It became clear just how much the subject of NATO is a sore spot for Russian society when new NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg was quoted in a recent interview on Polish television as saying that NATO would base its forces "wherever we want."

Moscow immediately responded by reminding the West that such a policy would violate agreements between NATO and Russia — prompting Brussels to hurriedly issue a correction, claiming that the Polish translator had misquoted Stoltenberg.

Of course, mistakes happen, but considering that Russian-Polish relations have been far from ideal for centuries, it is entirely possible that the translator heard exactly what Warsaw wanted to hear.

Nor does Moscow's frustrated and angry response come as any surprise: Russia is convinced that the West broke its promise that NATO would refrain from expanding into Eastern Europe in exchange for the reunification of Germany. True, that pledge was never set down in a legally binding document, but the feeling remains that Russia was betrayed.

The Russian mentality also plays a role here because legal documents do not hold the same sway in this country as they do in the West. Even with all the corruption that exists, a solemn promise carries more weight for many Russians than does a notarized document.

And finally, it is clear why Brussels rushed to issue the correction: Relations have already deteriorated into a new Cold War without adding this problem as well.

And yet, the situation is a double edged sword: It helps NATO find a new purpose following the collapse of the Soviet Union, and it provides justification for a Russian military buildup. But other than the military-industrial complexes of both sides, who really stands to gain from a new arms race?

Obviously, Russian politicians, generals and admirals take whatever stance toward NATO their jobs demand.

Every general staff in the world constantly updates its plans with regard to potential opponents — and Russia and NATO do the same with regard to each other, regardless of the peace-loving speeches made by their respective diplomats and political leaders.

And yet that does not preclude Russia partnering with the West on issues where their interests coincide. This relationship will continue for the foreseeable future, with only the degree of confrontation or cooperation varying according to circumstances.

Of greater interest is the attitude the average Russian holds toward NATO. Even before the current strained relations, the fact that NATO expanded ever closer to Russia's borders, bombed Yugoslavia and brought the former Warsaw Pact states into its fold had irritated Russians.

Now with Western sanctions in place, it is fair to assume that anti-NATO sentiments have only intensified.

On the other hand, if you dig a little deeper, it turns out that very few Russians actually fear NATO. Others see it as a potential though not imminent threat, while many others are simply indifferent to the alliance. There are at least three reasons for such "fearlessness."

First, Russia's nuclear capability remains its primary security guarantee. Second, today's Russians, brought up studying the history of World War II, find it difficult to view the "fighting brotherhood" of the Dutch, Icelanders, Estonians and so on as a threat.

They see that whole motley contingent as not only unfit for battle, but also as an encumbrance that only deprives maneuverability to the U.S. and major European countries.

What's more, Russians question the effectiveness of NATO's best-trained forces, knowing that they have only fought against much weaker opponents in recent decades.

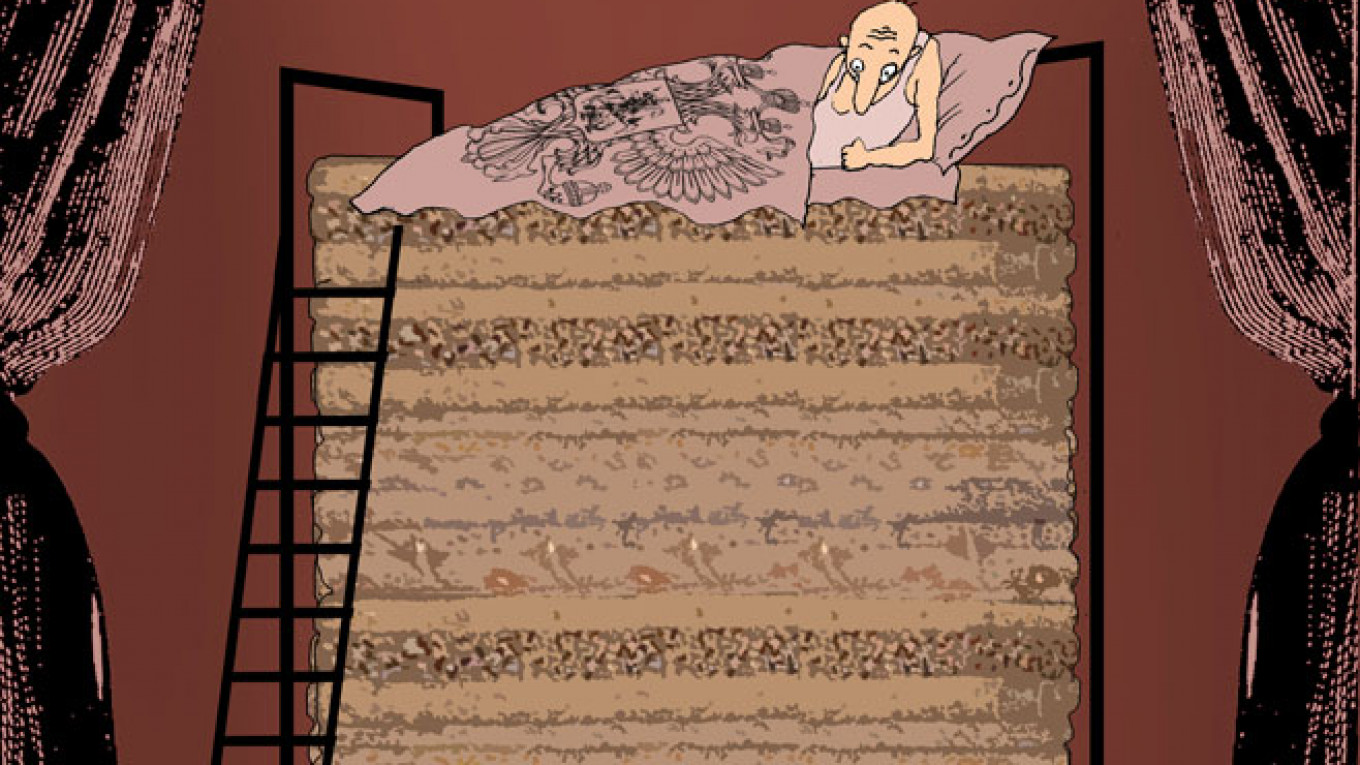

Third and finally, the average Russian takes comfort in knowing that, while former President Boris Yeltsin allowed the army to fall into disarray, President Vladimir Putin has slowly but steadily rebuilt the country's armed forces.

Also, in place of the somewhat doubtful former Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov, Russia now has a more experienced organizer in current Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu.

Of course, the armed forces alone do not guarantee a country's peace and security. But truth be told, most Russians do not devote a great deal of serious thought to the pros and cons of the president's policy.

But to the chagrin of the West and the domestic opposition, those who do think about it tend to conclude that they are satisfied with Putin on the whole — that is, at least for now.

Pyotr Romanov is a journalist and historian.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.