In Ukraine, whose tumultuous 20th-century history has spilled over into a bloody battle for its 21st-century identity, every picture tells a story.

Daisy Sindelar traveled to six Ukrainian cities to talk to people about what their old family photographs say to them about who they, and their country, are today. This week, Areta Kovalsky, 30, an advertising manager and blogger, tells her family's story from Lviv.

This article was first published by Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty as part of the My Ukraine project

I'm Ukrainian-American, but I moved to Ukraine a few years ago. Lviv used to be my ancestral home. Now it's my permanent home.

I'm pretty passionate about researching my family history. It's great to be here in Lviv where I can find old records and grave sites and in some cases even distant relatives.

My family is lucky in that we've held on to a lot of our photographs. One of my favorites is one of the oldest, from the early 1900s. It shows my great-great grandparents with some of their children and nieces and nephews.

I think it's a very interesting picture because it shows a good portrait of life in Galicia, the territory that comprises parts of modern-day western Ukraine and southeastern Poland, where people of different ethnicities and religions lived together pretty harmoniously.

My great-great-grandfather, Leon Bednawski, was Polish and Roman Catholic. My great-great-grandmother, Yosifa Kuhn, was Ukrainian and Greek Catholic.

At that time it was common for Poles and Ukrainians to intermarry, but they tried to preserve both cultures at home. It was traditional for the sons to be brought up in the religion and language of the father, and the daughters brought up in the mother's.

Several of Leon and Yosifa's children died young, and in one instance a son and a daughter shared a grave site. The son's plaque is in Polish, the daughter's in Ukrainian. It's a custom that had really interesting consequences in this part of the world, where borders and nationalities kept changing.

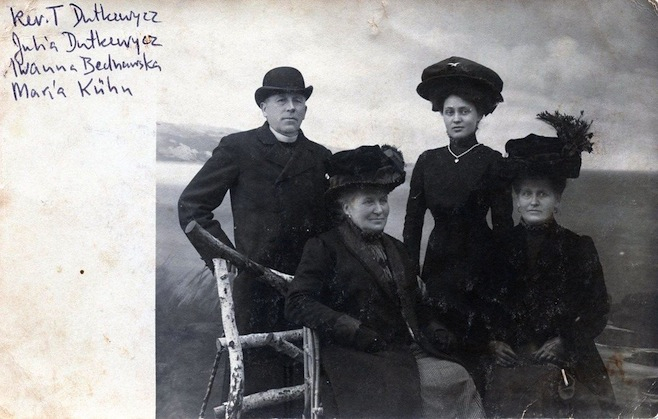

Ivanna Bednawska (top right) with two aunts and her uncle, Toma Dutkevych, Italy, 1908.

I love this picture because of the hats. But it's also interesting because it shows the kinds of perks that relatively well-off Galicians enjoyed at the turn of the century.

My great-grandmother, Ivanna, had lost several of her siblings to either tuberculosis or typhus, and her parents sent her abroad to keep her from getting ill.

She traveled with two of her aunts and an uncle. The uncle, Toma Dutkevych, was a parish priest in Chishky, near Brody. But he was also pretty prosperous because he was a very successful farmer.

He and his brother helped create the Silskiy Hospodar movement, which promoted modern farming techniques. It was part of the same cooperative movement in Galicia as Prosvita and Narodna Torhovla, which helped improved education and trade.

Toma had a big library and was friends with Ivan Franko, the poet and activist, who would come to borrow his books.

Bohdana, 19 (left), and Maria, 12, in 1931.

Ivanna had two daughters: my grandmother, Bohdana, and her sister, Maria. They were born near Przemysl, which is now in Poland, and grew up in Brody. They were separated during World War II. They didn't see each other again for almost 50 years.

My grandmother had already been arrested once for her ties to the Ukrainian nationalist movement, which was active in Galicia. When the Soviets resumed power after the war, she knew she had to get out of there before she was arrested again.

Bohdana fled with her husband, their baby, her mother, and her grandmother, who was already in her '90s. (Amazingly, her grandmother — my great-great-grandmother, Yosifa — survived the journey. She died in Michigan in 1951.)

They couldn't find Maria before they left. She was in Brody, which had come under heavy bombardment. She had joined the UPA, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, the partisan army fighting for an independent Ukrainian state. In 1946, she was arrested.

Maria being held above the water, Brody, 1936.

Maria spent 10 years in prison in Mordovia, and another five years in exile in Krasnoyarsk.

Eventually she came back to western Ukraine. She even wrote a book about her life as a partisan. But it was years before she knew what had happened to Bohdana and the rest of the family. They didn't see each other again until 1990.

I spent time at Euromaidan, and Lviv has had its own unrest over the past year. At this moment in Ukraine's history, I can't help but think about my ancestors and how they must have felt during World War II and the partisan struggles to liberate Ukraine.

I feel very close to them, being here.

Areta Kovalsky, 30, advertising manager, blogger.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.