President Vladimir Putin's reported distance-diagnosis as having Asperger's syndrome makes him the latest in a long line of Russian rulers whose actions and behavior the world has sought to explain as being the result of a physical or psychological ailment.

Ivan the Terrible

Ivan the Terrible (1530-1584) perplexed both his own boyars and his Western counterparts — not least Queen Elizabeth I of England, whom he wanted to marry — with his unpredictable behavior. By the 19th century, psychiatrists had begun to take an interest in whether his tyrannical and erratic behavior (such as beating his son and heir to death) was the result of a mental illness.

Based on first-hand accounts of his reign, both Western and Russian historians diagnosed him as suffering from paranoia. The Western historian Richard Hellie said he exhibited the classic signs of delusions of persecution, megalomania and erotomania (believing others to be in love with him), and that by 1566, he was "totally insane."

Historians have offered multiple theories for what may have triggered his state of mind, ranging from an unhappy childhood and grief over the death of his first wife, to alcohol abuse in later life or advanced syphilis.

Peter the Great

Peter the Great (1672-1725), the giant, hands-on reformer-tsar, known for his eccentric behavior such as pulling out his courtiers' teeth and collecting "freaks of nature" from around his empire, suffered from seizures, though there is little reason to believe they affected his behavior. In the book "Peter the Great: His Life and World" (1981), historian Robert K. Massie described the affliction, which first manifested itself when the tsar was in his early 20s.

"When he was emotionally agitated or under stress from the pressure of events, Peter's face sometimes began to twitch uncontrollably. The disorder, usually troubling only the left side of his face, varied in degree of severity … [sometimes] there would be a genuine convulsion, beginning with a contraction of the muscles on the left side of his neck, followed by a spasm involving the entire left side of his face and the rolling up of his eyes until only the whites could be seen. At its worst … the convulsion ended only when Peter had lost consciousness."

Most likely, Massie concluded, Peter suffered from "focal epileptic seizures, among the milder of a range of neurological disorders whose most severe form is grand-mal epilepsy."

While historians over the years have considered childhood traumas (such as witnessing a bloody revolt) and excessive drinking as possible causes of the ailment, most — including Massie — ultimately came to the conclusion that the mild epilepsy was the lasting effect of severe encephalitis, or inflammation of the brain, brought on by a very high fever that Peter suffered shortly before the fits began.

Lenin

Attempts to understand the psychological motives behind Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924), who ruthlessly spearheaded the Bolshevik Revolution that upturned Russia in 1917, have yielded suggestions that Lenin was driven by a desire for revenge for the death of his older brother Alexander, who was hanged for plotting against the Tsar Alexander III in 1887. One recent article diagnosed Lenin as having posttraumatic embitterment disorder as a result of this incident.

In addition, a team of Israeli doctors has claimed that the real cause of Lenin's death was neurosyphilis, not the consequence of a series of strokes as was officially recorded, and that the advanced stage of the disease may have caused his personality to change.

The revolutionary's contemporaries reported that Lenin, who is believed to have suffered from syphilis for many years before his death, became quick-tempered, irritable and sometimes lost self-control.

"His [Lenin's] private business affected the lives of millions because of his illness, his inability to lead the country at a crucial time," Yoram Finkelstein, one of the doctors who worked on the report, has been cited as saying.

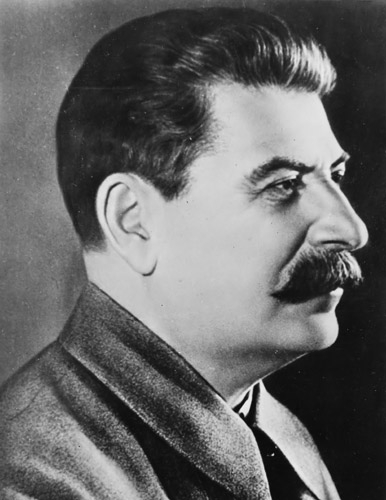

Stalin

Attempts to use psychology to understand the actions of Russia's bloodiest ruler, Soviet dictator Josef Stalin (1879-1953), usually revolve around the idea that the merciless and sometimes paranoid Georgian was essentially the result of a classic bullying legacy: As a child, Stalin was brutally beaten by his father, a violent drunk.

"No psychoanalytical sophistication is required," concluded the historian Robert Service. "Like many who have been bullied in childhood, Josef grew up looking for others whom he could bully."

In 2011, a physical reason for Stalin's behavior was put forward. When parts of the diary of one of his doctors were published, it emerged that the ruler had suffered from atherosclerosis — a build-up of fatty materials in the arteries — of the brain.

"I would suggest that the cruelty and suspicion of Stalin, his fear of enemies... was created to a large extent by atherosclerosis of the cerebral arteries," Dr. Alexander Myasnikov wrote in his diary, which had been kept secret until Moskovsky Komsomolets newspaper published extracts from it.

"Stalin may have lost his sense of good and bad, healthy and dangerous, permissible and impermissible, friend and enemy. Character traits can become exaggerated, so that a suspicious person becomes paranoid.

"The country was being run, in effect, by a sick man," he concluded.

Yeltsin

The public behavior of Boris Yeltsin (1931-2007) toward the end of his rule was a source of fascination for armchair psychologists both inside and outside Russia. His slow, slurred speech, unsteadiness on his feet and unhealthy appearance prompted speculation that the president was either often drunk or suffering from Parkinson's or Alzheimer's diseases.

Psychiatrist Mikhail Vinogradov said publicly in 1998 that Yeltsin was showing signs of Alzheimer's disease and proposed that the president undergo a psychiatric evaluation, saying: "Boris Nikolaevich is clearly incapable of properly assessing whether he is physically and mentally capable of doing the job."

In his memoirs, Yeltsin himself explained away some of his more surprising actions, such as famously seizing the baton to conduct a military orchestra in Berlin in 1994, as down to him having been drunk, and it is now generally accepted that alcohol, and not a degenerative illness, was to blame.

Contact the authors at s.collinson@imedia.ru and newsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.