BRUSSELS/KIEV — European Union foreign ministers agreed on Thursday to extend existing sanctions against Russia by six months but were still debating whether to impose new measures, with the new government in Greece sowing uncertainty that exasperated its allies.

The worst fighting for five months raged on in eastern Ukraine, with pro-Russian rebels who have disavowed a ceasefire pressing to encircle a government-held garrison town.

Britain said it scrambled fighters after Russia flew long-range bombers near its air space, disrupting civilian aviation. It summoned the Russian ambassador for an explanation.

Foreign ministers of EU member states held emergency talks in Brussels on Thursday, called after the rebels launched a new advance last week. NATO says the advance, including the shelling of the port of Mariupol that killed 30 civilians on Saturday, is backed by Russian troops, which Moscow denies.

Leaders of several EU countries said the new offensive must be met both by an extension of existing sanctions due to expire in coming months and by new stronger measures to increase pressure on Moscow.

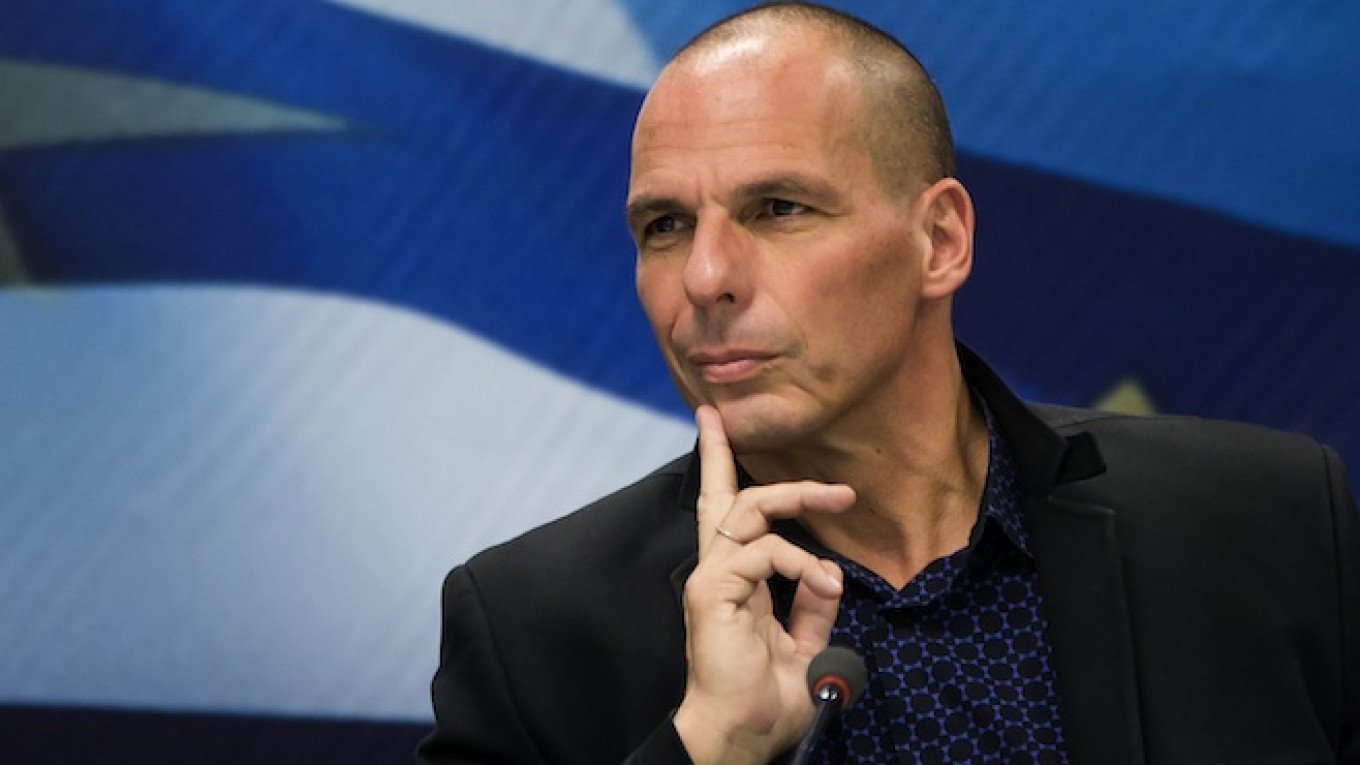

But Greece's new Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, elected this week, has complained about the bloc making decisions without consulting his government first. Officials in his government have given conflicting statements about their position, with some indicating Athens could oppose more sanctions.

An EU diplomat said agreement was reached on a six month extension of asset freezes and travel bans against individuals and firms, but talks were still continuing about adding new names to the sanctions list and preparing new measures.

Greece's new Foreign Minister Nikos Kotzias was giving nothing away in public. Asked by reporters on his arrival what Greece's intentions were, he said: "I have to make negotiations … have a good time."

Others countries, in particular Germany, did not hide their frustration: "It is no secret that the new stance of the Greek government has not made today's debate any easier," Germany's Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier said.

Steinmeier later held a 20-minute meeting with Kotzias and a German official said Berlin was "less concerned than before."

Russian Bombers

The appearance of Russian bombers near Britain was a repeat of a pattern that several Western countries reported late last year, with Moscow flying its warplanes close to the territory of NATO states.

On the ground in eastern Ukraine, there was fighting around the town of Debaltseve, a town of about 26,000 people on an important road and rail route linking the two main rebel strongholds. The town is still held by government troops but surrounded on three sides by rebels. Power and water have been cut off and civilians trapped in cellars.

"Everything is bad in Debaltseve. People are living full-time in shelters without fresh air," said Natalia Voronkova, a volunteer who has been helping residents escape. "Children are getting sick and there is a great need for medicine."

The rebels say they had no choice but to repudiate the five-month-old ceasefire and advance — effectively restarting a war that has killed 5,000 people — because government artillery in range of their cities had been shelling civilians.

Kiev says the rebel advance is an attempt to capture more of its territory, backed by as many as 9,000 Russian soldiers on the ground. Its biggest fear now is an all-out assault on Mariupol, a government-held port of 500,000 people.

Test of Unanimity

Thursday's meeting is the first big test of the hard-won unanimity that European officials, led by Germany, achieved last year to punish their biggest energy supplier Russia over its actions in Ukraine, which aspires to join the EU.

EU officials had already drawn up an agreement in advance of the meeting for the ministers to endorse which would extend sanctions by six months and authorize new steps. These could include capital markets restrictions making it harder for Russian companies to refinance and possibly affecting Russian sovereign bonds, EU officials have told Reuters.

Ukraine's foreign minister, Pavlo Klimkin, in Brussels to make Kiev's case, said EU ministers had told him they were "ready to prepare a bold and robust statement about supporting Ukraine, about further ideas how to increase pressure on Russia also in the sense of possible restrictive measures." He said he would meet the Greek foreign minister later on Thursday.

What was still not clear on Thursday was whether Greece was taking an independent line over sanctions because it disagreed with them, or whether Tsipras's new government was insisting mainly on the principle that it be consulted, perhaps as a way of showing independence ahead of important debt talks.

Tsipras was elected on a vow to repudiate the austerity economics championed by Berlin and imposed by Brussels as a condition of a loan bailout. Without new loans from the EU, Greece would default on its debt and could be cast out of the euro zone and the EU itself.

The new Greek leader has not made his position on Ukraine clear in public. His Syriza party has its roots in leftist movements, some of which were sympathetic to Moscow during the Cold War, and Russia's ambassador was the first foreign official Tsipras met after taking office on Monday.

But Greece is also a NATO member that has long treasured its role in the Western alliance. It shares Orthodox Christianity with both Russia and Ukraine, and many Greeks sympathize with both countries.

Greece's energy minister said on Wednesday that Athens was against further steps against Moscow. On Thursday, the new finance minister suggested in a blog post that Greece's stance had been misinterpreted.

Foreign Minister Kotzias said on Thursday that some EU peers had tried to present Greece with an unacceptable fait accompli by issuing a statement on Ukraine without Greece's agreement. He also explicitly rejected any link between Greece's position on Russian sanctions and the debt talks.

The suggestion that Greece might be using its support for sanctions as a bargaining chip for debt relief angered some ministers, particularly those of the Baltic nations adjacent to Russia that have been most alarmed by events in Ukraine.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.