In the little more than a year since 2013, when Moscow first grew nervous over Ukraine's desire for European integration and President Vladimir Putin presented a set of initially fair and reasonable claims to the West, the world has watched as the Russian leader has put this country into an increasingly deplorable position.

In light of the cease-fire agreed at yesterday's Minsk meeting, you can now breathe a sigh of relief and know that the vicious cycle of escalating violence has ended and you can thank a group of truly extraordinary leaders for our collective good fortune.

However, as everyone who viewed the official footage of German Chancellor Angela Merkel's earlier meeting with Putin in Moscow on Feb. 6 could see, she did not look very confident about the chances of a peaceful resolution to the crisis.

It is easy to understand why: The German chancellor had been flying between countries in the northern hemisphere for several days in an attempt to avoid what her more straightforward colleague, French President Francois Hollande, bluntly referred to as war.

It has become fashionable in recent days for commentators to suggest that people are exaggerating the importance of this whole Russian-Ukrainian-Western story, that it is not a prelude to a global conflict, that it is only one of dozens of such local disputes in the world and that it is pointless to compare modern Russia with the Soviet Union.

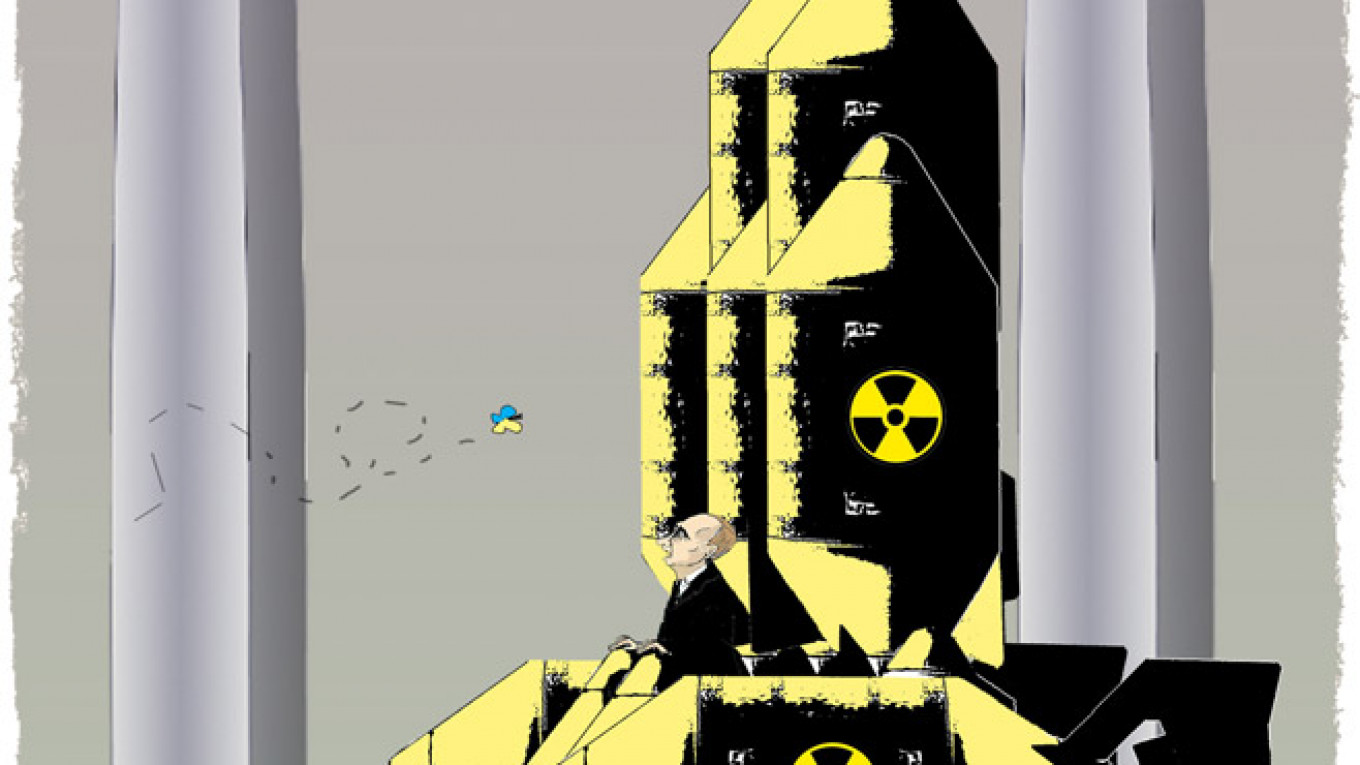

In truth, such a comparison would not favor Russia, with the exception of one thing: Russia inherited the Soviet Union's entire nuclear arsenal, and even managed to enlarge it a bit in the years since.

So, of course, this is not a local conflict, but a potentially very dangerous situation in which a country with enough nuclear weapons to destroy the world several times over — as we all remember from our grade school days — stands on the verge of a full-scale military deployment.

Merkel's nervous expression is also perfectly understandable: Any one of us who fully appreciates what is at stake here wears approximately the same look on our face every time we read the newspaper or watch the evening news.

But there are probably some additional reasons behind her unease.

Western politicians must surely realize that much of what Putin is asking for — if, indeed, state-controlled media are reporting his words faithfully — is fair and reasonable. And that means, if the situation does escalate, the West cannot, in good conscience, blame Putin for everything that happens.

Merkel, Hollande and U.S. President Barack Obama know one thing: At the root of all this monstrous and bloody story is the fact that the West lied to Moscow 25 years ago when it said it would not expand NATO even one inch to the east if the Soviet Union agreed to the unification of Germany.

If you take a moment to consider how far east the military and political boundary of the West now lies, you can probably understand why some people view that as underhanded and a gross injustice. One such person is President Vladimir Putin, who happens to posses substantial capabilities in the area of planetary destruction.

All of the counterarguments are well-known. Yes, not all in the West were in favor of German unification, and that made it difficult for Moscow to demand something from the West in exchange for its cooperation.

Rather than relying on a backroom promise, the leaders of that time ought to have written up a treaty stipulating that NATO would not expand. And yes, the newly independent Warsaw Pact states and former Soviet republics do have the right to choose which international organizations they join.

However, in deciding to expand during the euphoric years after the Soviet Union's collapse, the West neglected one of the fundamental rules of realistic international policy — the rule of the balance of power.

Obama, Merkel and Hollande all know that it was the West that disrupted the balance of power, even if their distant predecessors were the ones responsible. If they do not understand that, they are unfit for their posts. If they do understand, it explains the tortured expressions on their faces.

After all, they are compelled to constantly place all of the blame on the side that sincerely and with good reason believes that, in this case, it is only responding to an attempt to impinge upon its legitimate national interests.

That is the story the Russian president can and will successfully tell in every country that has its own issues with the West. Egypt, that showed its support by displaying portraits of Putin during his visit on Monday, is hardly the only country in the world to feel that way. There is a large and eager audience for anyone who is willing to speak of Western underhandedness, cunning and evil, and how it conflicts with the non-Western forces of good.

It is difficult to deny that Putin has these legitimate complaints. However, that represents the limit of his moral high ground.

The West really did take full advantage of its opportunity to violate the balance of power in the world and must now busy itself with overcoming the negative consequences.

At the same time, what has Russia done to restore that imbalance apart from annexing Crimea and fueling the war in eastern Ukraine? What has it done to live up to the dream that Russia's new leaders held in the early 1990s — namely, that this country would become a new point of attraction and a force for reintegration among the former Soviet republics? What is Russia offering now to compensate for all that it failed to accomplish over the past 20 years?

The answer: very little. And ultimately, that is even more important than the fact that the West did not use the opportunity it had in the 1990s to positively influence the changes taking place in Russia.

And now, when Russia no longer produces much of anything besides raw materials, it has become fashionable to talk about "relying on our own strength." Of course, this state of affairs suggests that the West was not perfect in supervising Russia's reforms.

But even if that is true, the blame cannot rest on the foreign advisers. Russia itself squandered an enormous number of God-given petrodollars to build a hideously aggressive kleptocracy with dysfunctional courts, schools and hospitals.

If, during his 15 years in power, Vladimir Putin had built up a fully functional and independent court system, instituted reforms to education, equipped hospitals, built roads and improved cities rather than funding the enormously expensive and short-lived Winter Olympic Games in Sochi, it is very possible that Putin's arguments concerning Western injustices would have found an audience in more than just Egypt and a handful of other disgruntled developing states.

And it is equally possible that, had Putin taken that path, Ukraine, along with other former Soviet republics, would have opened its arms to Moscow 10 or more years ago.

But Russia's current condition is very different, and all of Moscow's talk about the glaring injustices of the West therefore sounds disingenuous. Whether or not the war in Ukraine escalates, Moscow's approach will only deepen its isolation, nearly eliminate any chance of political and technological modernization and perhaps even lead once again to this country's collapse.

Placing all of the blame for this on the West would be just as pointless as blaming Russia alone for the crisis in Ukraine. And regardless of the meeting in Minsk, the main challenge is not to assign blame to either Russia or the West, and not even to change Russia's course and the country itself to at least partially reverse all of its lost opportunities of the last 20 years. The real challenge is to ensure that the current crisis does not pull half of the planet into an ever-widening abyss.

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 15 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.