With relations between Russia and the West at a post-Soviet low, it is a good time to be reminded of the days when the United States and Russia were more friendly, when their citizens came together to talk, to fall in love, to marry and to decommission nuclear warheads with enough firepower to wipe out the world.

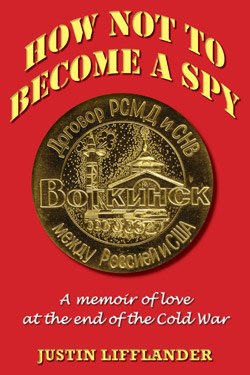

Justin Lifflander's excellent comic memoir, "How Not to Become a Spy: A Memoir of Love at the End of the Cold War," does exactly that by telling the fascinating story of how he ended up in the closed Soviet town of Votkinsk in the Urals as a decommissioning inspector in the late 1980s.

It was there that he met his future wife, who was supposed to keep tabs on him for the KGB. Almost three decades later, he still lives in Russia and is a citizen of both countries.

Lifflander, a former executive at Hewlett Packard and past business editor at The Moscow Times, had ended up in the Urals thanks to the landmark 1987 Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces treaty signed by U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in 1987.

Lifflander really wanted to be a spy.

In the foreword to the book, Lifflander writes that Reagan and Gorbachev did great things in that time — but haven't we heard enough about them frankly? His story is not a political history but "some entertainment and a bit of real life drama."

He does though make the serious point аbout the problems between his homeland and his adopted country.

"Intolerance, suspicion and sanctimoniousness run rife on both sides of the ocean," he writes, urging people to "challenge everything you think you know, take the time to dig deep, to scratch well below the surface, … and perhaps one day we can return to a time of open minds and open hearts."

The book is a very personal account of a pivotal moment at the end of the Cold War when two sides who had lived in fear of mutually assured destruction for decades allowed the enemy in.

When Lifflander finished college in the mid-1980s he went to meet what was then the enemy as a mechanic in the U.S. Embassy's motor pool.

Any expat who complains about life in Moscow in the 21st century can get a nice reality check as Lifflander talks about when ration cards were still being used.

He recalls Muscovites constantly asking foreigners why they had come to the country. A U.S. diplomat who was in the Soviet Union in the 1980s had a pat answer ready, Lifflander notes.

"Well, I don't wear a watch, and you have these large street clocks everywhere — very convenient. The local mustard is also good."

It was a good place for Lifflander to be as his ultimate goal was to become a spy. He is deprecatingly funny on his long-term ambitions to be a spy and his ultimate failure.

At the age of 12, he subscribed to Soldier of Fortune magazine; at the age of 14, he wrote to the CIA. The agency politely responded, saying it didn't have enrollment for schoolkids. So instead of spying on the Reds, he spied on his cute neighbor.

Once he arrived in Moscow, Lifflander was tasked with the all-important job of schoolbus driver, ferrying the children of diplomats and spies to and from the American school.

He yearned for a different world as any meaningful interaction with Soviet citizens was strictly forbidden at the time by both the Soviet authorities and embassy policy.

His chance came once Reagan and Gorbachev signed the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty on Dec. 8, 1987, and he jumped at the opportunity to become a weapons inspector.

That finally allowed him to interact with Soviets over the course of a two-year contract in the remote defense-industrial town of Votkinsk.

A monument to the missile treaty outside the Votkinsk factory in the Urals.

Votkinsk was the site of the Soviet decommissioning efforts, and 30 Americans were sent there to inspect the missiles to ensure that the treaty was being honored. The Soviets were allowed to deploy a similar mission at the Hercules missile plant in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Elements on both sides were not thrilled at giving their enemies such open access to the missile plants. One of Lifflander's Mormon colleagues at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow bemoaned the fact that the godless communists were coming to his home state, while the local KGB directorate in Votkinsk assumed that all the 30 Americans were spies.

Lifflander shows how two nations met each other for the first time realizing that Russians and Americans are more alike than they would prefer to admit. An essential part of this is Lifflander's courtship with his future wife, Alla.

The two eventually married, but not before politics and deeply rooted KGB suspicions of the eccentric American threatened to drive them apart for good.

The book should resonate with history buffs interested in a first-hand account of how the greatest arms-control agreement was implemented, but it is more importantly one that holds universal appeal to any expat in Russia and anyone who wants to "scratch beneath the surface" of Russians and Americans.

"How Not to Become a Spy: A Memoir of Love at the End of the Cold War" by Justin Lifflander can be bought on Amazon.com.

Contact the author at bizreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.