Russian authorities are facing some unpalatable options as they try to keep the economy afloat — unless they can persuade President Vladimir Putin to curb massive military spending.

Officials fear that without limiting the defense budget, the government will have to raise taxes, increase the pension age or print money to prevent the state deficit from running out of control.

Despite a crisis brought on by diving oil markets and Western sanctions, they believe Russia can muddle through next year provided the price of crude, its dominant export earner, holds near current levels.

But even at $60 per barrel, the present oil price is little more than half what the Kremlin needs to balance the budget, and it is quickly running out of money.

Without radical action, the officials are much less confident about 2016-17 — and even sooner, should global oil prices continue their slide toward $40.

One senior government source expressed concern about the effects of an unchecked deficit on one of Russia's two funds built up from past oil income.

"If no spending is cut and revenue risks persist, we will have a deficit of 4 trillion rubles. The Reserve Fund will be spent within 18 months," he said. "In 2016 we will have no resources to meet our budget obligations. Not to mention 2017."

At current exchange rates, 4 trillion rubles equates to about $70 billion, not far from the $89 billion that the Reserve Fund now holds.

Sanctions imposed by the European Union and United States over Moscow's role in the Ukraine crisis have deepened the problems: foreign investment is down sharply, more than $100 billion has fled abroad this year, Russian firms and banks have lost access to international capital markets and privatization plans are on hold.

The Central Bank has had to spend heavily from its reserves, which have dropped to just below $400 billion from $510 billion at the start of 2014, to arrest a steep slide in the ruble.

Defense Drain

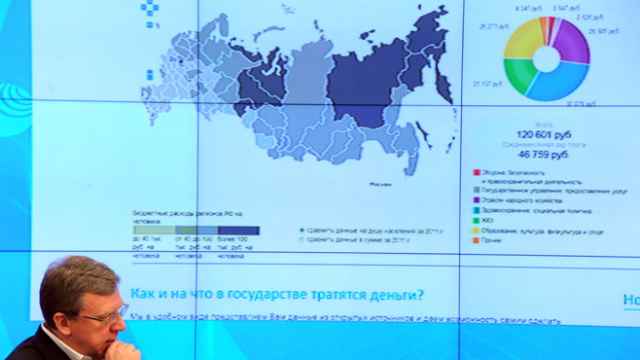

Spending will be cut 10 percent next year, but Finance Minister Anton Siluanov said last week that this was not enough to balance the budget. Expenditure is dominated by social and defense commitments, and Putin had set military investment as a priority even before the stand-off with the West began when Russia annexed Crimea from Ukraine in March.

Out of total spending of 13.96 trillion rubles (about $250 billion) in 2014, social benefits account for over 33 percent, and defense and security for 32.5 percent.

Next year, military spending will rise to 35 percent of the 15.51 trillion ruble ($265 billion) budget. That means about $100 billion for defense and security at today's exchange rates.

At the same time, the weaker ruble will lead to higher inflation next year by pushing up import costs, threatening Putin's reputation for safeguarding Russians' living standards.

The lion's share of social spending goes on pensions, and this will rise sharply due a rapidly aging population unless the government takes radical action by raising the retirement age from 55 years for women and 60 for men.

"Without cutting military spending and raising the pension age, we won't muddle through. What options do we have? Raise taxes and print money, which triggers a downward spiral of inflation and higher interest rates," the government source said.

'Dramatic Development'

In the shorter term, the biggest economic risk would be a further plunge in oil prices, even if they bounced back rapidly. A drop to $40 for just a few days could inflict great psychological damage.

Earlier this month, the ruble fell as much as 20 percent against the dollar in one day after oil plunged and the Central Bank raised its main interest rate sharply. The authorities were forced to impose informal capital controls to cool the panic and slow the flood of money out of the country.

Putin has said formal capital controls are not on the agenda. Officials are anxious to avoid such drastic action as this would inflict long-term damage on Russia's international financial reputation: investors will put money into a country only if they believe they can take the profits back out later.

"We won't introduce capital controls unless there is a dramatic development," said a top-level government source. "I don't know if $40 per barrel will trigger it. For our country it is very bad, it is a tragedy. But whether it will trigger capital controls or not, I just don't know," the source said.

In December 2008, oil fell during the global financial crisis to around $36 but even then Russia did not reinstate capital controls.

"This crisis is more psychological, more emotional than those we have seen in the past. But in principle, the situation is not very different from 2008. We can always switch to measures we used in 2009," the source said, naming state guarantees and direct funding of troubled companies among possible measures.

However, former Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin said the current crisis was different because of the sanctions. "To come out of the crisis, the government and the president should settle the conflict with leading powers, mainly Europe and the United States," he said last week.

However, the top-level government source held out little hope for an easing of tensions with Washington. "Relations with the United States are frozen," he said.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.