Russia's budget is in a bind, as slowing economic growth and Western sanctions over the crisis in Ukraine turn the spending promises of yesterday into tomorrow's liability.

Last week, the government submitted its budget proposal for the next three years to the State Duma, sparking controversy with a plan that relies on the optimistic oil price of $100 per barrel and increases defense purchases at the cost of health care and education.

But if Russia were to put a priority on economic growth, what should it spend on and, perhaps more importantly, what expenses should it cut? With this is mind, we asked economists what they would do if given the chance to rewrite Russia's budget.

What to Cut:

1. Military Spending

One of the most controversial points of the proposed budget is a continued increase in defense spending. Russia's military budget has climbed steadily since 2011, rising by more than 1 percent of GDP over that period, said Alexander Deryugin, director of the Center for Regional Reform Studies at the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration.

The surge in military spending is predicated on the state's massive $700 billion rearmament program through 2020, which has only climbed on Russia's list of priorities amid collapsing relations with the West over the war in eastern Ukraine.

There is a plus side to the increase, though: State military purchases are now the sole engine of growth in manufacturing. About 1.3 percent of the 1.4 percent growth in manufacturing seen this year is the direct or indirect result of military purchases, according to a recent study from the Higher School of Economics.

Nonetheless, a balanced budget demands that the costly rearmament plans be spaced out over a significantly longer period of time, Deryugin said.

2. Public Sector Salaries

With his return to power in 2012, President Vladimir Putin signed a sweeping series of presidential orders known as the "May decrees," which pledged to provide hefty annual salary increases for state employees.

The reforms have undoubtedly been popular among public sector workers, Putin's main electorate. And since public sector workers accounted for 25.7 percent of Russians who were employed or actively seeking employment last year, according to the State Statistics Services, higher salaries for these citizens could help increase spending and, hence, economic growth.

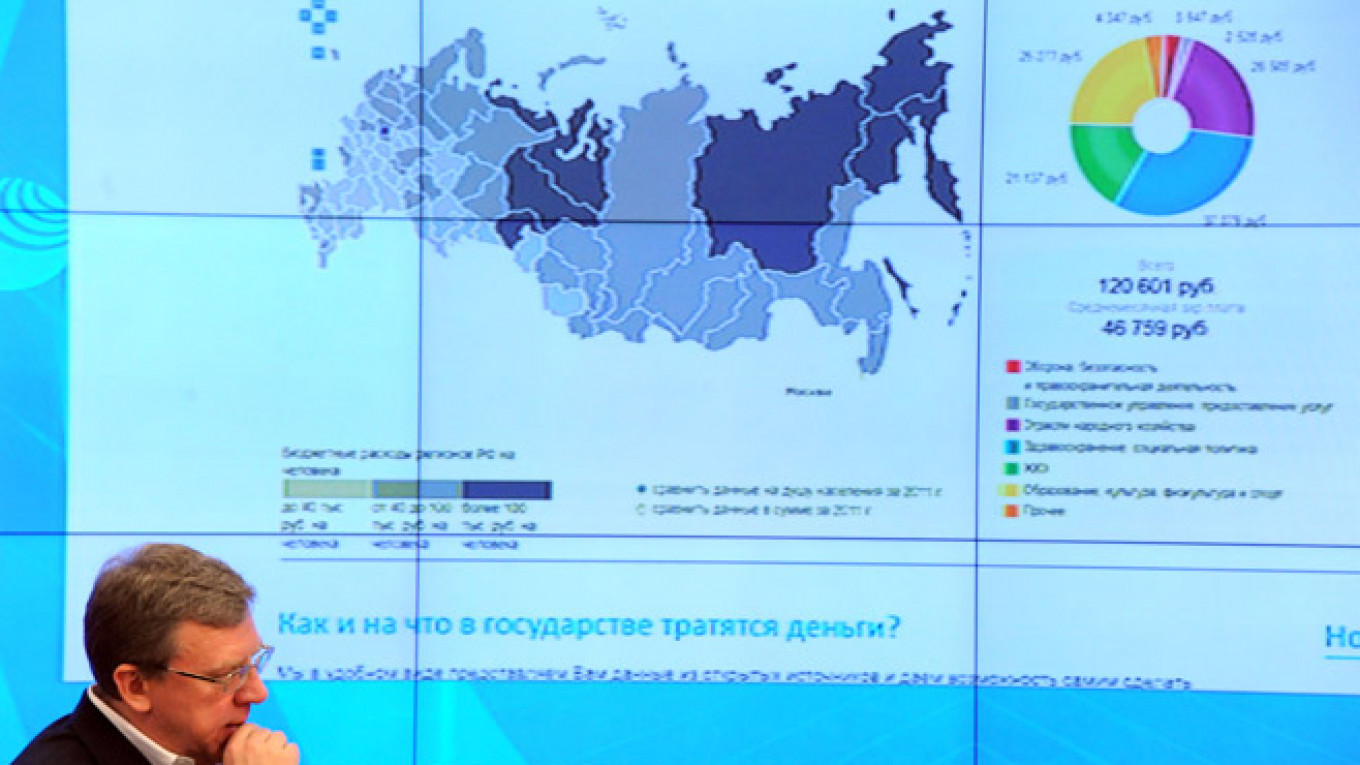

But as tax revenues fell over the past year, these decrees have wreaked havoc with the budgets of regional governments.

Traditionally more balanced than the federal budget, only six of Russia's 83 regions managed to avoid a deficit last year, Deryugin said.

"The decrees were adopted under different economic conditions, and now the situation has changed drastically for the worse. … The budget will not survive this," Deryugin said.

Well aware of the problem, the government has asked that the rate of salary increases be slowed to 5.5 percent next year, or the anticipated level of inflation, news agency RBC cited Finance Minister Anton Siluanov as saying.

Without these changes, the government would be obliged to raise state employees' salaries by between 10 and 15 percent every year.

Where to Spend

1. Infrastructure

All analysts polled by The Moscow Times agreed that for long-term economic growth, the government needs to spend more on Russia's infrastructure — from "soft" infrastructure, such as health care and education, to "hard" infrastructure, including highways, railways and electrical grids.

Poor physical infrastructure is widely seen as a roadblock to investment in Russia. Fledgling agricultural enterprises, for example, are weighed down by the high costs of connecting to electrical, plumbing and transport grids, while e-commerce — one of the country's fastest-growing sectors — finds its expansion into Russia's countryside limited by less-than-optimal roads and a poor public postal service.

Education and health care are also in need of a radical overhaul. Industries ranging from metallurgy to advertising all suffer from a lack of qualified specialists, the unhappy marriage of a demographic slump and an outdated education system that fails to prepare students for the modern workplace.

Russia is already investing in some infrastructure projects, most notably in the construction of stadiums, roads and other modes of transportation leading up to the 2018 FIFA World Cup. Still, the scope of the state's infrastructure investments will need to be considerably widened and targeted to the needs of business in order to achieve long-term results.

2. Manufacturing

The Russian economy has risen and fallen over the past decade largely on the price of one commodity: oil. High prices meant prosperity, and a fall to $38 per barrel following the 2008 financial crisis sent Russia's currency and GDP plummeting.

Now, with the price of oil below $95 to a barrel and the United States steadily increasing oil production, Russia is looking to a future where that reliance could well become a liability.

State support for manufacturing is one crucial way for a resource-based economy, such as Russia's, to insulate itself from these price fluctuations and spur economic growth, said Valery Mironov, chief economist at the Higher School of Economics' Center for Development.

Support must be administered with extreme caution, however, as the money funneled into government programs could simply disappear due to corruption and institutional inefficiency.

"You need the kind of support and government programs that can't be stolen," Mironov said. Currency devaluation, cutting the processing times for construction permits and setting lower prices on the services of natural monopolies, such as railroads and public utility companies, are all possible mechanisms for supporting business.

In this way, the more than 20 percent devaluation of the ruble against the dollar this year could in the long term be a boon for Russian manufacturing, as the price of imports grows and cheaper Russian-produced goods gain a relative competitive advantage.

But new manufacturing enterprises first require investment, which is increasingly hard to come by in Russia, where Western sanctions have cut off state-owned banks from EU and U.S. capital markets, thereby raising the cost of lending across the board.

The uncertainty in the political climate has to end first, Mironov said, and then — hopefully — growth will follow.

Spending on infrastructure and trimming state spending is, of course, only half of the story. As any economist will tell you, Russia's economic future will have less to do with government spending than with renewing the influx of investment.

"[Improving Russia's economic growth] is still about recovery of private capital spending, which requires better investment climate and further ease-of-doing-business reforms," said Oleg Kuzmin, chief economist for Russia and the CIS at Renaissance Capital. Until investors are once again ready to do business in Russia, tinkering with the state budget can only ease Russia's path toward a healthier economy.

Contact the author at d.damora@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.