The Institute for Research and Development in Eastern Europe, in Warsaw, recently invited me to Poland for a couple of days. The first thing I saw at the Warsaw airport as I arrived last Sunday was a U.S. Air Force transport aircraft. The border guard slowly and carefully inspected my passport, studying every entry and exit stamp showing visits to various Schengen countries. The strict border guard, the U.S. military aircraft and the news from eastern Ukraine playing on the television screens in the airport, hotel and cafe made it clear that a very serious conflict is taking place.

And yet Sheremetyevo Airport in Moscow is full of people. And Russians boarding regular flights to London, Washington and Munich do not look very much like refugees desperately escaping the zombie apocalypse. Perhaps there are fewer travelers than there were six months ago, and they probably have less spending money than they did before, but life goes on.

I was attending a forum called "Ukraine and Europe: A New Beginning," and frankly, it was no easy task to represent Russia there. And it was equally difficult for Ukrainians and Europeans to listen to a Russian with an open mind. And although Russian was not originally one of the working languages of the event, it quickly joined the ranks of English, Polish and Ukrainian.

This was not an attempt on the part of the few Russian guests to demonstrate imperial arrogance or to disguise their spotty command of English. It simply turned out that at this Polish-Ukrainian forum, Russian remains the lingua franca for a large number of people. One can only hope that we will be able to speak it outside the framework of war.

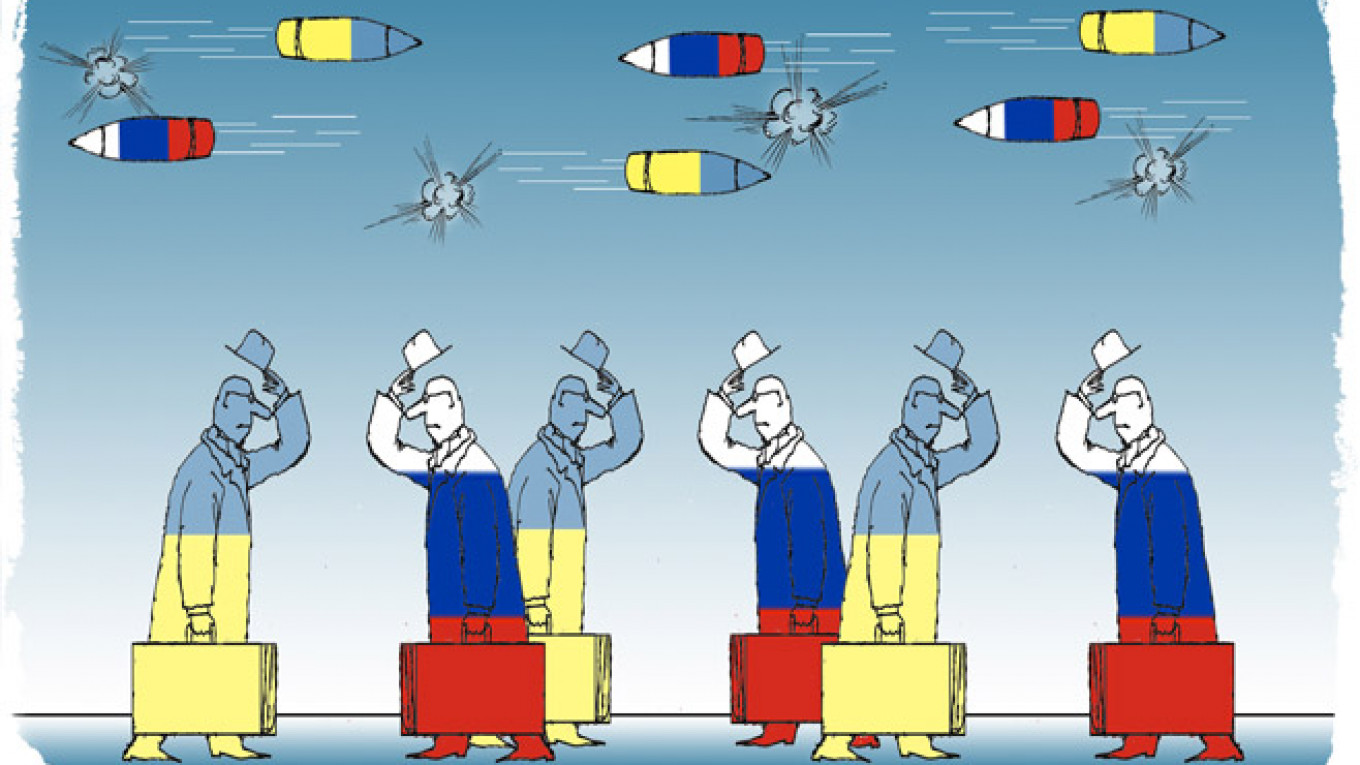

Interestingly, the parties in this conflict are not separated by an impenetrable front line. Only a relatively small number of people have difficulties crossing the Russian-Ukrainian border. And while full-scale hostilities continue at one part of that border, people and goods move freely through a different segment of it.

And that exchange of goods is accompanied by lobbying efforts as if there were no war at all. Russian firms working in Ukraine do not advertise that fact at home and try to respect the Ukrainian rule not to sell their products in Crimea. Ukrainian companies also work in Russia. Moscow and Kiev unleash extremely harsh rhetoric at one another, even while the two countries continue working together very harmoniously in other ways.

All of this gives a sense of unreality to everything that is happening. There is a term that describes the conflict in Ukraine: irredentism.

Prior to this instance, it would have been difficult to imagine that a country might support the irredentists on its neighbor's territory while at the same time selling that neighbor gas and buying, for example, fieldstone from it in return.

It would have been equally difficult to imagine that a country that annexed part of its neighbor's territory — or, as officials like to say in Moscow, "extended its jurisdiction" — also voted in the UN Security Council for a resolution supporting that same neighbor's territorial integrity.

Irredentist conflicts are, by definition, local problems. There is a huge distance between such localized irredentist conflicts and a Cold War-like global confrontation. And yet the current situation has many signs that it could escalate very seriously, and the presence of a U.S. Air Force plane at the Warsaw airport is only the beginning. The fact that leaders negotiated for many hours last week in Minsk itself testifies to how much is at stake if they ever stop talking.

For those living in the war zone, there was little to show for those talks. The official signatures of four national leaders were supposed to have put a stop to the fighting as of midnight on Sunday, Feb. 15.

As recently as one year ago, everybody assumed that it was impossible for full-scale hostilities to erupt in Europe. That genie of open hostilities escaped briefly from its lamp back in Georgia in August 2008, but was forced back in again after just five days. This time, the conflict has been raging for months, thousands have died and whole regions — including homes, factories, roads and social infrastructure — have been reduced to ruins reminiscent of Bosnia and Rwanda. Public order has been destroyed.

Apparently, values and institutions have become rather inflated since August 2008, such that now the agreement for a cease-fire is more important than the cease-fire itself. Perhaps the daily deaths of several people somewhere near Debaltseve is a fair price to pay for saving the far greater number of lives that would be lost from a military escalation. Or perhaps it is coming to resemble the dystopian Orwellian adage that "War is peace."

It came off as something of an aberration for Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov to speak of the collapse of world order during a recent security conference in Munich, where he was much ridiculed. Very negative changes have been occurring within Russia itself, and this has created a prism through which it appears that the whole world is about to collapse.

In fact, that vague presentiment that something terrible is about to happen on the domestic front makes Russian leaders peer through their window on the world with a similar sense of impending doom.

But the view from Debaltseve is even worse: From that vantage point, it seems that something really is not working in the world if the major powers cannot stop the killing.

And although the conflict in Ukraine is not the first, and probably will not be the last war on the territory of the former Soviet Union, the fact that it has lasted this long is forming a dangerous precedent for a number of regions that are also torn by ethnic and territorial disputes.

It is time to come up with a fitting finale for this horror film before — against the will of the producer and the audience alike — it spawns sequel after bloody sequel.

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 15 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.