In Ukraine, whose tumultuous 20th-century history has spilled over into a bloody battle for its 21st-century identity, every picture tells a story.

Daisy Sindelar traveled to six Ukrainian cities to talk to people about what their old family photographs say to them about who they, and their country, are today. This week, Lucy Zoria, 24, a production assistant, tells her family's story from Kiev.

This article was first published by Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty as part of the My Ukraine project.

I've always been interested in the history of my mother's parents and grandparents. Their lives give you an idea of what it was like to be a member of the intelligentsia in Soviet times.

My mother came from a family of Polish Jews who were originally from Odessa.

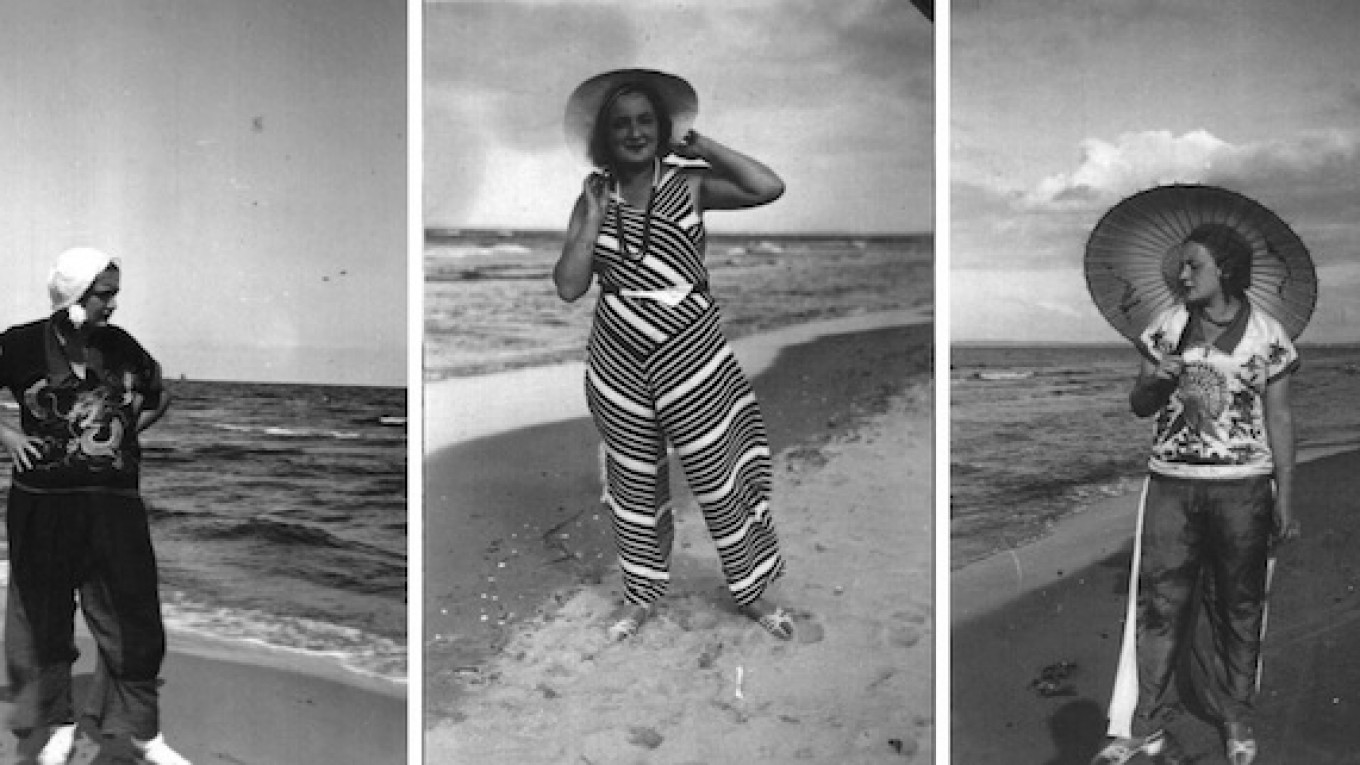

My great grandmother, Selena Shvartzman, grew up in a prosperous, very warm family. Her father was in the oil and gas business. She was an actress, and a bit of a character. We have a lot of pictures of her just posing in different fabulous outfits, and we still have one of her fur coats in a closet. I think she had fun.

She got pregnant with my grandmother, Asta, after having an affair with a Russian poet. Who this person is is still a source of great speculation for us.

But she ended up marrying a different man, Hryhoriy Pekker, a cellist who became one of the first Soviet musicians to tour abroad. They moved to Berlin in 1929 and seemed to have quite a nice life there.

They left shortly after Hitler came to power. They had ties to the Soviet Embassy, so they managed to avoid persecution as Jews.

Selena and Hryhoriy Pekker with baby Asta in Berlin, late 1920s.

From there, they moved to Moscow. I think the transition was difficult for my grandmother, especially during World War II, because she had spent her early years speaking German and other kids teased her for speaking the language of the Nazis. At some point, my grandmother gave up speaking German altogether. I never heard her speak it.

Hryhoriy's family, all musicians, died during the Leningrad Blockade. That haunted him. From then on, he always hoarded food. He even slept with bread under his pillow.

My great-grandparents were definitely part of the Soviet cultural elite, but never important enough for it to have terrible consequences. Still, there were many things that were difficult for them once they came back.

Hryhoriy faced pressure for being a "cosmopolitan," a person who wasn't sufficiently committed to the motherland, because he had lived abroad. And the fact that they were Jews made everything more difficult. Asta was denied university enrollment in Kyiv because she was Jewish. Eventually someone with connections intervened on her behalf.

It may have helped that my great-grandmother, Selena, remained very popular in social circles. There's a family story that she once met Leonid Brezhnev at a party in Kiev. He was Ukrainian himself, of course. He saw Selena drink vodka straight and thought, "Wow, what a woman!" Brezhnev took a huge liking to her, and even helped her and Hryhoriy secure two rooms in a communal apartment right in the center of town.

I think my grandmother inherited a lot of her mother's charm. She was the kind of person who had friends for life.

Asta Pekker with admirers in Kiev, 1950s.

Her upbringing was quite different from that of my grandfather, Anatoliy Sumar. His father was a commander in the Soviet Army, and he grew up in different countries, wherever his father was stationed -— Romania, parts of Asia.

Anatoliy started becoming interested in painting when he was a teenager. He never really had any formal training, but he read constantly and had a strong theoretical understanding of art history. He particularly loved the Picassos he saw in Moscow. He even named his son Pavlo, the Ukrainian version of Pablo.

He liked to learn on his own. He studied architecture and civil engineering at university, but he never even got a diploma, because he had grown a beard and refused to shave it off. The university wouldn't give him his degree as long as he had the beard. He was very stubborn that way.

Anatoliy Sumar, "looking very young and handsome and like an impressionist painter," according to his granddaughter.

My grandparents met at the Philharmonic here in Kiev. My grandfather used the artist's traditional line: "Let's meet again and I'll paint you!" They got married pretty quickly. It was quite scandalous at the time because she was older than he was and pretty old to be unmarried in the first place. She was 28 and he was 22. But it worked out.

Anatoliy liked to paint the things around him -— street scenes, windows, plants, street lamps. In 1962, he was included in an exhibit of works by young artists. The head of the Ukrainian Communist Party visited the exhibit and singled out my grandfather as an abstract expressionist.

This was usually enough to kill an artist's career, but my grandfather didn't mind. He was ready to give up painting at that point anyway. He went on to hold other jobs in architecture and design. He really only painted for a total of about six years.

But being singled out by the Communist Party boss really contributed to his fame. People started dropping by Anatoliy and Asta's apartment to meet The Artist. He was a very severe person; he didn't like attention. But my grandmother was very hospitable. She was a literary editor and very well-read. They never locked their doors. People would drop by to see him but end up staying because of her. The painter Tetyana Yablonska came, the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko.

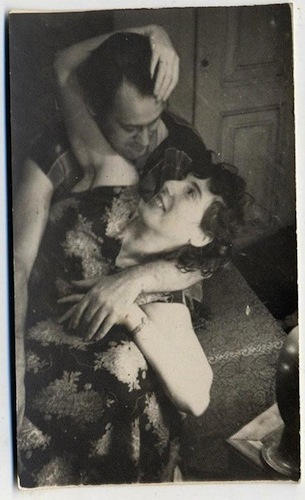

Anatoliy and Asta, Kiev, late 1950s.

Anatoliy started painting again in the 1990s and had his first exhibit in decades. I think it was only then that he finally understood that his art had a larger meaning. He died in 2006; Asta died in 2012. I feel that these are people who were greater than I am; I'm just here to keep their stories.

I spent some years growing up in the United States, but I really feel at home in Kiev. It's where my grandparents lived, where my parents live.

Life is harsher here, but there is an openness, a connectedness that you don't see in other places. People put a priority on friendships, on free time. Before Maidan, people thought in terms of when to leave and where to go. But now people are starting to believe they have a future here.

Lucy Zoria with a portrait of her grandmother, Asta, painted by her grandfather, Anatoliy Sumar, at the National Art Museum of Ukraine.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.