Valentin Zemlyansky, a gas industry analyst in Kiev and former spokesman for Ukraine's gas firm Naftogaz.

The threat to "cut off" Kiev's gas is no longer quite what it sounds like. In the past, Kiev bought its gas from Russia on credit. That meant that Ukraine could find itself asking for more gas, only for Russia to refuse to supply it.

Nowadays, Kiev pays for any Russian gas it receives with cash up front. If Russia does halt gas to Ukraine in coming days as Putin threatened, it won't be because Moscow has decided to cut Kiev off; it will be because Kiev hasn't ordered any.

In public, Ukraine says it is not buying more Russian gas because Moscow violated delivery terms and may have sent some gas that Kiev had paid for to separatist areas without its permission.

The issue which smelled to Putin like "genocide" is political dynamite for both sides. But in practice, the volumes for rebel areas are small and Kiev couldn't cut them off if it tried, because rebels and Russians control pipes at the border.

Brussels has summoned Russian and Ukrainian officials for talks on Monday, including over payment for rebel regions. Moscow raised the possibility on Thursday of supplying the rebel areas for free.

Reverse Flow

In private, Ukrainian gas industry sources say there is a far simpler reason why they have not ordered more Russian gas: They don't need it. At least not yet.

A new source of supply since last year — so-called "reverse flow" in which gas is sent back east to Ukraine from Europe through pipes originally built to take it west — means Kiev is less dependent on Moscow than in years past.

"All these threats by Gazprom are not particularly frightening for us, as the situation has radically changed compared to last autumn," said Zemlyansky. "We've passed through the winter season — the mild weather really helped us, as well as decreased consumption by industry."

He estimated Ukraine would consume about 35 billion cubic meters of gas in 2015. That is not far out of line with what it produces itself and imports from Europe, although it will be important to build up reserves for next winter's peak.

Ukraine did need gas from Russia to get through the past winter, but the actual amount of gas it says it ended up buying under the EU-brokered deal was comparatively small.

Ukraine's Naftogaz says it spent $830 million buying 2.39 billion cubic meters of Russian gas in total over the three winter months of peak demand. That works out to about 26 million cubic meters per day, less than it produces itself and less than it receives in reverse flow from Europe.

Ukraine may still need to buy gas this year to replenish its reserve tanks before next winter, but with global energy prices falling and warm weather coming, there is little rush. Ukrainian gas officials believe there is still capacity to increase the reverse flow from Europe.

For now, Kiev does not want to trumpet its newfound safety from Russian threats to its supply, in part because Moscow's growling helps motivate Europe to focus on the reverse flows, said one Ukrainian gas industry source.

"We would be able to survive without Russian gas for some time. But we do not want to say that everything is fine. We want Europe to consider increasing reverse flows to Ukraine, it will be a logical step."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.