Visitors to the new exhibit at the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre enter through a dark corridor. Hundreds of names are written in different shades of gray on walls and seem to fade in and out of the darkness.

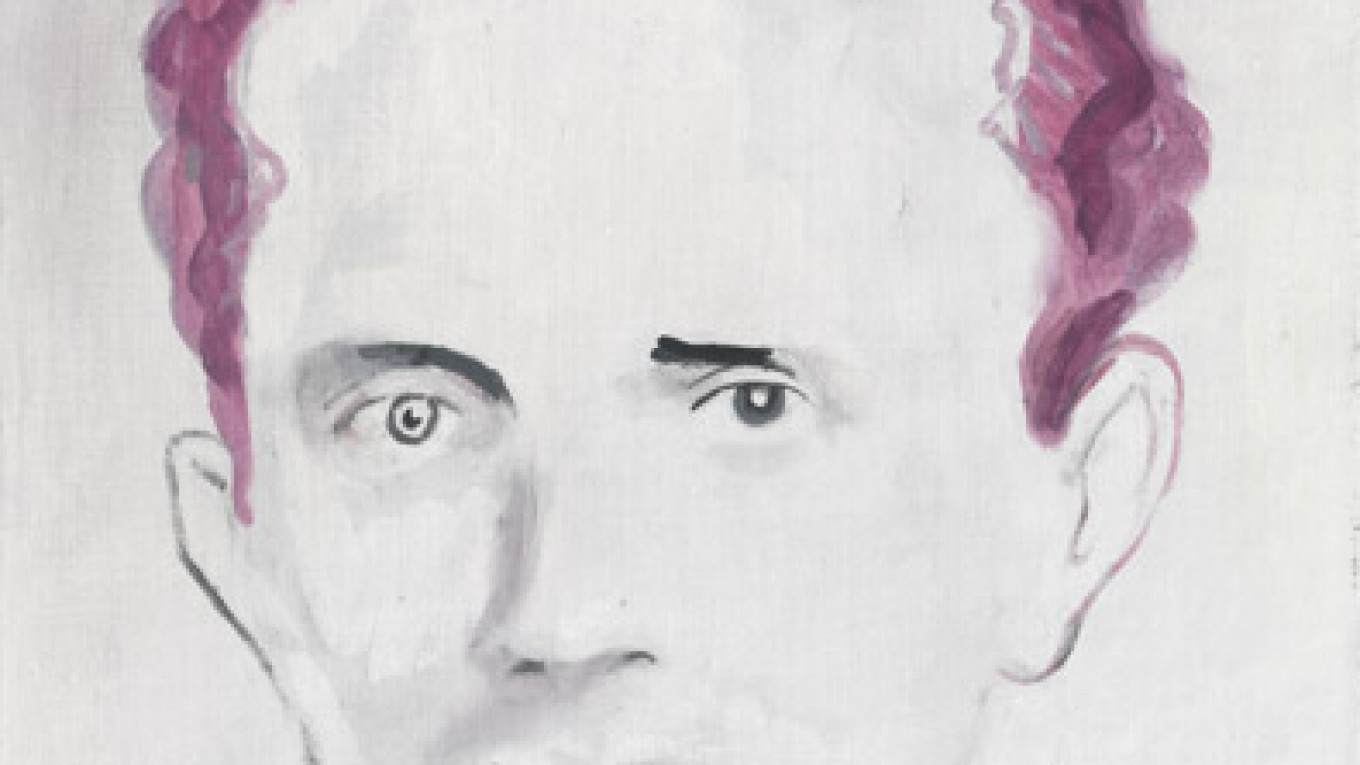

In the exhibit itself, some names of Holocaust victims are given faces in portraits by Belgian artist Jan Vanriet. "Each painting is an individual," said Vanriet. "It is the personality that dictates the painting."

The exhibit, called "Man and Catastrophe," opened Tuesday to mark Holocaust Memorial Day and the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz and brings together the portraits of Vanriet, modern landscapes of concentration camp areas by Russian photographer Yegor Zaika and blueprints and documents from Auschwitz.

"Each part of the exhibit puts forward the Holocaust from a different point of view: [from the] murder, the victim and today's perspective," said curator Maria Nasimova.

One part of the exhibit, called the "Architecture of Death," shows how Auschwitz was designed by the Nazis. Nasimova called it the most "most important part of the exhibition for her" as it showed how the "machine for murder" was created and how the Nazis were "humans who surrendered their morality."

President Vladimir Putin was one of those to attend the exhibit opening.

Vanriet's pictures are of people whose mug shots are now held in the Kazerne Dossin archive which stores documents related to the Holocaust in Belgium and northern France.

"These are portraits from the past, but they are also portraits for today, as people are still persecuted for what they believe and for being who they are," said Vanriet in a speech at the opening.

Many of the people depicted in the paintings, made between 2009 and 2012, are originally from Eastern Europe and Russia and Vanriet said that was important to him. "Their roots are here. It is an honor to return them to where they are from."

Vanriet's series is called "Losing Face" and these paintings, said Anna Treskunova, executive director of the museum, document the loss of character, the loss of lives and the loss of the faces of these people.

"It returns these faces and these people and it reminds us that they are humans," said Treskunova.

The museum, as its name suggests, is in part dedicated to building bridges between all people. Similarly, the exhibit contains a universality, depicting the Holocaust as a crime concerning all of humanity. "Everyone can relate to it because it is art," Nasimova explained, "how people react to it will be different, for example a child will understand a painting differently to an adult."

The brightly colored photography of Zaika show how areas connected to the Holocaust —Auschwitz, Lublin, Treblinka — look today.

"Every since childhood I thought and drew about the second world war. It was part of my upbringing," he said, "As an adult, I wanted to present a current and living picture. We live in color and so this should be presented in color too."

The photos show scenes which could be anywhere and Zaika writes by the photos that the "lack of a specific reminder should serve as remembrance." The everyday can be infused with impending death, he writes, as when the Nazis would play music in camps or place a banal object in a room to lull victims into a sense of security.

The museum has a host of events to accompany the exhibit, including film shows and concerts with music composed by those who died in the camps.

"Man and Catastrophe" runs until March 1. Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre. 11 Ulitsa Obraztsova. Metro Marina Roshcha. Tel. 495-645-0550.

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.