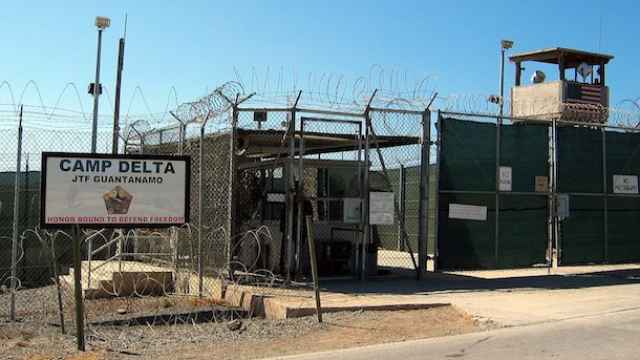

WASHINGTON — Three Yemenis and two Tunisians held for more than a decade at the U.S. military prison at Guantanamo have been flown to Kazakhstan for resettlement, the Pentagon said on Tuesday, the latest in a series of prisoner transfers aimed at closing the facility.

The transfer of the five men followed a recent pledge by President Barack Obama for a stepped-up push to shut the internationally condemned detention center at the U.S. naval base in Cuba where most prisoners have been held without being charged or tried.

The U.S. government has moved 28 prisoners out of Guantanamo this year — the largest number since 2009 — and a senior U.S. official said the quickened pace would continue with further transfers expected in coming weeks.

Kazakhstan's acceptance of the five followed extensive negotiations, the official said. Though the oil-rich central Asian state is an ally of Russia, it has cultivated areas of economic and diplomatic cooperation with the West.

The men sent to Kazakhstan, a majority-Muslim country, were identified as low-risk detainees cleared long ago for transfer. With their removal from Guantanamo just before the new year, the detainee population has been whittled down to 127.

More than half of the remaining Guantanamo detainees are from Yemen, but Washington is unable to send them home because of the chaotic security situation there.

Obama continues to face obstacles posed by Congress to the goal of emptying the prison before he leaves office, not least of which is a ban on transfer of prisoners to the U.S. mainland.

All five men were detained on suspicion of links to al Qaeda or allied groups, but the U.S. official said investigations had determined they "could be described as low-level, if even that."

Resettlement Efforts Gather Steam

The Pentagon identified the Yemenis as Asim Thabit Abdullah Al-Khalaqi, Muhammad Ali Husayn Khanayna and Sabri Muhammad Ibrahim Al Qurashi. The Tunisians were named as Adel Al-Hakeemy and Abdullah Bin Ali Al-Lufti.

Other countries that have accepted Guantanamo detainees for resettlement this year include Uruguay, Georgia and Slovakia.

The prison was opened by Obama's predecessor, George W. Bush, after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on the United States to house militant suspects rounded up overseas.

"I'm going to be doing everything I can to close it," Obama told CNN in an interview broadcast on Dec. 21, renewing a pledge he made when he took office in 2008.

A key thrust of the strategy is the administration's outreach to a range of countries it hopes will take in more of the roughly 60 prisoners already approved for transfer.

Clifford Sloan, Obama's outgoing State Department envoy on Guantanamo, led negotiations for the Kazakh deal. It was not immediately known whether Obama played any personal role.

Among the prisoners sent to Kazakhstan, Lufti, 49, was detained in Pakistan and held at Guantanamo for nearly 12 years, according to a database of government documents compiled by the New York Times and National Public Radio.

He was accused of links to Tunisian militants when he lived in Italy in the 1990s, but he denied this. He has heart problems that led authorities to recommend his transfer as early as 2004.

One of the Yemenis, Khalaqi, 46, had been implicated by John Walker Lindh, an American captured in late 2001 working with the Taliban, as having fought with al Qaeda in Afghanistan, according to the documents. But Khalaqi denied any involvement.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.