There were some fears voiced that this show would never make it to Russia. As relations between Russia and Britain have worsened this year and the U.K.-Russia year of culture looks to some like an idea of hopeless optimism, an exhibit about Oscar Wilde, the witty Irish writer behind plays like "Lady Windermere's Fan," and Aubrey Beardsley, the genius and deliciously decadent illustrator, would seem the first thing to go out the window.

But "Oscar Wilde. Aubrey Beardsley. A Russia Perspective," now on at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, is proving popular and a great reminder of how the two countries' cultural relations go so far back.

"The exhibition gives evidence of how inspiring these two key figures of the British aesthetic movement were for the poets, artists, theater producers, actors and, of course, the public in Russia," said one of the exhibition's curators, Zinaida Bonami. "It was really a dialogue. And I dare say, it still remains a dialogue with all those who are fond of British art."

The exhibition tells the narrative of how "art for art's sake" shaped the lives and works of those like Wilde and Beardsley, who chose beauty as their religion and freedom of self-expression as their credo.

A total of 150 artworks are on show, on loan from the Tate, the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum and the National Portrait Gallery. Among the works on show are Beardsley's illustrations for Wilde's scandalous play "Salome" and for Aristophanes "Lysistrata," a work that Beardsley asked to be destroyed ("by all that is holy, all obscene drawings") a year before his death in 1898 at the young age of 25.

Pointing at the success of the pre-Raphaelites's show last year at the Pushkin, Bonami said that Wilde and Beardsley are part of the period in British art that has always drawn admirers and eventually led to modernism.

Wilde was widely published in Russian and he was so popular that his fans were often called a cult. It was not only his writing style that was his copied but his manners too.

"Wilde and Beardsley were specially admired by the Russian Silver Age," Bonami said, referring to writers from the last decade of the 19th century and the first two or three of the 20th century. "We can definitely say that in the early 20th century, they both were icons for Russia."

Writers who were fans included Valery Bryusov, Andrei Bely, Maximilian Voloshin and Nikolai Gumilev, a number of whom became Wilde's translators. His play "Salome," which was published in Britain with illustrations by Beardsley but could only be staged in Paris, inspired several attempts to stage it in Russia though a number of productions were stopped because of state censorship.

Beardsley, primarily a book illustrator, had a brief but bright career creating a unique artistic language that spread across Europe and conquered Russia at the turn of the 20th century. Like Wilde, his appearance was important, and his dandyish style spread to Russia too, producing, according to Kommersant critic Yekaterina Istomina, an "army of pale youths with painted lips and black greased hair."

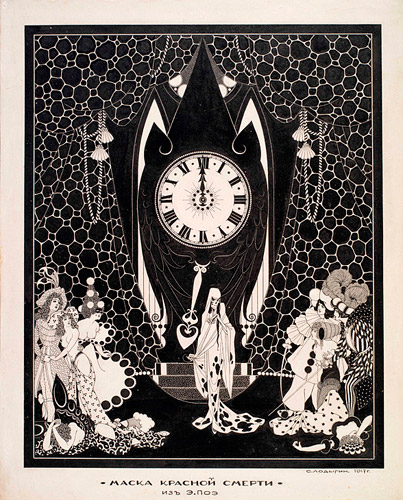

A piece by Sergei Lodygin, who was greatly influenced by Beardsley.

His style, which relies on a flat spatial plane and sharp black-and-white lines, often features grotesque figures and expressive sensuality and was called decadent by critics.

He had his hand in many of the art quarterlies of the era, but it was one, "Yellow Book," which owed its signature designs to Beardsley, that ended in scandal after the media erroneously reported that Wilde was carrying a copy of "Yellow Book" while on his way to his trial for gross indecency, as homosexual acts were defined then. The subsequent scandal cost Beardsley his job.

After the scandal, Beardsley was only commissioned for books "on risky subjects." His bold, some would say pornographic, illustrations for Juvenal's "Satires" and Aristopanes' frivolous comedy "Lysistrata" are probably among his most controversial drawings. He died of tuberculosis at the age of 25.

"Beardsley and his black-and-white manner of drawing gave birth to a special trend in Russian graphics, to say nothing about his influence upon the image of numerous Russian art magazines, such as Apollon, Zolotoye Runo and Mir Isskustva," Bonami said.

The exhibition is the first time Beardsley is represented together with his Russian followers. Graphics by Russian artists Konstantin Somov, Sergei Lodygin and others are on show including the so-called "Moscow Beardsley" Nikolai Feofilaktov.

"I did not know anything about Aubrey Beardsley before this exhibition. The refined manner and impressive detail of his graphics are really striking, as well as the boldness of his illustrations for Aristophanes' 'Lysistrata,'" said one exhibit visitor, Pyotr Korolev.

"Shortly before his death, Oscar Wilde mentioned that he would hardly get new friends in his life, but possibly some after his death," Bonami said. "I happened to be at his grave at Pere Lachaise [Cemetery] in Paris this month and was really amazed by his popularity today."

His and Beardsley's popularity is likely to increase in Russia after this exhibit.

"Oscar Wilde. Aubrey Beardsley. A Russia Perspective" runs till Nov. 16. Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. New Western Art Gallery. 14 Ulitsa Volkhonka. Metro Kropotkinskaya. 495-697-1546.

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.