Ruble depreciation, Western sanctions and collapsing commodity prices have sent Russian companies' hard currency bonds tumbling to multi-year lows and there is very likely more stress ahead.

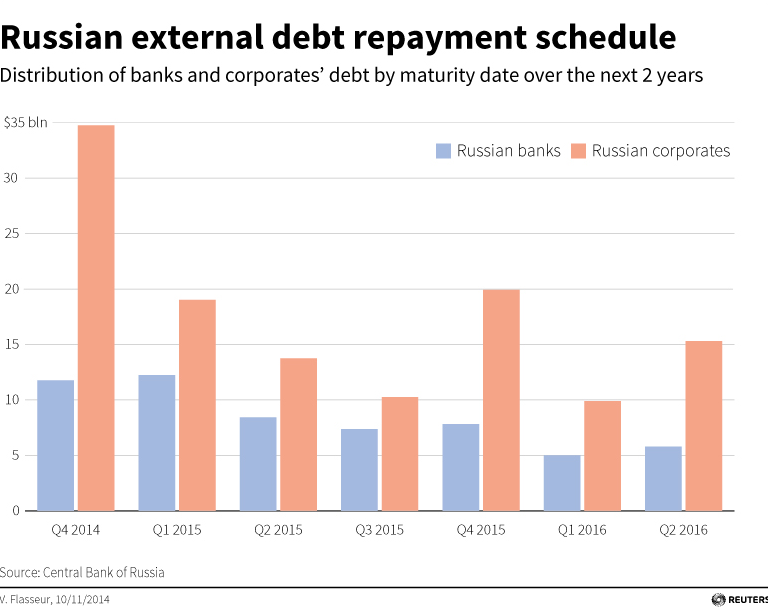

With around $650 billion in external debt, more than $100 billion due for repayments in the coming year and global capital markets effectively shut to Russia, companies, both private and state-run, are suffering.

Russian yield spreads on the CEMBI corporate debt index have almost doubled this year to around 788 basis points over U.S. Treasuries, though the index itself has barely budged. Since end-November a ruble rout has seen the spreads widen by more than 100 basis points, astonishing levels for mostly investment-grade credits.

However, a spate of corporate defaults looks unlikely because Russian authorities, with $400 billion in their coffers, will probably bail out most who run into trouble. Analysts also reckon most firms, especially exporters, are sitting on enough cash to meet short-term debt payments.

Yet there are few takers for the bonds, even among those who think defaults are unlikely.

"Is there a significant increase in credit risk and default risk? We think — not yet," said Sergei Strigo, head of emerging debt at Amundi. "But the uncertainty is so high that credit metrics don't matter anymore."

Strigo predicts firms will slash capital expenditure and put new oil exploration projects on ice but sees no real risk to debt repayments. But he is neutral on Russian company bonds, meaning that his holding does not exceed their weight in indexes.

"In these distressed situations what usually stops the process is large funds coming in to buy. But at the moment, on top of oil prices, you also have political risk which is very hard to assess," he added, referring to a potential tightening of sanctions imposed by the West over the Ukraine crisis.

Banks

For now, all sectors and companies, including those not subject to sanctions, are under the cosh.

Energy exporter LUKoil for instance, not sanctioned and benefiting from rouble weakness — has seen its 2017 dollar bond fall 12 cents from mid-year levels. State-run Rosneft's 2022 bond is trading at 76 cents in the dollar, having fallen more than 15 cents since June.

But signs are that banks will be at the sharp end of the crisis. Accounting for around half of outstanding Russian corporate Eurobonds, according to Commerzbank estimates, banks are facing a rise in bad loans at home due to economic recession and this year's sharp rise in interest rates.

Bonds from big state-run lenders Sberbank, VEB and Russian Agricultural Bank are down five-10 cents since June.

Capitalization levels for Russian banks are already thin, Morgan Stanley analysts warn, estimating a buffer of just $25 billion for the top 50 banks.

"Any further squeeze on profitability, if it materializes, will likely result in a serious credit crunch next year, in our view," they added.

There is another category — companies such as Sistema or Brunswick Rail, whose bonds have already plunged to 50-60 cents in the dollar due to their own troubles with the government or because of the economy's woes.

Brunswick, a railcar leasing company, said this week that it was "preparing for the worst situations," as the economic crisis cuts into rail and rail freight use, Thomson Reuters news service IFR reported

In fact, with growth likely flatlining for years. "fundamentals may soon overtake geopolitical risk premium as the key concern for Russian corporates," reckon JPMorgan analysts, who advise clients to stay underweight in the sector.

Meanwhile analysts' eyes are trained not on 2015 but the year after, when another $85 billion or so fall due. The key factor is whether sanctions are lifted, says Commerzbank strategist Apostolos Bantis.

"We are not in a restructuring situation yet," he said. "But if by next summer all these pressures are still there, it will be time to start thinking of debt restructuring risks."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.