Yury Lyubimov once told me about meeting the great director Vsevolod Meyerhold. This happened in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1987. I paid Lyubimov a visit to talk about his old friend, the playwright Nikolai Erdman, but the conversation, naturally and fortunately, took plenty of detours.

The story in Lyubimov's words went like this: "Meyerhold came to watch us at the Vakhtangov [theater school] and he was taken with the way I was doing pantomime. Ruben Simonov, the theater's director at the time, called me over to introduce me to him. Meyerhold said to me, 'Never forget about movement. It is a great thing, young man. The body is as expressive as the word. Train yourself. Spend your whole life in training.' And that is what I have done."

I asked Lyubimov, who made history as the founder of the Taganka Theater, if he said anything in return. His reply came quickly. "Nothing," he said. "I merely listened to a great master. And I was happy that I had been introduced to him."

I couldn't help but remember this exchange when, last week, I stood with hundreds of Muscovites and watched as Yury Lyubimov's casket was lowered into a hole in the ground and covered with damp, red clay at the Donskoye cemetery. Lyubimov, who died on Oct. 5 at age 97, was buried in a plot belonging to his family.

I have made many trips to the Donskoye cemetery over the years. In fact, I had walked past the Lyubimov family plot many times, not knowing it was there. The reason for that is because Nikolai Erdman, whom, along with Vladimir Mayakovsky, we might rightly call Meyerhold's favorite playwright, is buried in his own family plot perhaps 30 yards away. From time to time I stop by to pay respects to the writer who inspired me long ago to write my first book.

What a coincidence: Lyubimov and Erdman, who first met during World War II in the incongruously named NKVD Song and Dance Ensemble, and who remained close friends until Erdman's death in 1970, would end up in the same cemetery a stone's throw from each other.

But that's only part of this story because on the other side of the cemetery there stands a marble slab with the following words carved into it: "Common Grave No. 1. Disposal Place of Unclaimed Ashes From 1930 to 1942 Inclusive."

Just to drag the tale out a bit, allow me to add that a larger slab stands right behind the main one. On it are engraved the words: "Here are deposited the remains of innocently martyred and executed victims of political repression, 1930-1942. Eternal memory to them."

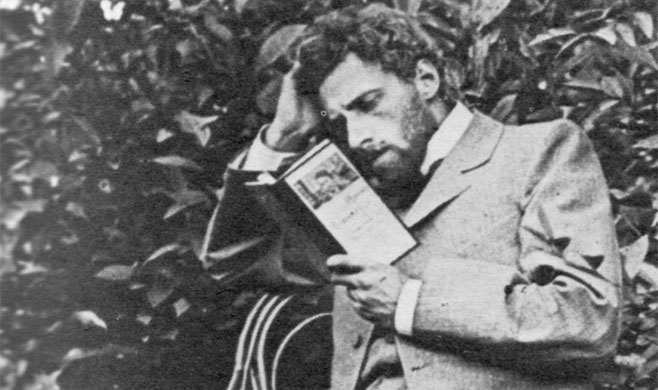

Meyerhold preparing for a Moscow staging of "The Seagull" in 1898.

Yes, if you have brushed up on your history dates you may recall that Vsevolod Meyerhold was shot, probably in a basement in the Lubyanka secret police headquarters, on Feb. 2, 1940, one week before he would have turned 66. And, yes, that means that, in all likelihood, this plot of ground is the final resting place of one of the greatest, most influential avant-garde artists Russia ever produced.

It is a maddening little piece of earth. No one knows how many hundreds, perhaps thousands, of individuals were dumped here. All we see now is a small hexagon bordered in cement and utterly groaning under the weight of small signs bearing the names and dates of victims whose ashes were tossed into a pit with no thoughts whatsoever.

Let me repeat that — "with no thoughts whatsoever."

That rhetorical sawhorse, "What were they thinking?" does not apply here. Those having anything to do with these "innocently martyred and executed victims of political repression" were not thinking — at all.

To this day no sign commemorates Meyerhold's presence at the Donskoye cemetery. He remains an anonymous victim, such a contrast to the worldwide fame he enjoyed during his life.

And so it happens that Vsevolod Meyerhold, his playwright Nikolai Erdman, and, perhaps, his finest disciple, Yury Lyubimov, are now all buried together in the same earth.

Meyerhold, the first to arrive, was dumped unceremoniously into a pit. Erdman, the next, was buried by a tiny group of close friends. By the time he died he had been "forgotten" for nearly 40 years.

Lyubimov, in a turn of events that seems perfect in its synchronicity, has now joined them. He was buried with great pomp, ceremony and deserving respect.

Three greats. Three very different lives and deaths. All now equal in the eyes of history.

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.