Russia can do little to shore up slumping oil prices — even if OPEC wants it to — as its wells will freeze if they stop pumping oil, and the country has no capacity to store the output it would otherwise export, analysts say.

Before next week's meeting of OPEC, Russia has already spoken to group member Venezuela about the need to "coordinate actions in defense" of oil prices and it plans to send a high-ranking delegation to press the message.

But despite needing oil prices of $100 a barrel to balance its budget, Russia has changed little since 2008 when the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries urged Moscow to join forces to cut supply to shore up prices.

Then and now, the world's biggest producer lacks the ability to increase or turn down its own production.

"Nothing has changed," said Valery Nesterov, an analyst with Sberbank CIB, adding that while China has built storage to beef up its stocks for its energy-intensive economy, Russia has constructed no new facilities.

Nesterov also said Russia had a harsh climate and challenging geology, which meant it cannot simply stop wells from pumping oil. "Russian wells will just freeze if you stop them."

But that does not mean that Moscow will not try to persuade others to help shore up a price, which has fallen 33 percent since June to $78 a barrel.

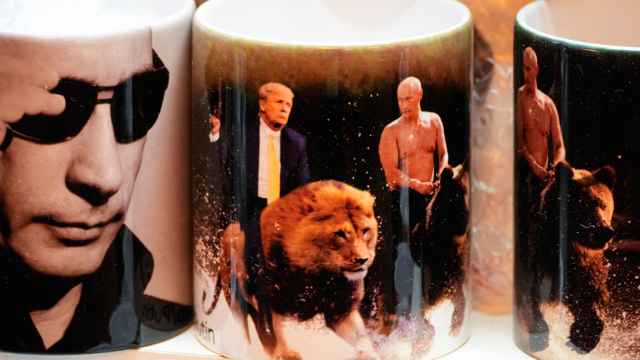

Igor Sechin, chief executive officer of Russia's biggest oil producer Rosneft and a long-standing ally of President Vladimir Putin, and Energy Minister Alexander Novak will both fly to Austria days before OPEC is due to meet in Vienna.

They are due to attend a conference with Venezuelan officials, but have not shed light on the agenda or the other participants. Novak's spokeswoman said Thursday that the minister would not attend the OPEC meeting itself.

Oil market watchers are divided on the outcome of the meeting in Vienna, which will be the most uncertain for years. Analysts are split over whether there will be a coordinated cut, with some saying output could be reduced by up to 1.5 million barrels per day (bpd).

Only Revolution Will Help

Some experts argue that Russia could even need oil prices as high as $115 to balance the budget, since social and military spending have soared, while Western sanctions over Ukraine have cut off Moscow from funds it borrows in Western financial markets.

Given that its production cannot be stopped, the only option left would be for Russia to cut its exports, which stand at about 4 million bpd.

Asked whether Russia could hold back oil it would normally export, a trader at a major western oil company said: "And where would you put it?"

Some oil could be stored in the Transneft pipeline system, one of the world's longest, he said. But it was never supposed to be used for prolonged storage, as it is reserve capacity to be used only in the event of if technical problems.

Transneft did not respond to a request for comment.

Russia's only major oil storage facility, the floating storage vessel Belokamenka located in the Barents Sea, can hold 2.6 million barrels.

An industry source said that even though Belokamenka is not full at the moment "you will need 365 like it to take off 2 million bpd from the market."

The position is different with Saudi Arabia, OPEC's leading producer. Unlike in Russia, where about a half of oil production is in private hands, Saudi Arabia controls all of its output via state-owned Saudi Aramco.

The company has a large fleet of supertankers that can be used to store oil at sea and also owns or leases oil storage facilities around the world.

Russia sells a big chunk of its oil to trading houses and oil majors, thus leaving the decisions where and how to store crude to its buyers.

Mikhail Krutikhin, a partner with the RusEnergy consultancy, said Russia could not influence oil prices through export cuts and joked that more drastic measures might be needed.

"There is no real way for Russia to support prices, only to make a revolution [in] some oil producing country," he said.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.