On Dec. 9, after long months of inspections and pressure from the authorities, the Justice Ministry included the Moscow School of Civic Education, or MSPS (previously named the Moscow School of Political Studies), on its list of nongovernmental organizations that "perform the functions of foreign agents."

That list now totals 18 NGOs. It includes organizations that are famous and authoritative both in Russia and abroad, organizations such as the PIR Center of lawyers for constitutional rights and freedoms, the Golos association, the Agora human rights organization, the Memorial human rights center, Soldiers' Mothers of St. Petersburg and Public Verdict.

Any NGO added to the registry of "foreign agents" immediately encounters serious problems. It faces more complex reporting requirements and is subjected to additional inspections and controls, but most importantly, many partnering organizations in Moscow and the regions become afraid and start canceling cooperation.

The term "foreign agent" carries a heavy stigma in Russia and sends a clear signal that the authorities look unfavorably on the organization and recommend that others shun it entirely — for their own good. Law enforcement bodies, intelligence agencies and the Federal Tax Service understand the label as a signal to step up pressure on the undesirable NGO, to badger and hound it with whatever hindrances and obstacles they can muster.

It is interesting to see which types of NGOs the Russian authorities have attacked:

The PIR Center — Since 1994 the organization has studied issues connected to the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons, international security, the spread of peaceful nuclear technology and international cooperation in this field.

MSPS — Since 1992 the school has provided civic education to young Russian elites and worked to build closer ties between Russian society and culture with other member countries of the Council of Europe.

Soldiers' Mothers of St. Petersburg — Defends the rights of servicemen and their families. It is currently investigating the Russian military's illegal participation in events in southern and eastern Ukraine.

Golos — Monitors elections and reveals instances of falsification and the violations of the rights of voters and candidates.

Memorial, PIR Center, Agora and Public Verdict — For many years, these organizations have defended people and organizations whose constitutional and legal rights were violated by the state, its agencies and officials.

It is easy to see that all of these organizations do the work that public institutions should ordinarily perform. They compensate for the institutional vacuum resulting from the inaction of parliament, the courts, prosecutors, electoral commissions and the education system, and from the weakened condition of the media and trade unions.

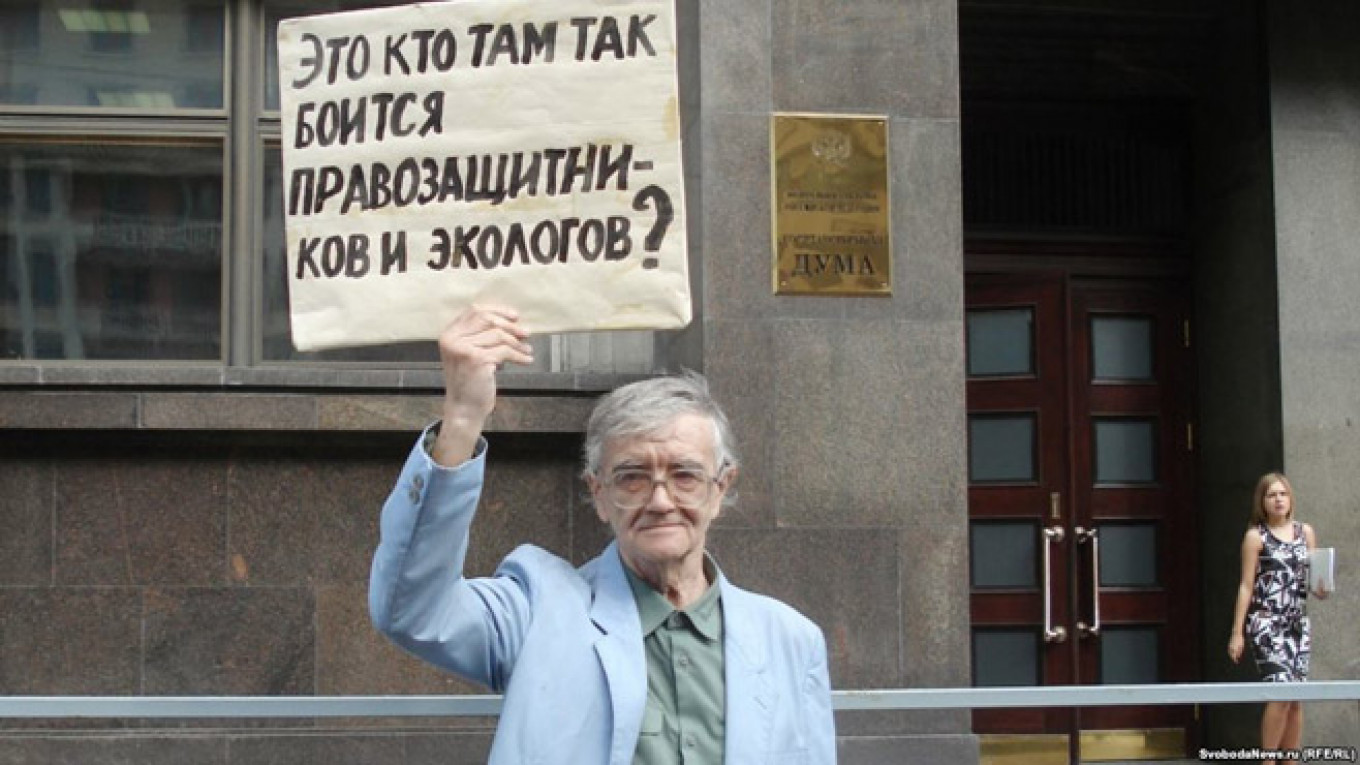

In the face of fierce Russian bureaucratic authoritarianism, independent NGOs assume the socially relevant functions of public control over military policy and military organization, the electoral process, laws, prison authorities and security services, the protection of citizens' legal rights, modern civic education and environmental protection.

Government and law enforcement agencies — which in recent years have managed to successfully suppress the independence and effectiveness of parliament, the courts, regional and local authorities, trade unions, electoral commissions, universities and the media — are now attacking effective and independent NGOs as the last bastion of civic engagement, the last remaining instrument giving society control over public officials.

Now NGOs are the last remaining barrier preventing the state bureaucracy from achieving complete and unfettered freedom to use and abuse the country's population and resources as it pleases. If the state achieves its desired "victory" over the sector, it will open the way to the final degradation of the state apparatus and political system and will reduce the efficiency of public administration to a minimum while maximizing the degree of corruption and legal abuses.

The Council of Europe's human rights commissioner, former first ombudsman in post-Franco Spain and adviser to the MSPS, Alvaro Gil-Robles, said this about the nature of authoritarian regimes: "The main focus of authoritarian regimes is the struggle against civil society." That is what we are seeing today in Russia.

The MSPS was founded back in 1992 by Yelena Nemirovskaya and Yury Senokosov to provide civic education to Russia's young elite who at that time had almost no understanding of modern political, social and economic processes. The Council of Europe provided strong and early support, such that the school's staff became leading Russian and foreign experts. They include Ernest Gelner, Alexei Salmin, Vladimir Lukin, Yury Levada, Robert Skidelsky, Dmitry Trenin, Richard Pipes, Lyudmila Alexeyeva, Yegor Gaidar, Ralf Dahrendorf and many others.

In its 22 years, the school has organized hundreds of high-level seminars in Russia and abroad, produced thousands of graduates and held seminars with the participation of hundreds of leading specialists. The MSPS became a unique Russian training institute for a modern and effective political, cultural and social elite. In fact, the Council of Europe established schools based on the MSPS model in 20 countries of Eastern Europe.

Many MSPS graduates now lead outstanding public and political careers as prime ministers, governors, city mayors, government ministers, parliamentary deputies, NGO directors and chief editors of media outlets. At the same time, MSPS has clearly distanced itself from any political or party affiliation, providing civic education to people of differing political views — from communists to United Russia and Yabloko party members.

What do the Russian authorities dislike about MSPS activities? They are irritated by the school's independence, its close ties to the Council of Europe with its emphasis on the protection of human rights, the popularity and effectiveness of its education programs, the liberal views of the school's founders and the majority of its specialists and the school's openness to Europe and the world.

But what most bothers them are the values the school defends and disseminates through its educational programs: citizenship, democracy, human rights, open society, grassroots activism, the social welfare state and the market economy. The Russian authorities are locked in a battle not with the school per se, but with the values it promotes.

Vladimir Ryzhkov, a State Duma deputy from 1993 to 2007, is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.