For reasons that are understandable even to an arch-realist such as myself, increasingly large numbers of Europeans — including many people in countries that have traditionally been quite sympathetic to Russian concerns — have decided that Putin's Russia is not a "partner" to be engaged with, but an adversary to be confronted, isolated and eventually defeated.

While growing, the membership of the European Union's "hawkish" bloc is a bit of a moving target. A few years ago it would have clearly included both the Czech Republic and Slovakia, and while it would be a gross exaggeration to call either country's current government "pro-Putin" there has been a noteworthy shift away from their more confrontational past positions. Hungary, too, has seen its government soften the rhetoric it aims at Moscow.

The core group of Russia hawks, which includes Poland, Britain, Sweden, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, has not only become increasingly outspoken about the Russian threat, but has had real success in pulling formerly reluctant countries like Germany and France closer to its preferred approach.

The EU's approach might not have been entirely hawkish in orientation — given the time-consuming and inefficient way in which EU policy is created, this was never a possible outcome — but it is a lot tougher than many people, including Russian President Vladimir Putin, expected when the situation in Ukraine first started to go haywire.

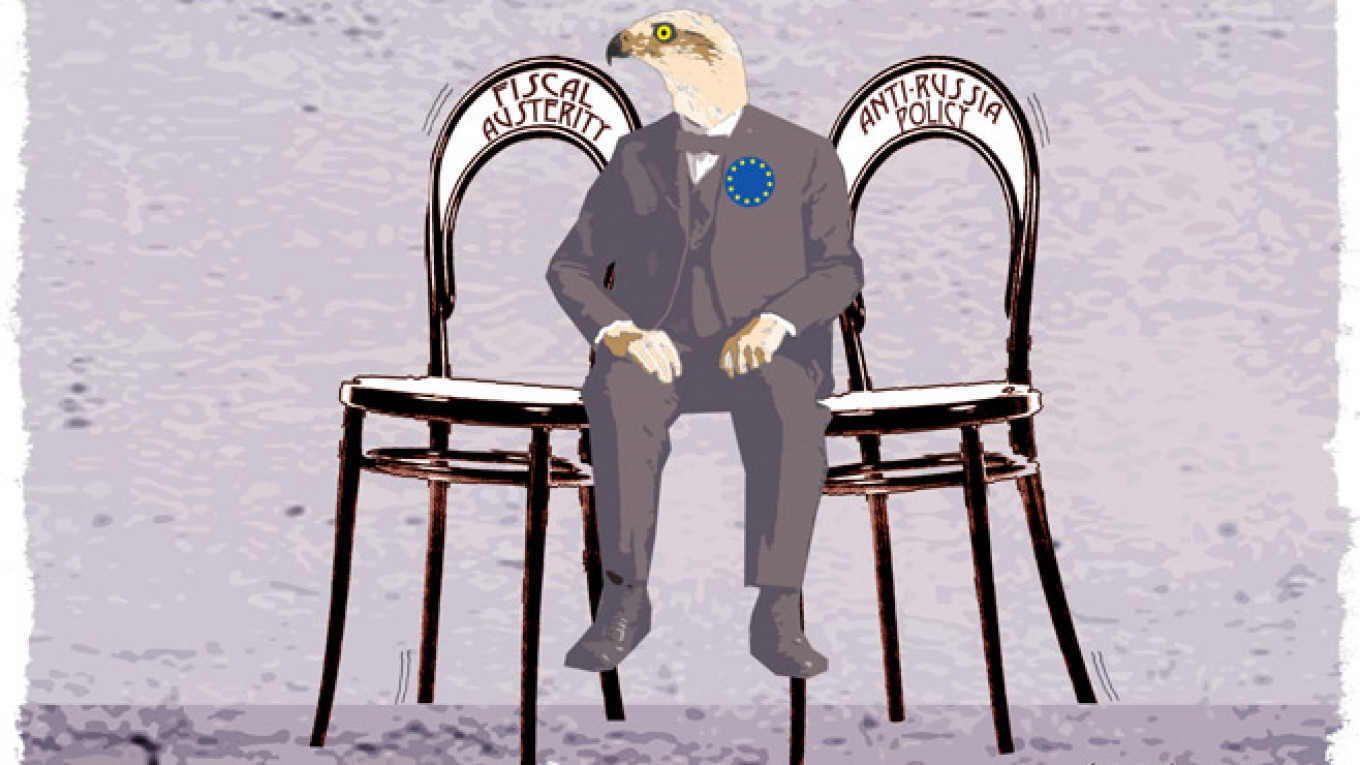

For various reasons, most of the members of the core group of Russia hawks are also part of what, for lack of a better phrase, could be called the "monetary hawks." While they are not identical in their economic policies, monetary hawks are generally of the opinion that the best way out of the current slump is "structural reform" combined with sharp reductions in government spending.

Germany — rather moderate in terms of its foreign policy — is a loud and active member of the group, and has succeeded to a quite remarkable degree in enforcing an EU-wide policy of fiscal austerity.

The problem that is becoming ever clearer is that the two groups of hawks are advocating policies that are mutually exclusive. While in the past a confrontational Russia policy and an austere economic policy might have been possible at the same time, this is no longer the case.

In order for the EU to follow a Russia policy that would actually weaken the Kremlin's position in Ukraine and other countries in the region, it will have to spend enormous amounts of money. At an absolute minimum, maintaining the current — rather modest — level of economic sanctions will cost Europe billions of dollars.

Other proposals favored by the Russia hawks, such as creating an EU-run "rapid reaction force" capable of thwarting any potential Russian military incursion or buying the Mistral warships from France to prevent their transfer to the Russian navy, will cost several billion more.

The direct costs of a more aggressive Russia policy, while not insubstantial, are absolutely paltry in comparison with the costs of bailing out Ukraine — a necessary precondition for weakening Moscow's power within its self-declared "sphere of influence." Precise estimates differ significantly from economist to economist, but the damage to Ukraine's economy has already been so severe that the minimum cost of a bailout is calculated in the tens of billions of dollars.

Other policies that have been publicly advocated by the hawks, such as a modern "Marshall Plan" that would jump-start Ukraine's economy through massive infrastructure investments, would cost tens of billions of additional dollars. In the EU's current environment of budget cuts, unemployment and economic malaise, that is real money.

I won't pretend that I favor such a foreign policy approach, but many intelligent and capable people do. The problem for the Russia hawks is that the monetary hawks (who are often the very same people) have very loudly and very insistently repeated the claim that the EU is effectively broke and that there is an urgent need for governments across the continent to get spending under control.

I don't want to get bogged down in a stimulus-versus-austerity debate, but what does seem clear is that it is politically impossible to argue that the EU needs to radically cut government spending while simultaneously spending tens of billions of taxpayer dollars bailing out Ukraine so that it can stand up to Russia.

The idea that the EU takes from Peter to pay Paul — that it is taking "hard-earned" money away from people to pay shiftless foreigners — is precisely what has caused such an explosion of Euroskeptic parties like the U.K. Independence Party. By advocating both fiscal austerity and an aggressive — and extremely expensive — foreign policy, the hawks have left themselves extremely vulnerable to populist challengers.

So what is to be done? Hawkish political parties and politicians need to do some very hard thinking about what they value more highly. Do they want to see fiscal restraint and an effort to trim bloated public sectors? Or do they want to see an emboldened and aggressive EU force Putin to back down?

They are going to have to decide, as the continent's economy is in far too parlous a condition to allow both policies to be pursued at the same time. Hawks are in a strong enough position that they could prevail on either issue, but not on both.

What I imagine will happen is that the Russia hawks will hold their noses and acquiesce to a slightly more Keynesian approach to the euro zone's economic crisis. This compromise is the only realistic way to convince highly skeptical countries in Southern Europe that they should go along with a more interventionist approach to the crisis in Ukraine.

Without some kind of compromise, however, the EU will continue to march on as fecklessly as it has in the past, writing rhetorical checks it has no practical ability to cash.

Mark Adomanis is an MA/MBA candidate at the University of Pennsylvania's Lauder Institute.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.