One of Russia's most celebrated contemporary artists, Pavel Pepperstein, took the prestigious Kandinsky Prize and a prize of 40,000 euros ($50,000) for a series of works called "Holy Politics."

Pepperstein did not attend the ceremony Thursday at the Udarnik, a former movie theater, and his prize was accepted by Vladimir Ovcharenko from the Regina Gallery, where "Holy Politics" was originally shown.

"It's our modern art … when we're all together, we can win," Ovcharenko said as he took away the Kandinsky statuette for Pepperstein. He said the artist, who rarely appears in public, could not be there because of visa problems, but did not explain further.

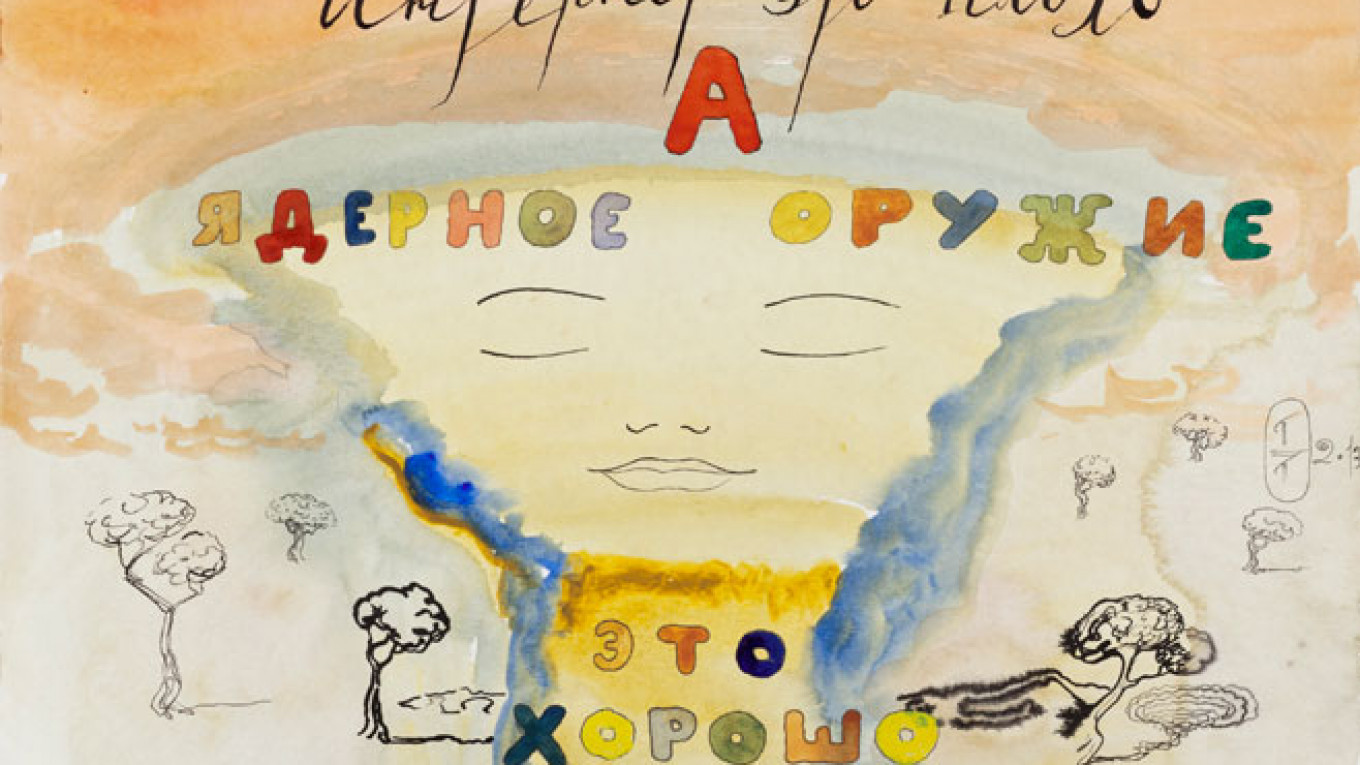

Pepperstein is one of the best known Russian contemporary artists and has been exhibited in the Tretyakov Gallery. He represented Russia at the 2009 Venice Biennale. "Holy Politics" comprises colorful, naive-looking, cartoon-like works including one cheerful-looking piece with the words: "The Internet is bad. Nuclear weapons are good."

Much of the art society saw it as visionary, others as absurd, a mockery, anti-political, an ironic take of European politics, art critic Olga Kabanova wrote in the Vedomosti newspaper Monday.

The Kandinsky Prize ceremony began with pounding techno music and a performance piece called "Razveska," which saw canvases hung from the back of the stage. Videos of nominees discussing the "museum of the future" were shown on the canvasses. Razveska has the dual meaning of "weighing" and also "hanging the show."

Some of Moscow's most well-known artists, curators and philanthropists packed the Udarnik, which the Kandinsky Prize organizers want to eventually turn into a museum, including billionaire Shalva Breus, the founder of the Breus Foundation for Contemporary Art, which started the award.

Founded in 2007, the Kandinsky Prize is Russia's most famous arts award with a particularly generous monetary prize: 40,000 euros for the "Project of the Year," and 10,000 euros for the "Young Artist. Project of the Year."

Soldatov accepting the award for his 13-minute video piece "Balthus."

Thirty-five nominees were chosen this year out of 418 applicants, 18 for the main prize, 12 for the young artist prize and five for the best theoretical art text. They were all shown at the Udarnik from Sept. 17 to Nov. 30. A shortlist of three in each category was later chosen.

The jury took only half an hour to decide who had won just an hour before the ceremony. Unusually for an award, artists can nominate themselves.

Irina Nakhova, last year's winner of the Project of the Year, handed out the award in the Young Artist category to Albert Soldatov, who won for a 13-minute video piece called "Balthus," which recreates poses of Balthasar Klossowski, or Balthus, the Polish French modern artist, who is most famous for his paintings of young girls in erotic poses.

The Guardian last year called Balthus, who died in 2001, "a figurative master in an age of abstraction, and one of the creepiest figures of modern art."

Born in 1980, Soldatov just snuck into the category, which is for artists under 35.

Soldatov has already exhibited at Triumph Gallery, one of Moscow's most famous galleries.

The third award given out on the night was for the best theoretical art text, which was won by Mikhail Iampolski for his work "Gnosis in Images." The award was handed out by art critic Andrei Tolstoy, and accepted by architect and artist Alexander Brodsky, himself a winner of the Kandinsky main prize in 2010.

"He is one of the cleverest and most learned men I know," Brodsky said. Iampolski, who now lives in New York and works in the comparative literature department at New York University did not attend.

The Kommersant newspaper wrote Monday that Brodsky's speech showed how much Iampolski means to him. It was also notable for being much longer than the speech he made when he won the Kandinsky himself.

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.