Yevgeny Buryakov, a Russian banker arrested in the United States under charges of economic espionage, is not Russia's first economic spy. In fact, he stands at the forefront of a great tradition of economic and industrial espionage waged by the Soviet Union's intelligence service, the KGB.

These activities were intended to remove the West's technological advantage by stealing cutting-edge research and designs, ensuring that Soviet technology and industry never fell far behind.

Under the leadership of President Vladimir Putin, himself a former KGB officer, Russia's Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) has continued the work of its Soviet predecessors.

“What struck me most was how traditional the approach used by the SVR seems to be,” according to Russian security services expert Andrei Soldatov.

According to Soldatov, one need only to replace “Russian” with “Soviet,” and the case of Vneshekonombank official Yevgeny Buryakov looks just like it would in 1985. The only exception is that instead of a Russian bank, he would have been a member of a Soviet trade delegation

In the spirit of the glory days of Soviet economic intelligence gathering, here are the KGB's three most iconic success stories.

1. Stealing the Atomic Bomb

The first Soviet atomic bomb test in 1949.

Soviet leader Joseph Stalin is said to have known about the U.S. Manhattan Project, which created the first atomic bomb, long before U.S. President Harry Truman was told of its existence.

In fact, both the U.S. and British atomic bomb projects were so littered with KGB informants that they knew of the project's existence before the FBI did.

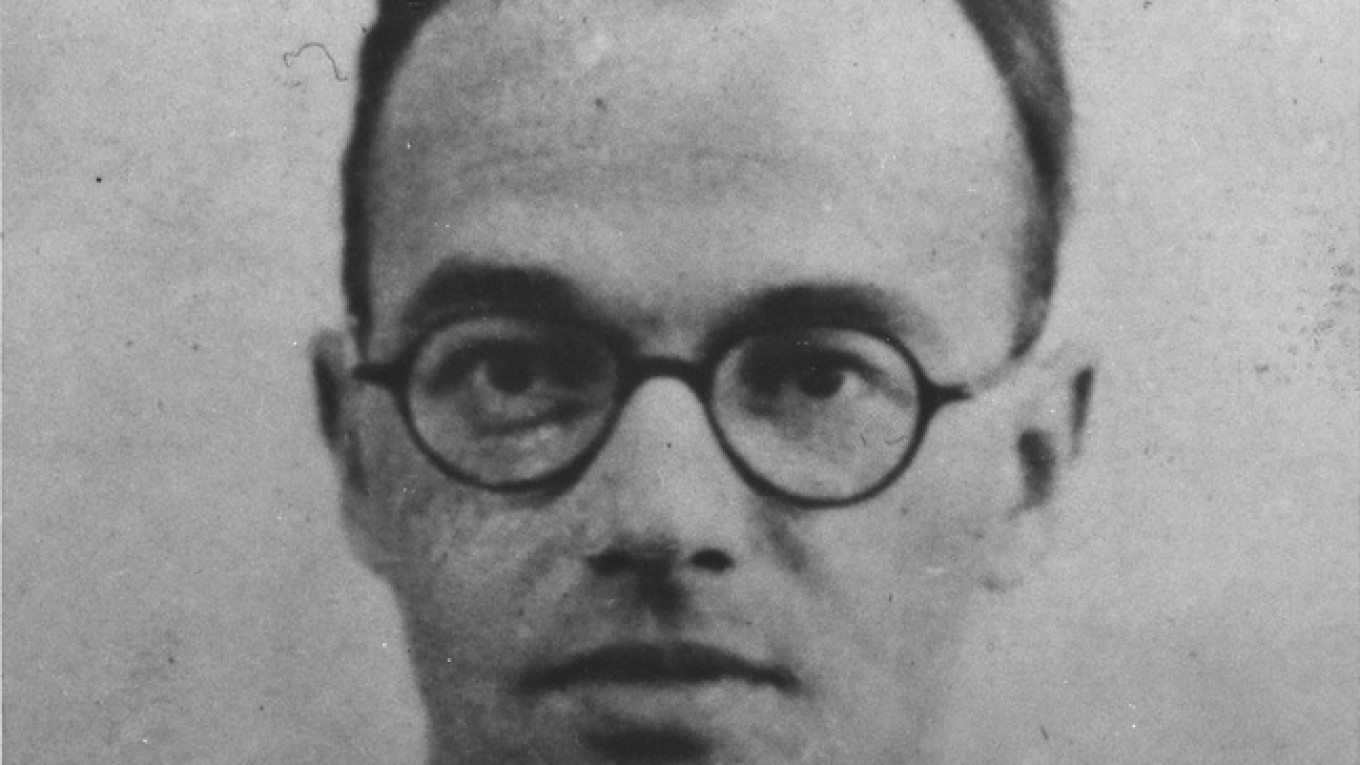

One of these sources, theoretical physicist Klaus Fuchs, was eventually identified by the FBI as one of the most valuable atomic spies in Stalin's arsenal. As a lead scientist on the Manhattan Project, he passed along critical scientific information to Russian intelligence officers.

Information provided by Fuchs and others allowed the Soviets to complete an atomic bomb two years ahead of schedule, shocking the world with its test detonation in August 1949. The Cold War arms race had begun.

2. Copying the Concorde

The Tu-144 in flight, because if its likeness to the Anglo-French Concorde, Western observers dubbed it "the Konkordski."

The supersonic Concorde airliner, for decades the pride of the British and French aerospace communities, was another target of Soviet industrial espionage. Like the atomic bomb theft, the Soviets got their hands on pioneering research by recruiting an inside man.

The spy, who was only identified by the code name “Ace,” gave the KGB over 90,000 technical documents on the Concorde jet's design, as well as those of other advanced Western aircraft of the day, according to a 1999 BBC news report.

The result of Ace's work was most visible in the Tupolev design bureau's Tu-144 supersonic jet airliner. It looked so much like the iconic British-French design, that when it started flying in the 1970s observers quickly dubbed it the “Konkordsky.”

3. Reproducing the Space Shuttle

Soviet space shuttle Buran on display at the 1989 Paris Air Show. Like the U.S. space shuttle, it was transported on top of a large airplane, in this case, an Antonov An-225.

The U.S. space shuttle was considered by many observers to be the crowning achievement of the U.S. aerospace industry — an expensive and monumental effort that brought together years of aircraft and spacecraft research into one hybrid vehicle.

Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev wasn't so enamored with it. Instead of technological triumph, he saw a dastardly space bomber. In 1974, he ordered the Soviet Union's Military-Industrial Commission to task the space industry with creating their own.

A large portion of the research and design work required to build the U.S. space shuttle was available on the fledgling U.S. government intranet and the KGB needed only to get onto the network, according to a 1997 NBC news report.

Thus began one of the largest and most successful Soviet industrial espionage projects of the Cold War — and perhaps the first documented instance of online espionage. Russian scientists discovered that the U.S. space shuttle was not a bomber but built their own version of the shuttle anyway, called Buran.

Unfortunately, the collapse of the Soviet Union only left time for one test flight for the Soviet Union's Buran in 1988. The economic turbulence that followed killed the program.

Contact the author at m.bodner@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.