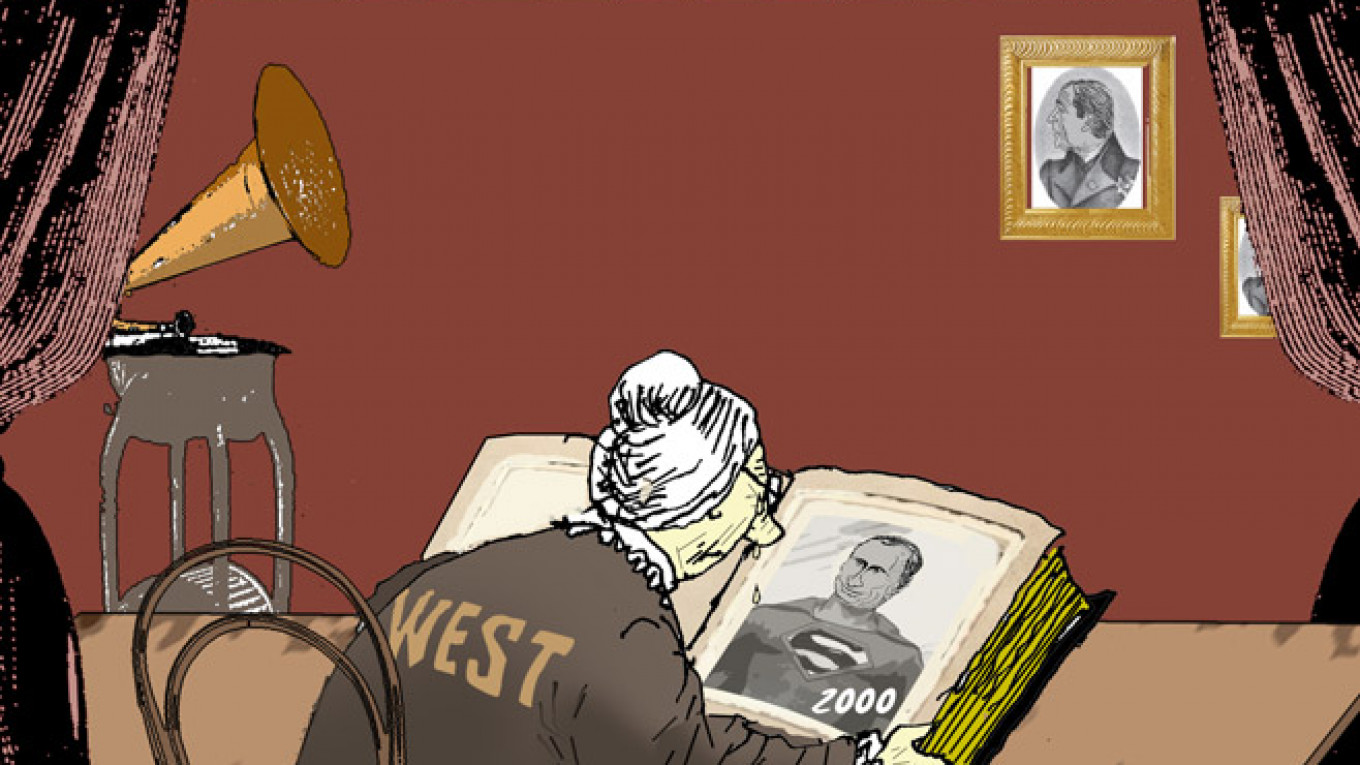

Many Western leaders and officials want to see change in the Kremlin. Not just a change in policy, but a change in the occupant. However, this is balanced by a concern as to who — if anyone — could succeed the current president, whether they would be any better, or indeed could actually control this sprawling country and a willful elite. The answer is simple: they need to bring back Vladimir Putin.

The 2000 vintage Putin, that is.

After all, while the West would theoretically love to see a liberal, reforming democrat at Russia's helm, in practice its real goal, for now, is someone rather different. He has to be tough enough to keep Russia together and under control, pragmatic enough not to let the nationalist rhetoric necessary to placate the right shape policy, far-sighted enough to want to work with the West. He also has to be enough of an insider to understand the elite and vice versa, but not so much as to be mired in factional politics and corrupt deals.

This is just what the West had in the early Putin. He knew how to play the patriot card, and his ruthless suppression of the Chechens was not just a gambit to establish his political credentials, it also reflected his visceral sense that Russia had to be held together, by whatever means necessary. At the same time, though, he saw Russia's future as being best served by a certain partnership with the West and could ignore or redirect the nationalist hubbub when it suited.

He addressed what was then the West's primary security concern: not "little green men" on Russia's borders, but anarchy within the borders. The oligarchs — in the main, exploitative kleptocrats, not enlightened entrepreneurs — were tamed, kingmakers no more.

Organized crime was brought under control (in every sense of the word) and its indiscriminate bloodletting on the street ended. Talk of Russian nuclear weapons turning up in terrorist hands, or of the violent fragmentation of the federation, all became a thing of the past.

This is not to sugarcoat the old Putin. From the first he was an authoritarian and he hounded his enemies on charges false and exaggerated, while shielding his friends regardless of their misdeeds.

But especially in his first term, he also permitted a degree of media freedom and plurality, would occasionally engage with civil society, and spent money on health and education. Besides, he wasn't the ailing, erratic, intoxicated, venial and increasingly incapable Boris Yeltsin.

He may not have been the West's ideal Russian leader, but he was one with whom, to paraphrase former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's summation of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, we "could do business together."

And business we did. Intelligence sharing about jihadists after 9/11. Western investment. There were all kinds of specific points of friction and irritation, from the anti-ballistic missile shield spat to his dismay at the 2003 Iraq War, but in essence these were manageable.

The hope of the West is presumably to turn back the clock, to make 2015 vintage Putin return to his 2000s persona. Is there any likelihood of this happening?

Probably not. It is not just that the context has changed, Putin does appear increasingly genuinely to regard the West as an active threat. He may not really believe that NATO tanks would ever roll eastward — and he would be foolish if he did — but he certainly does regard Western ideas and ideals as being corrosive to Russia's distinctive culture and identity.

Besides, there is also a point behind the often ludicrous claims of Western — American — campaigns to foment "color revolutions" across Eurasia, not least in Russia. I find it hard to believe that Washington has an active program for regime change in Russia. Apart from the U.S. administration's essentially risk-averse stance, the thought that it could come up with, plan and execute any kind of Machiavellian scheme without leaking or botching it seems to give it far, far too much credit.

However, every dollar spent supporting pluralism against the engines of Kremlin political technology, on nurturing investigative journalists willing to highlight official corruption, on lauding maverick politicians and activists challenging the government is actually being spent on gradual and indirect regime change. They seek to change if not the actual government, then the way and system it governs. There is little point trying to pretend otherwise, whether to the Kremlin or to ourselves.

In that context, the West is hoping that even if it cannot change Putin's mind, a combination of sanctions, condemnation, economic hardship and grassroots disquiet will at least force him to act as though it has. It may happen, or it may — and this is probably the more likely outcome — in due course galvanize insiders to decide Putin is becoming a liability rather than an asset.

However, any new regime would have to balance the interests of the elite and control of the masses with building a new relationship. It might be that, rather than a starry-eyed democrat, it requires a tough pragmatist. You know, someone like that prime minister turned president inaugurated in 2000, one Vladimir Putin.

Mark Galeotti is professor of global affairs at New York University.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.